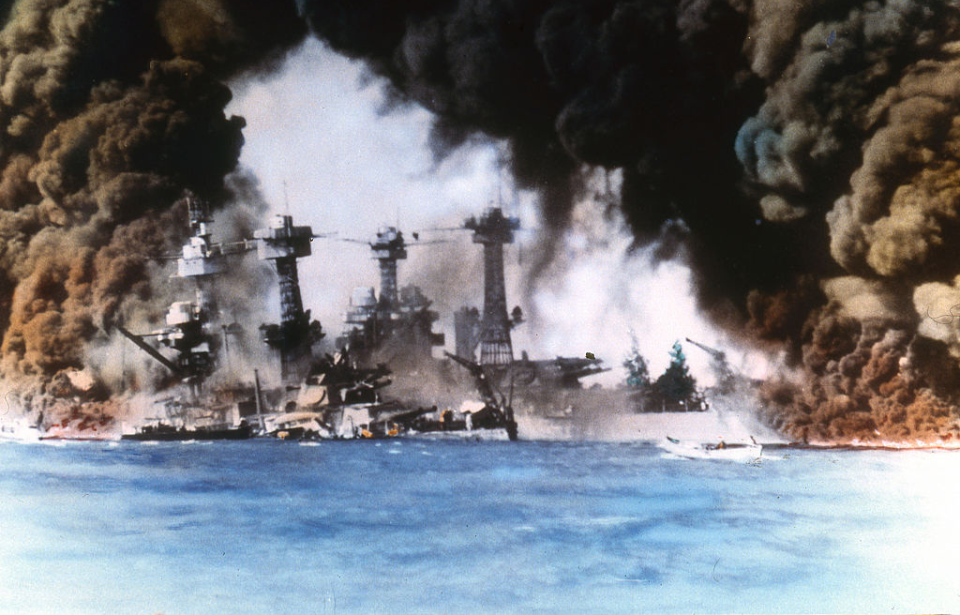

Pearl Harbor remains a pivotal episode in American history, but its legacy is frequently obscured by lingering myths, partial truths, and exaggerated accounts. In the chaotic aftermath of the December 7, 1941, attack, panic and rumors spread rapidly, giving rise to narratives that have endured for decades.

A more accurate understanding requires distinguishing legend from reality. Examining the historical record helps dismantle these misconceptions and clarify what actually occurred. Below are four common myths about Pearl Harbor, along with the evidence that sets the record straight.

Pearl Harbor was the only target

One common myth is that Pearl Harbor was the only place attacked by Japan on December 7, 1941. While it’s the most well-known, it was actually just one of six coordinated assaults. That same day, Japan also struck Guam, Wake Island, Midway, Thailand, and Malaya. Because of time zone differences, some of these attacks are listed as happening on December 8.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a single part of a larger Japanese campaign to take control of the Pacific. In the months that followed, this strategy mostly worked—Japan gained ground across the region, with only Midway and Pearl Harbor managing to hold out during Second World War.

The reason this myth still exists is because the Pearl Harbor attack was the most damaging. It caused the highest number of American casualties and made the war feel very real to people in the United States.

Japanese-Americans were the only ones detained after the attack

A common belief is that only Japanese-Americans were interned after the attack on Pearl Harbor, but this is not entirely accurate. This myth likely emerged because Japanese-Americans endured the harshest treatment, including mass internment, which has rightfully received significant attention in historical accounts and public memory.

In reality, following the attack, more than 3,000 individuals were arrested by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the U.S. Army’s G-2 intelligence unit, and the Office of Naval Intelligence due to suspected subversive activities. These arrests weren’t limited to Japanese-Americans—they also included people of German and Italian descent.

Throughout World War II, around 120,000 Japanese-American citizens were sent to internment camps. However, around 11,000 German-Americans were also interned, and an estimated 600,000 people of Italian descent faced various restrictions, such as travel bans and curfews.

While Japanese-American internment was on a larger scale and more severe, it is important to acknowledge that citizens of several ethnic backgrounds were impacted by wartime paranoia and suspicion.

A quick and decisive response by the United States

The idea that the US government and military responded to the devastating attack quickly and decisively is a popular one, but it’s a myth. In the months following what took place, the country suffered multiple defeats in the Pacific region.

This myth may have started when a rumor spread throughout the country on December 8, 1941, that the US Navy was in pursuit of the Japanese fleet. This is false, with Gen. Douglas MacArthur actually pleading for more naval assistance. In reality, a telegram was sent to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, asking for assistance and submarines to target Japanese vessels. This went unanswered and is believed to have led to the fall of the Philippines.

The first major offensive by the US occurred in February 1942, when the Pacific Fleet launched attacks on the Marshall and Gilbert Islands. Before these raids, the last successful engagement had occurred prior to Pearl Harbor.

Pearl Harbor convinced the United States to join World War II

More from us: Tuskegee Airmen: The African-American Pilots Who Broke Barriers in World War II