Joining the U.S. Army has always been a bold expression of service, but that dedication hasn’t always been met with equal pay. Throughout American history, soldiers have often received lower wages than their civilian counterparts, even while facing extreme conditions, long separations from home, and life-threatening missions. From the Continental Army’s early struggles to the modern professional force, compensation has frequently failed to reflect the full cost of military life. In this article, we’ll explore how military pay has evolved—and why debates over fair wages for service members continue to this day.

Revolutionary War

The Revolutionary War was a battle for independence between the United States and Britain. During the war, the Continental Army consisted of about 150,000 men, though only 17,000 were actively serving at any given time.

Soldiers were paid based on their rank. Enlisted men were promised a one-time bonus, either in land or money, along with a monthly wage. Privates earned $6.00 per month, while generals were paid $8.00. Captains received $20.00, and colonels made $50.00 per month. However, due to rising inflation, these wages quickly lost their value, and the Continental Congress was slow to adjust them.

After some negotiations, certain ranks received pay raises. Colonels’ salaries increased to $75.00 per month, and captains’ pay doubled to $40.00. Unfortunately, privates saw no increase, leaving them struggling financially since they had to buy their own uniforms, weapons and gear.

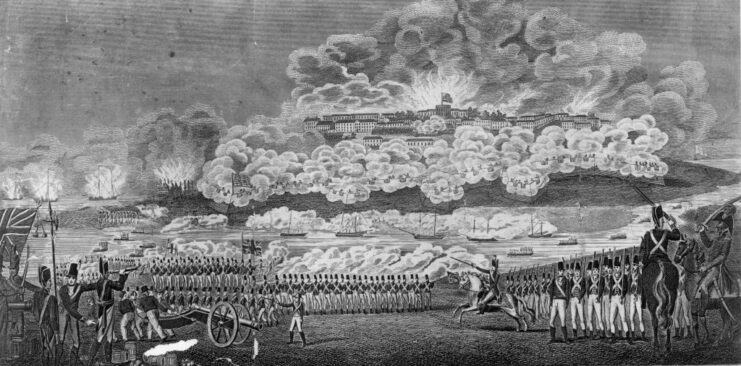

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, enlistment terms were initially set at five years, but the government soon extended service requirements to cover the entire duration of the conflict. To attract more volunteers, the Army offered a signing bonus starting at $31 along with 160 acres of land. This incentive later doubled to $124 and 320 acres—exceeding the annual earnings of most workers at the time.

Privates began with a monthly pay of $5, while sergeants and other non-commissioned officers earned between $7 and $9. Officers received significantly higher wages, ranging from $20 up to $200 per month. Due to recruitment challenges, the government eventually increased pay for privates and non-officers by an extra $4 each month.

One of the biggest issues early on was the slow distribution of pay. Soldiers frequently faced long delays, sometimes waiting months before receiving their wages. This caused unrest, including refusals to march and even mutinies in October 1812. By late 1814, many were still owed six to twelve months of back pay.

Mexican-American War

During the Mexican-American War, the U.S. Regular Army was composed of specialized branches such as infantry, cavalry, artillery, and engineers. At the war’s outset, the active force was modest in size—only 7,365 troops—most of whom served within eight infantry regiments.

Enlistment terms lasted five years, with soldiers earning roughly $7.00 per month. Because of the meager pay, the army primarily attracted men with limited employment prospects or formal education. A significant number were immigrants—by 1845, around 42% of the force was foreign-born, with the majority being Irish and the rest hailing from various European nations.

To bolster troop numbers during wartime, the federal government could request volunteer regiments under the Militia Act of 1792. While these volunteers were obligated to serve wherever the War Department directed, official state militias could not be deployed beyond their own state lines without consent.

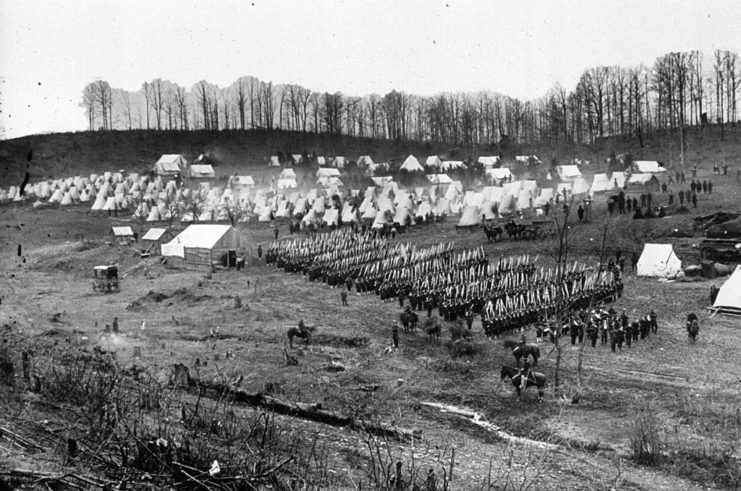

American Civil War

Troops’ salaries between the Confederate and Union armies during the American Civil War differed:

- Privates – $11.00 (Confederacy) vs. $13.00 (Union)

- Corporals – Both received $13.00

- Sergeants – Both received $17.00

- First Sergeants – Both received $20.00

- Quartermaster Sergeants and Sergeant Majors – Both earned $21.00

- Second Lieutenant – $80.00 (Confederacy) vs. $105.50 (Union)

- First Lieutenant – $90.00 (Confederacy) vs. $105.50 (Union)

- Captain – $130.00 (Confederacy) vs. $115.50 (Union)

- Major – $150.00 (Confederacy) vs. $169.00 (Union)

- Lieutenant Colonel – $170.00 (Confederacy) vs. $181.00 (Union)

- Colonel – $195.00 (Confederacy) vs. $212.00 (Union)

- Brigadier General – $301.00 (Confederacy) vs. $315.00 (Union)

- Major General – $301.00 (Confederacy) vs. $457.00 (Union)

- Lieutenant General – $301.00 (Confederacy) vs. $748.00 (Union)

- General – $301.00 (Confederacy)

Officer pay for both sides included allowances, which the salaries of Confederate generals didn’t reflect. As well, all Confederate generals received the same base pay, as regulations recognized just one grade above the rank of colonel. However, generals holding different commands were afforded additional allowances, and those commanding in the field received an additional $100.00.

US Colored Troops were paid a meager salary of $10.00 a month for the majority of the war, of which $3.00 was deducted for clothing allowances. While soldiers on both sides were meant to be paid every two months, this rarely happened, due to the great distances the military paymaster had to travel.

Spanish-American War

The Spanish-American War saw the end of Spanish colonial rule in America and allowed the US to acquire territories in Latin America and the western Pacific. During the conflict, Army privates were paid a monthly salary of $13.00, the same as during the Civil War. However, unlike in previous years, its value was higher, due to deflation.

According to a newspaper article published in the Rome-News Tribune on February 17, 1980, one private’s pay was eventually increased to a “whopping” $30.00 a month, a massive increase for those used to being paid just a third of that amount.

World War I

World War I was a brutal conflict, featuring trench warfare, bloody battles and the introduction of poison gas. Troops serving in Europe received varied salaries based on the number of years they’d been enlisted. For example, a private in their first year of service earned $30.00 a month, while corporals received a salary of $36.00.

A full list of pay for each section of the Army, as well as the salary increases for each year of service, can be found here.

On top of their monthly salaries, troops were also provided life insurance through the War Risk Insurance Program. This was due to commercial insurance companies either charging higher premiums for soldiers or excluding protection against the hazards of war.

World War II

Prior to World War II, serving in the military wasn’t everyone’s first choice in career. In 1939, the Army featured a roster of 189,839 servicemen. That changed following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and by 1945 there were 8,267,958 enlisted.

Salaries vary depending on the source. According to Moneywise, privates were paid $21.00 prior to the US entering the war, a total that increased to $50 in September 1942. The National WWII Museum, on the other hand, lists the average base pay for enlisted servicemen at $71.33, with officers earning a salary of $203.50.

WWII also saw the introduction of Badge Pay for combat infantry members, due to the hazardous conditions they fought in. The initiative awarded $10.00 a month to holders of the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, earned through combat service, while those with the Expert Infantryman’s Badge, earned through proficiency training, were given $5.00.

Korean War

The Korean War erupted when 75,000 troops from the North Korean People’s Army crossed the 38th parallel, the boundary separating them from the Republic of Korea. This invasion sparked three years of intense conflict.

As in previous wars, monthly salaries for troops were based on rank and length of service. For instance, in 1952, an E-1 with under four months of service earned $78.00 per month, while an E-7 received $206.39. Additional allowances such as Aviation Pay, Submarine Duty Pay, and Sea and Foreign Duty Pay could further influence these amounts.

That same year, Combat Pay was introduced as the first modern example of direct compensation for combat. This pay offered $45.00 per month to those serving at least six days in designated “combat units” or to those wounded, killed, or injured by enemy action.

Vietnam War

E-1 wages remained the same between 1952 and ’58, meaning troops among the Army’s lower ranks made the same salary in both the Korean and Vietnam wars. However, when inflation was factored in, those serving in Vietnam were actually earning less.

As the conflict progressed, new troops were given a salary of $78.00, while those who’d served over four months earned $83.20.

In 1963, Combat Pay was renamed Hostile Fire Pay (HFP) and remained relatively the same. The only difference was that the Department of Defense was granted near-complete discretion over how it was administered, leading to multiple changes. This included the rescinding of the six-day criterion and the introduction of “zonal eligibility.”

Gulf War

In August 1990, Saddam Hussein ordered his forces to invade Kuwait. Other Middle Eastern countries called for the US and the United Nations to intervene, and the UN’s Security Council set a deadline for him to withdraw forces by the middle of January 1991. When he failed to do this, the US launched Operation Desert Storm.

According to Business Insider, those serving in Iraq with over four months of experience were making $753.90 a month, while those with less than that earned around $697.20. They were also eligible for Hostile Fire Pay/Imminent Danger Pay.

Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq

The US began the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003, respectively. With the War in Iraq, deployed troops were making just a few hundred dollars more than those who’d served in the Gulf War. Veterans earned a monthly salary of $1,150.80 and those with less than four months under their belt took home just $1,064.70.

More from us: 5 Of The Most Brutal Tactics in the History of Warfare

America officially withdrew its troops from Afghanistan in August 2021, which drew criticism from military officials, politicians and society as a whole, due to the Taliban taking control of Kabul, the country’s capital.