During the Second World War, Congressman Andrew May committed a major error that severely impacted the U.S. Navy. Following a visit to the Pacific front, he conducted a press briefing to share his insights and boost morale for the war effort. Unfortunately, during his speech, May inadvertently disclosed a critical piece of information—that American submarines were capable of diving to depths far greater than the Japanese had anticipated. While his goal was to highlight the Navy’s power, this revelation handed valuable intelligence to the enemy.

Consequently, the Japanese naval forces altered their depth-charge tactics to neutralize this unexpected edge. Analysts later determined that May’s accidental leak was likely responsible for the sinking of at least ten U.S. submarines and the deaths of about 800 American crew members. This unintended lapse in safeguarding military secrets became one of the war’s most infamous and costly errors.

The May Incident

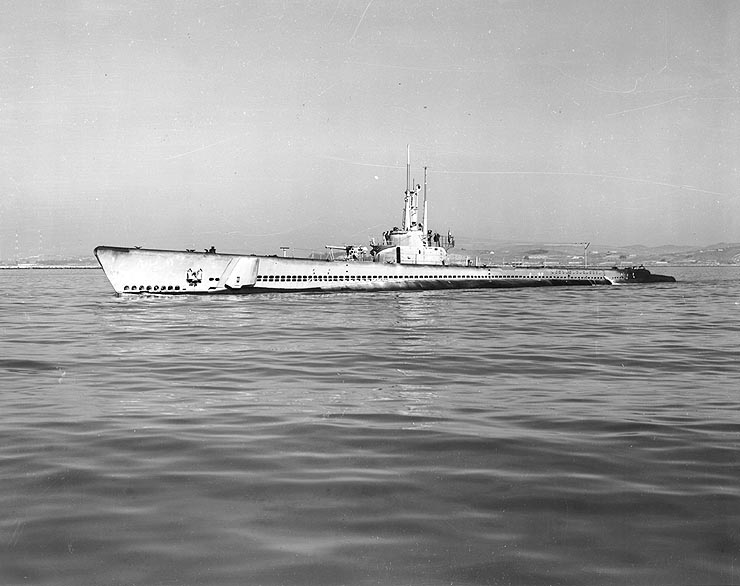

The United States Navy gained significant recognition for its successes after the U.S. entered WWII. Despite the Japanese efforts to destroy American vessels, Allied forces were able to dodge many attacks. This success was largely attributed to the superior capabilities of Balao-class submarines, which could dive as deep as 400 feet—beyond the depth settings of the Japanese depth charges used at the time. This advantage allowed the submarines to evade many of the Japanese counterattacks, contributing to the Navy’s effectiveness in the Pacific theater.

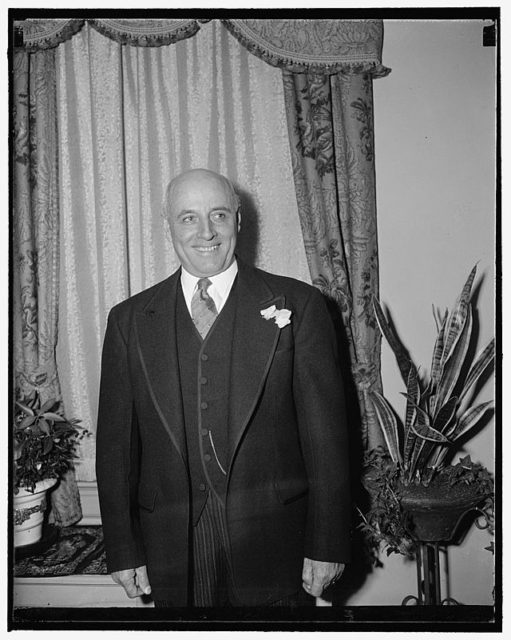

In 1943, Andrew May, chairman of the House Military Affairs Committee, toured American military sites in the Pacific Theater and was granted access to sensitive, classified information. Upon his return in June, he held a press conference where he revealed that American submarines enjoyed a high survival rate because Japanese depth charges were set to explode at insufficient depths.

This revelation quickly made its way through press wires and was published in newspapers across the United States, providing the enemy with valuable intelligence that would later contribute to significant losses for the U.S. Navy.

The fallout of a blabbermouth

“I hear Congressman May said the Jap depth charges are not set deep enough,” he said. “He would be pleased to know that the Japs set them deeper now.”

After the press conference, the Navy’s Pacific Submarine Fleet issued a report stating that Japanese anti-submarine forces still hadn’t figured out the maximum depth U.S. submarines could reach. However, the report did not confirm whether May’s statements directly influenced Japanese tactics.

Alleged war profiteering

Andrew May’s time in office was riddled with scandal, and his notorious press conference was just the beginning. At the onset of World War II, he formed a relationship with two entrepreneurs from New York, Henry and Murray Garsson. Despite lacking any prior experience in arms manufacturing, the Garsson brothers viewed the war as a lucrative opportunity to secure government deals for producing munitions.

While chairing the House Military Affairs Committee, Andrew May exploited his influential role to sway Army ordnance officials and other government figures in favor of the Garsson brothers. With his backing, the brothers landed lucrative defense contracts, enjoyed preferential treatment, and even arranged draft deferments for select individuals. In return, May accepted substantial bribes—an arrangement that remained concealed until a postwar Senate inquiry brought it to light.

The probe swiftly escalated into a major scandal, uncovering widespread war profiteering and alarming deficiencies in the munitions the Garssons supplied. Among the most troubling findings was that their 4.2-inch mortar rounds were equipped with defective fuzes, leading to premature explosions. These failures were directly linked to the deaths of 38 U.S. servicemen.

Paying for his actions… Maybe?

Andrew May’s mistakes during the war caught up with him—he lost his re-election bid in 1946. Not long after, he was put on trial for federal bribery charges. On July 3, 1947, after less than two hours of jury deliberation, he was found guilty. Although he tried to avoid serving time, he ended up spending nine months in a federal prison.

Murray and Henry Garsson were also sentenced to prison.

Even with his damaged reputation, May still had some pull in Democratic political circles. Thanks to those connections, he was able to get a full pardon from President Harry Truman in 1952. However, he wasn’t able to make a political comeback and instead returned to Kentucky, where he practiced law until he died.