On December 7, 1941, Japan unleashed a devastating surprise assault on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, taking the lives of about 2,400 American service members and propelling the United States into World War II. Among the fallen were three servicemen whose names are seldom mentioned in history, yet their contributions were just as vital as those of their more famous comrades.

These men were stationed on ships engulfed in the chaos of the attack, performing their duties amid deafening explosions, raging fires, and relentless strafing by Japanese planes. While time has dimmed their stories, their bravery and commitment remain woven into the legacy of Pearl Harbor—a turning point that forever altered the course of American and world history.

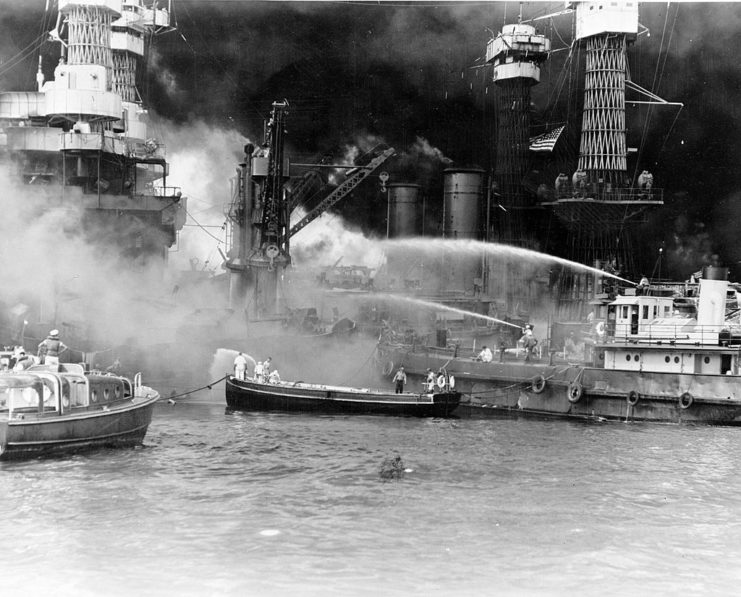

The USS West Virginia was on fire for 30 minutes before sinking

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the USS West Virginia was positioned outboard of the USS Tennessee as part of Battleship Row, along with the USS Arizona, California, Pennsylvania, Nevada, Maryland and Oklahoma. A repair vessel, the USS Vestal, was also moored beside the Arizona.

The USS West Virginia was hit by two overhead bombs and at least six torpedoes during the attack. Immediately after, officers aboard the ship called a “setting condition Zed,” a naval technique wherein all hatch compartments are closed and a portion of the ship flooded to keep it from capsizing.

It was ablaze for 30 hours before sinking and settling along the bottom of the harbor, 40 feet below the water. According to the National Park Service, 106 crew members were killed.

A banging sound was heard inside the ship

The following day, those who’d survived the attack began cleanup efforts, during which they heard a banging noise coming from the USS West Virginia. At first, they thought it was a piece of loose rigging hitting the hull. However, they soon realized they were hearing the sounds of those trapped inside the wreckage.

“When it was quiet you could hear it… bang, bang, then stop. Then bang, bang, pause. At first, I thought it was a loose piece of rigging slapping against the hull. Then I realized men were making that sound – taking turns making noise,” said bugler Dick Fiske.

It was impossible to rescue the men

The muffled sounds of sailors trapped deep within the USS West Virginia haunted the guards who stood watch nearby. Though desperate to help, rescuers faced an impossible dilemma: cutting through the hull risked flooding the compartment, while using a torch could ignite an explosion. Both options were deemed too perilous, leaving the men inside with no way out.

It wasn’t until six months later, when the battleship was finally raised, that salvage teams uncovered the grim truth in storeroom A-111. There, they discovered the remains of three young sailors—18-year-old Ronald Endicott of Washington, 21-year-old Louis “Buddy” Costin of Indiana, and 20-year-old Clifford Olds of North Dakota—huddled together in a final, silent testament to their ordeal.

The Navy never told their families what happened

Flashlight batteries, a manhole for fresh water, and leftover emergency rations were also found. A calendar was discovered with sixteen days crossed off in red pencil, from December 7 to December 23. This revealed that the three men had survived in the wreckage for over two weeks without any way to escape.

News of the discovery spread quickly through Pearl Harbor, but the Navy never informed the men’s families about how long they had remained alive. It wasn’t until decades later, in 1995, that their loved ones finally learned the truth when journalist Eric Gregory wrote a piece about the attack in the Honolulu Advertiser.

All three headstones say they died on the day of the attack

Following its discovery, the calendar was sent to the chief of naval personnel in Washington, D.C., and its current location is unknown. Following their recovery, Endicott and Costin were buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific – known as the “Punchbowl” – in Honolulu. Olds’ remains were returned to his hometown and buried in the local cemetery.

All three of their headstones say they died on December 7, 1941, the day of the attack.

Following it being raised, the USS West Virginia was repaired. When it was returned to service in April 1944, it played a key role in the US forces’ efforts against Japan, and was present at Tokyo Bay during the Japanese surrender. It was decommissioned in 1957 and sold for scrapping two years later.