Long before the silicon chip or the GPS satellite, the United States military looked into the eyes of a common street bird and saw the future of precision warfare. In 1943, as the Navy struggled with the abysmal accuracy of high-altitude bombing, they funded an experiment that sounds like a steampunk fever dream: Project Pigeon.

It wasn’t just a theory. It was a functional, biological guidance system designed to steer the “Pelican” missile directly into the hulls of Axis warships.

The Problem: 1943’s Accuracy Crisis

During the early years of World War II, “precision bombing” was an oxymoron. Even with the top-secret Norden bombsight, most munitions missed their targets by hundreds of yards. Radar was in its infancy, and electronic guidance systems were bulky, fragile, and easily jammed by enemy signals.

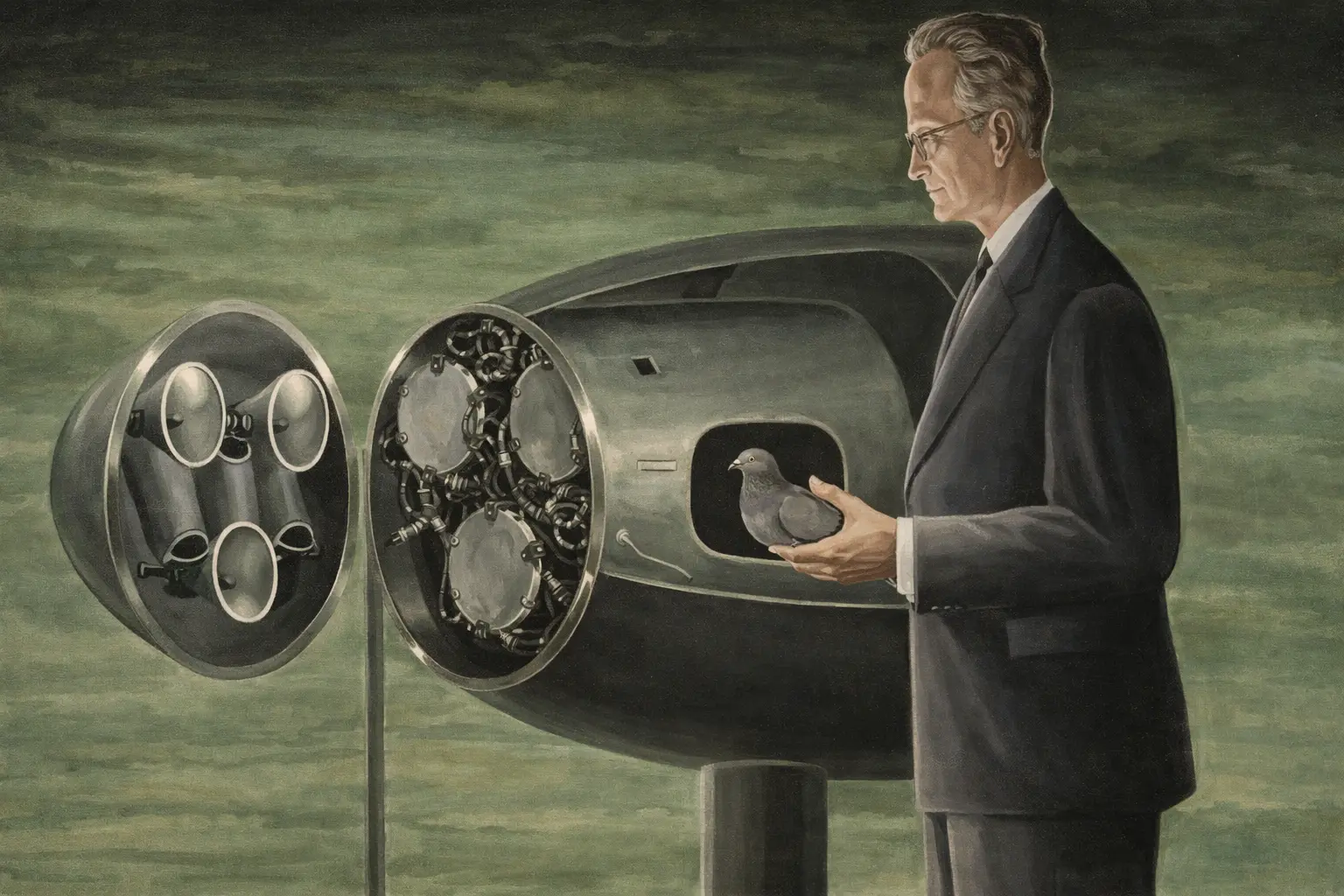

Enter B.F. Skinner, the famed Harvard psychologist. Skinner didn’t see a bird; he saw a highly reliable, organic “computer” capable of rapid data processing. His pitch to the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was simple: If a pigeon can be trained to recognize a shape, it can be trained to steer a bomb.

How the “Organic Control” System Worked

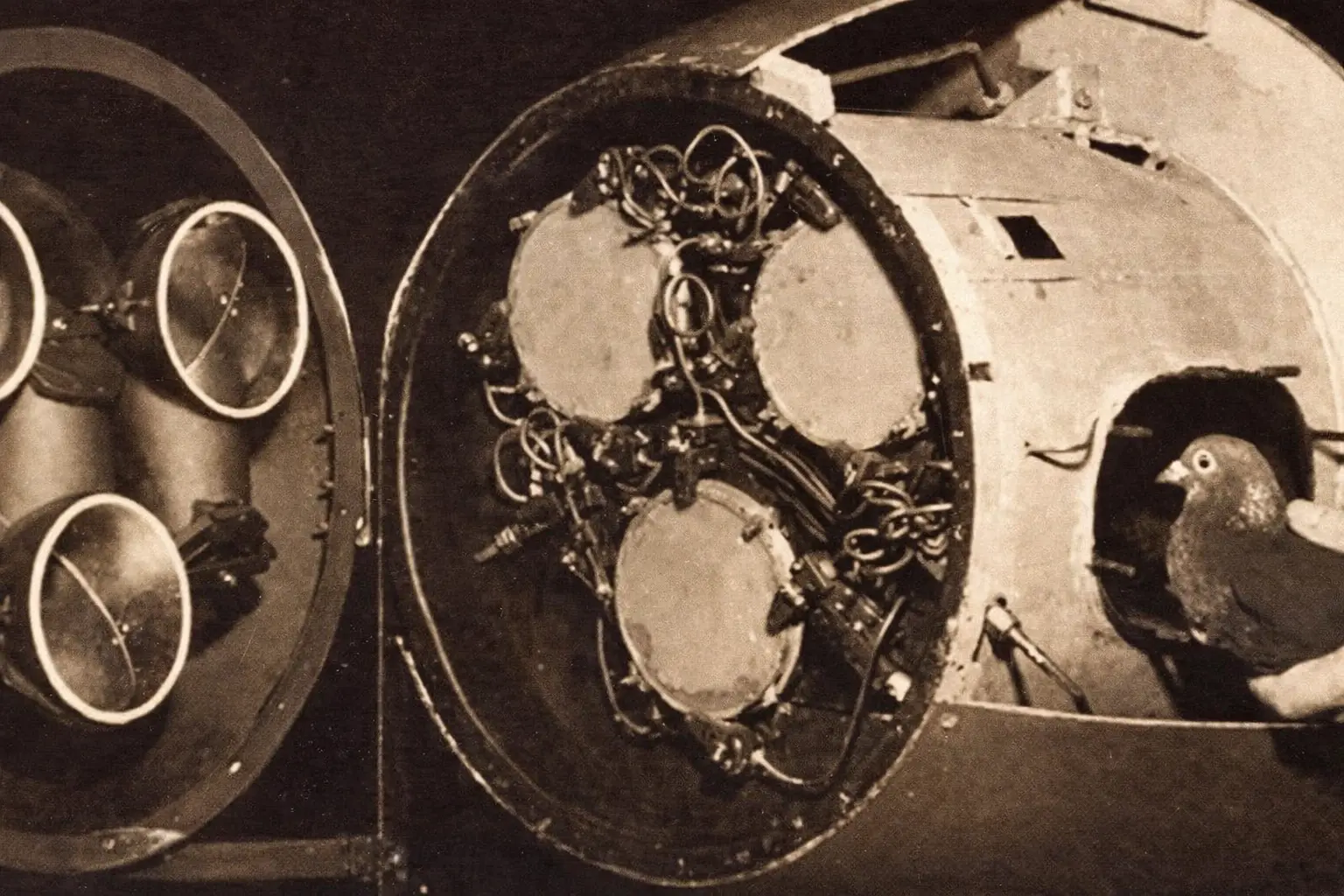

The project, later renamed Project Orcon (short for “Organic Control”), utilized a specialized nose cone for the Pelican glide bomb. The engineering was surprisingly sophisticated for the era:

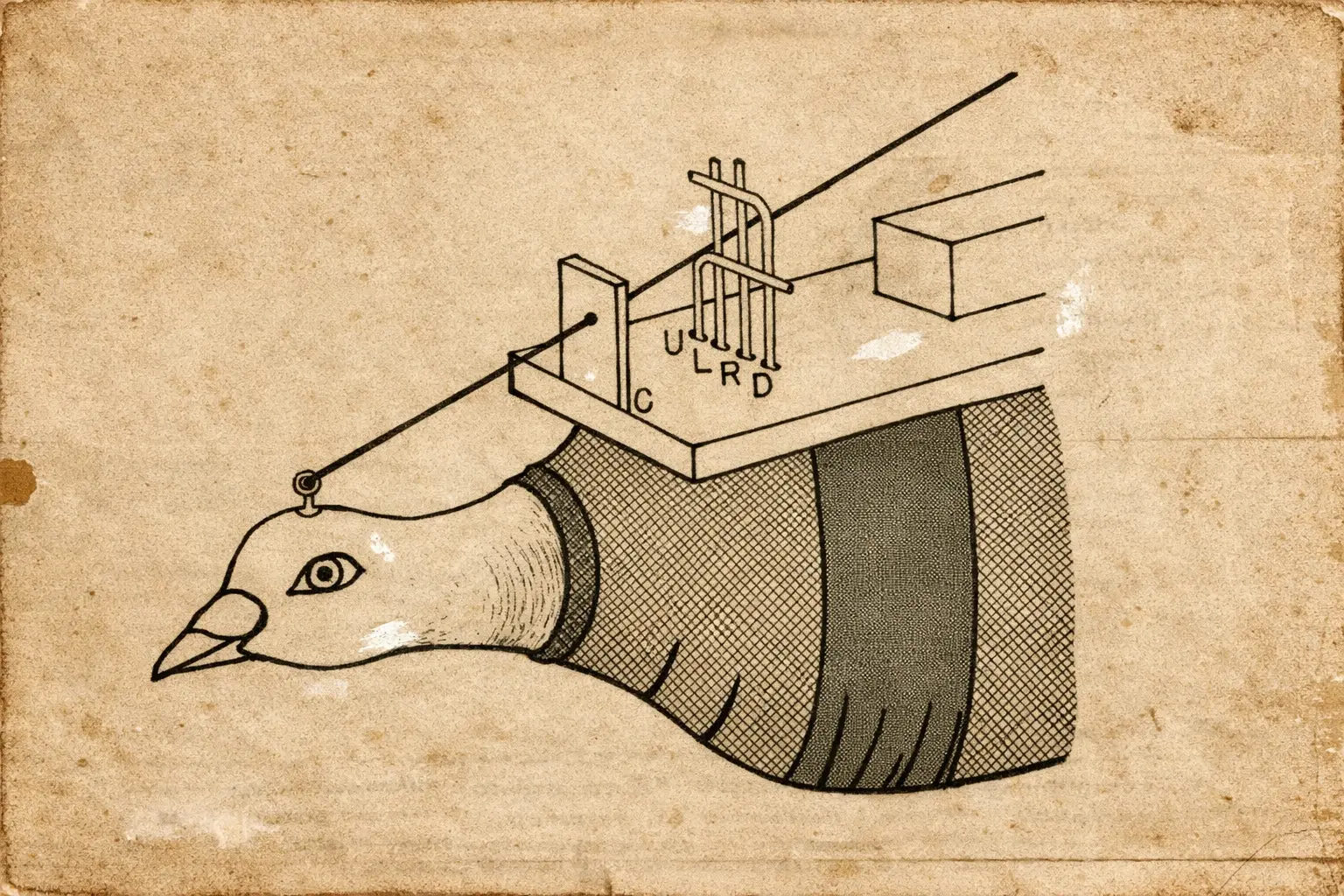

- The Interface: The nose of the missile featured three small windows. A lens projected an image of the surrounding area onto a translucent screen inside.

- The Guidance: One to three pigeons were placed in harnesses behind the screen. Having been conditioned using Skinner’s “operant conditioning” (rewarding behavior with grain), the birds would peck at the image of an enemy ship on the screen.

- The Feedback Loop: If the ship moved off-center, the bird’s pecks followed it. Conductive gold leaf on the screen translated these pecks into electrical signals that moved the missile’s fins, adjusting the flight path in real-time.

Why It Was Grounded

In laboratory trials, the pigeons were nothing short of spectacular. They could track a target at speeds of over 600 miles per hour and demonstrated an uncanny ability to ignore distractions like smoke or light flashes. In many ways, they were more reliable than the vacuum-tube electronics of the time.

High-ranking military officials found the idea of a bird-brained bomb humiliating and absurd. Despite spending $25,000 (a significant sum in 1943) and proving the concept worked, the NDRC pulled the plug on October 8, 1944.

The military ultimately chose to invest in electronic systems that—while less accurate at the time—seemed more “serious” for the dawning atomic age.

The Legacy of Skinner’s Birds

Project Pigeon was officially declassified in 1953. While no pigeon ever flew a combat mission, the project proved that machine-animal interfaces were possible. Today, we see the evolution of this thinking in Machine Learning and Computer Vision—only now, we use neural networks instead of pecking birds to “recognize” a target.

Skinner’s “kamikaze pigeons” remain a fascinating footnote in the history of WWII experimental weapons, reminding us that in the desperation of total war, the line between genius and absurdity is razor-thin.