Charles Robert Jenkins was an American soldier who defected to North Korea in 1965. Contrary to what it may seem, his plan was never to remain there, as he simply feared having to serve in Vietnam. Despite this, he wound up spending over 39 years of his life under the regime’s watchful eye, before returning to the United States in 2004, where he faced a court-martial.

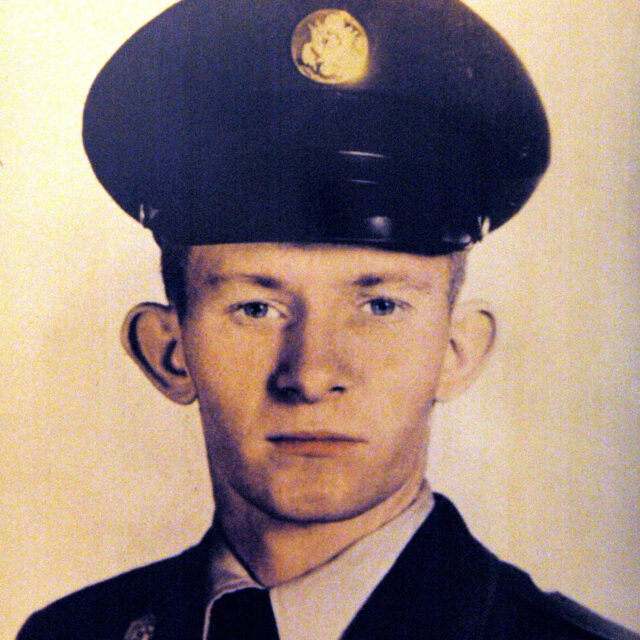

Charles Robert Jenkins enlisted when he was 15 years old

Charles Robert Jenkins was born in Rich Square, North Carolina, on February 18, 1940. During his upbringing, he suffered a sports injury and the loss of his father, both of which contributed to him never graduating from Rich Square High School.

Without a high school diploma, Jenkins’ job prospects were limited. This led him to enlist in the North Carolina National Guard, with whom he served from 1955-58 – the majority of his teenage years. Following his honorable discharge, the then-18-year-old joined the US Army and was assigned to Fort Hood (today Fort Cavazos), Texas, as a light weapons infantryman.

It wasn’t long before Jenkins volunteered to serve with the 7th Infantry Division in South Korea. He was deployed in August 1960 and returned to the United States in September of the next year. He was subsequently assigned to the 3rd Armored Division and deployed to West Germany, where he remained until 1964.

Deserting the US Army

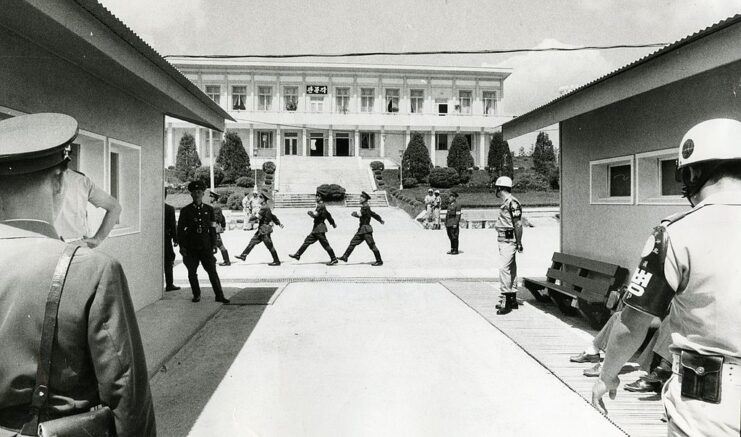

In 1964, Charles Robert Jenkins volunteered for a second deployment to South Korea, serving in the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). This time around, he was assigned to the 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division.

On January 5, 1965, Jenkins made the decision that forever changed his life. Rumors had been swirling that his regiment was going to be deployed to Vietnam. This, compounded by increasingly aggressive patrols, led the sergeant to cross the DMZ into North Korea. He’d planned to claim asylum through the Soviets, who would then trade him back to the United States during a prisoner exchange.

That fateful night, Jenkins put away 10 beers before going on patrol with his comrades. Around 2:30 AM, he told them he’d heard a noise and went to check it. This was when he made his great escape. As he approached the DMZ, he took the ammunition out of his M14 rifle and tied a white shirt to the top as a sign of peace.

Jenkins then crossed over into North Korea, expecting to see the US again very soon. Instead, he was captured, interrogated and held prisoner for 39 and a half years.

Immediately regretting his decision

It wasn’t long after his capture and detention that Charles Robert Jenkins regretted his decision to defect to North Korea; it was not the experience he’d expected it to be.

In a 2006 interview with British publication The Independent, he called his desertion “the biggest mistake I ever made,” and in his 2008 memoir, The Reluctant Communist: My Desertion, Court-Martial and 40-Year Imprisonment in North Korea, wrote that hadn’t realized the nation was essentially a giant “prison.”

He also explained his mindset at the time, writing, “I was not thinking clearly. But at the time my decisions had a logic to them that made my actions seem almost inevitable.”

Charles Robert Jenkins was housed with other defectors

Just under two weeks after crossing the DMZ, Charles Robert Jenkins’ defection was announced on North Korean radio, which stated his decision was “because of disgust with conditions in South Korea and that he believed life was better under the Communists.” The United States confirmed him to be a deserter based on four letters he’d sent to his mother, one of which read, “Forgive me, for I know what I must do. Tell my family I love them. Love, Charles.”

Jenkins was housed with three other American deserters while under the regime’s watchful eye:

- James Dresnok, who defected in August 1962.

- Larry Abshier, who crossed the DMZ in May 1962.

- Jerry Parrish, who deserted his post in 1963.

The conditions the four were held in were horrible; they shared one room and were beaten when they failed to properly memorize the works of Kim Il-Sung. While the group had decided to cross over into North Korea, they hadn’t necessarily planned to remain. In 1966, they attempted to follow Jenkins’ original plan to seek asylum through the Soviet embassy, but they were unsuccessful.

Working for the North Koreans

Years later, the four were declared citizens and given their own homes, jobs and, eventually, wives. This didn’t, however, change their living conditions. Charles Robert Jenkins later wrote he “suffered from enough cold, hunger, beatings and mental torture to frequently make me wish I was dead.”

Even when they were made “citizens,” the group wasn’t trusted by their captors. Their houses were bugged and surrounded by barbed wire to prevent escape. The men were also used in a series of propaganda films, playing evil Americans, and Jenkins taught English classes to North Korean spies and servicemen. His strong Southern accent, however, eventually led to him being dismissed from this role.

Charles Robert Jenkins marries Hitomi Soga

In 1980, Charles Robert Jenkins was introduced to Hitomi Soga, a Japanese nurse who’d been kidnapped a few years prior to serve as a teacher for North Korean spies. Theirs was a forced union, with the ceremony occurring only a few weeks after they were introduced.

Despite having little choice in the arrangement, the two came to care for each other deeply, with Jenkins telling The Independent, “When I met her, my life changed a lot. Me and her together – I knew we could make it in North Korea. And we did.”

In the coming five years, they had two daughters, Mika (1983) and Brinda (1985).

Hitomi Soga attempts to free her husband

It was thanks to Hitomi Soga that Charles Robert Jenkins was finally able to leave North Korea. When the Japan-North Korea Pyongyang Declaration was signed in 2002, she and four other captives were allowed to visit Japan for 10 days – she never returned. Instead, she worked with the Japanese government to help convince the United States to pardon her husband. Her attempts, however, were unsuccessful.

Had he followed Soga to Japan, Jenkins risked capital punishment for his desertion, as the statute of limitations was 40 years – he’d been gone for 39 and a half. Therefore, he made the difficult decision to remain in North Korea with his daughters.

Charles Robert Jenkins is finally freed

Eventually, North Korea allowed Charles Robert Jenkins to leave, and he reunited with his wife in Indonesia. That made him the only post-Korean War American defector to ever leave the restrictive country. The evidence of his mistreatment was obvious. He was 100 pounds, had lost his appendix and a testicle, and part of his US Army tattoo had been cut off without proper anesthesia.

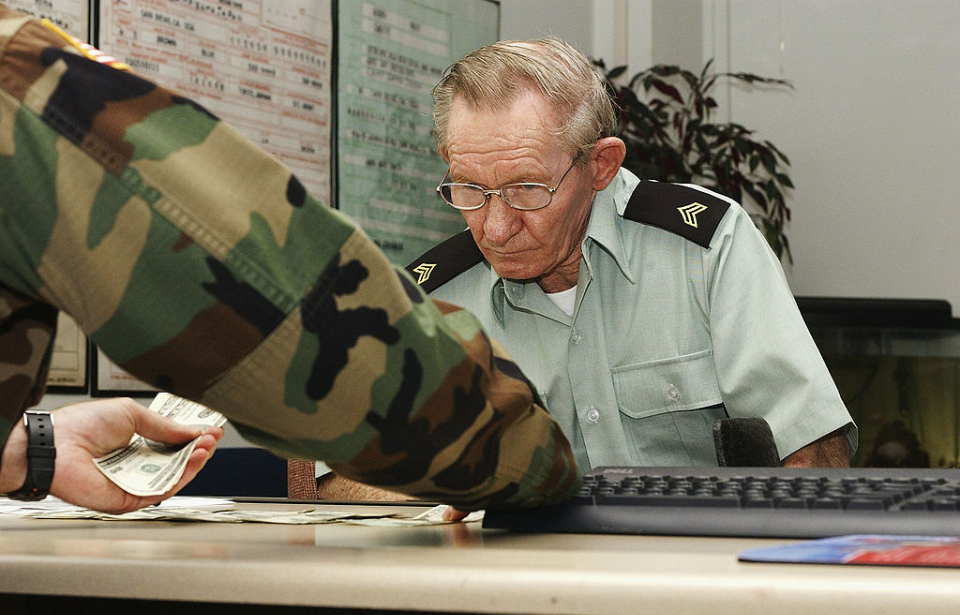

Although Japan had promised Hitoma Soga, Jenkins and their daughters residency, there was still the matter of his court-martial. Jenkins arrived at Camp Zama, Japan, on September 11, 2004, where Lt. Col. Paul Nigara was awaiting him. Jenkins, by then 64, greeted him with a salute, saying, “Sir, I’m Sergeant Jenkins and I’m reporting.”

Jenkins’ trial wasn’t held until November 3, 2004. He pleaded guilty to desertion and aiding the enemy by teaching English. He was initially sentenced to six months confinement, but this was later changed to 30 days. The former Army soldier also forfeited all his back pay, was demoted to the rank of private and received a dishonorable discharge.

Adapting to civilian life

Despite the ruling, Charles Robert Jenkins was released on good behavior after 25 days. He was reportedly given pay for the time served. In an interview years later, he said that the sentence was “all a big set-up for the outside world so it looked like justice was done.”

Once his time was served, Jenkins and his family moved to his wife’s childhood home, with a trip made to North Carolina to see his aging mother. Although he’d escaped North Korea, he lived the rest of his life worried they’d come for him. He recounted his experiences in his aforementioned memoir.

More from us: National Emergency Command Post Afloat: The ‘Floating White Houses’ for Times of Nuclear War

Jenkins lived out the rest of his life as a major celebrity in Japan, receiving permanent residency in July 2008. In his spare time, he followed his passion for motorcycling and worked at a local museum. On December 11, 2017, at the age of 77, Jenkins passed away. The cause was attributed to cardiovascular disease.