Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II marked the conclusion of one of history’s most devastating conflicts and the beginning of a new global order. While Germany had already fallen in May 1945, Japan continued to fight fiercely across the Pacific. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are often portrayed as the main reasons behind Japan’s capitulation, but the reality was more nuanced. The Soviet Union’s surprise declaration of war and rapid invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria delivered a critical shock—convincing Japan’s leaders that the situation was hopeless and pushing them toward unconditional surrender.

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Two key events that led to Japan’s surrender were the atomic bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On the morning of August 6, 1945, the former was subjected to an attack that decimated the city and inflicted a devastating human toll, with between 90,000-146,000 killed both during Little Boy‘s detonation and after, due to the effects of radiation exposure and burns to the skin.

Just three days later, on August 9, Nagasaki experienced a similar fate, with the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Bockscar dropping the atomic bomb Fat Man on the city, located some 261 miles from Hiroshima. Just like the latter, Nagasaki suffered extensive losses, with between 60,000-80,000 citizens perishing within four months of the attack.

Between both detonations, it’s estimated around 129,000-226,000 people lost their lives – a truly devastating number.

The atomic bombs not only demonstrated the US military’s superiority, but also signaled the emergence of a new and terrifying era in warfare. The realization that further nuclear attacks could obliterate Japanese cities forced leadership to reconsider their position; the fear of additional devastation, coupled with the understanding that conventional defenses were futile against such power, significantly influenced Japan’s decision to surrender.

Declaration of war by the Soviet Union

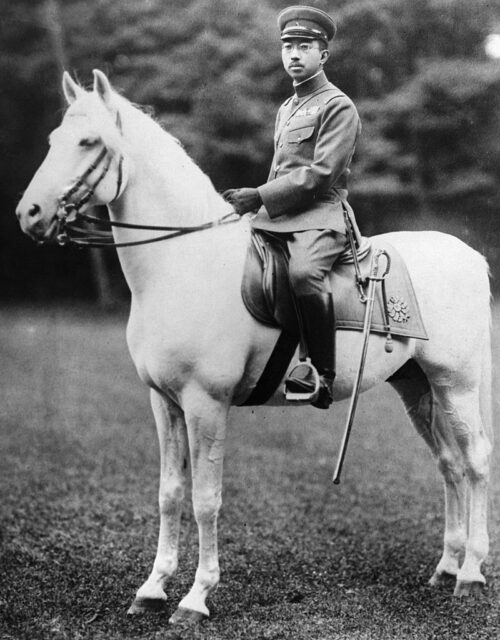

The impact of the atomic bombings was intensified by the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan on August 8, 1945, delivering a decisive blow to the already dim prospects of the Japanese military. Japanese leaders had underestimated the threat posed by the Red Army, assuming they would not face Soviet forces until the spring of 1946. Emperor Hirohito had even sought assistance from Joseph Stalin, hoping he could help mediate between Japan and the United States.

The sudden Soviet invasion of Manchuria caught Japan off guard, leading to 650 of the 850 occupying troops being killed or wounded within the first two days of fighting. This unforeseen attack killed any lingering hopes for a negotiated peace and showed Japan’s growing geopolitical isolation.

Faced with the grim reality of a two-front war, Japan’s political and military leaders realized their position was unlikely to hold, prompting even Emperor Hirohito to encourage them to reconsider surrender.

Japan’s military resources were beginning to dwindle

By 1945, Japan’s ability to wage war had been effectively exhausted. Years of grueling conflict had drained its military power, while the Allies’ relentless island-hopping campaign stripped away key strongholds one by one. A crippling naval blockade choked off imports, and sustained bombing raids reduced entire cities to rubble, leaving the nation’s infrastructure in ruins.

For civilians, daily life had become a fight for survival. Food and fuel were desperately scarce, forcing many to subsist on meager rations averaging just 1,680 calories a day—barely enough to live on. With most able-bodied men drafted into the military, Japan’s home front was left vulnerable and weary.

Confronted by overwhelming military losses, economic collapse, and a starving population, Japan’s leaders recognized that further resistance was impossible. Reluctantly, they began to seek a way to end the war on whatever terms they could secure.

Japan wanted to preserve its Emperor system

One of the central concerns for Japanese leaders during surrender talks was the future of the emperor. They feared that a fully unconditional surrender could force the dissolution of the imperial system—a move they believed would shatter the nation’s identity and morale. Determined to safeguard the throne, they sought assurances that the monarchy would endure in some form.

This concern eventually culminated in the 1946 “Humanity Declaration,” where Emperor Hirohito publicly renounced his divine status. No longer regarded as a living god, he instead became a purely symbolic figure—“the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people.” This redefinition of the emperor’s role was officially cemented in Japan’s new postwar constitution, transforming the monarchy into a ceremonial institution with no political power.

Facilitating Japan’s surrender

The process of facilitating Japan’s surrender was marked by significant diplomatic and communicative efforts. Behind the scenes, diplomats and intermediaries worked tirelessly to establish a channel of communication between Japan and the Allied forces. These efforts were aimed at finding a mutually acceptable solution that would allow the country to surrender while addressing the concerns of all parties involved.

With all the aforementioned factors piling on top of the each other, the decision was ultimately made for Japan to surrender, with Emperor Hirohito announcing the news to the public via a radio broadcast on August 15, 1945.

The first time he’d spoken to average citizens directly, the emperor explained, “The war has lasted for nearly four years. Despite the best that has been done by everyone – the gallant fighting of the military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of our servants of the state, and the devoted service of our one hundred million people – the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage, while the general trends of the world have turned against her interest.”

More from us: Paul Tibbets Dropped the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Was Given No Funeral or Gravestone

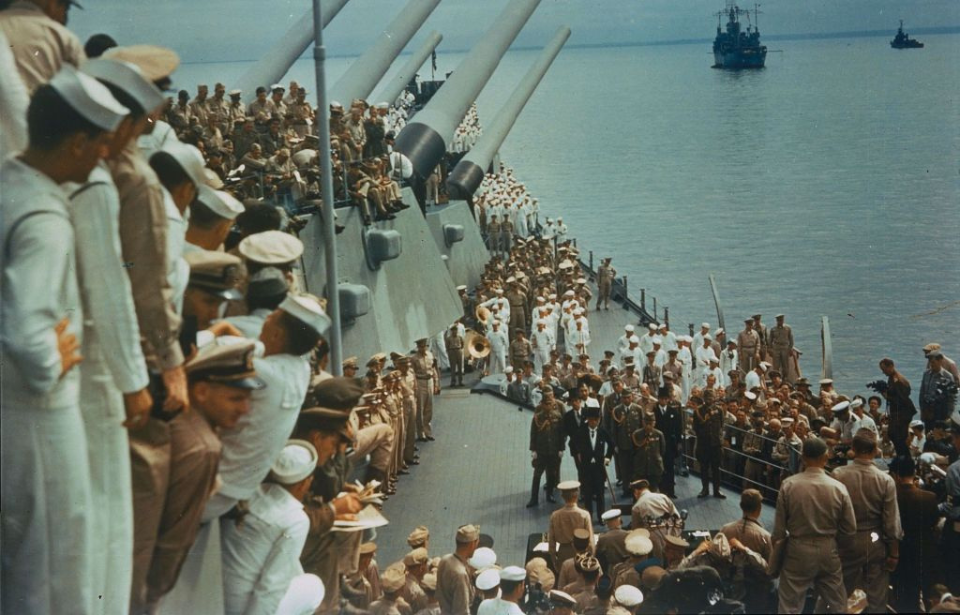

Just over two weeks later, aboard the American battleship USS Missouri (BB-63), the Japanese Instrument of Surrender was signed. Those present included representatives from the Empire of Japan and the Allied nations, with the most notable being Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Fleet Adm. Chester Nimitz and Chief of the Japanese Army General Staff Gen. Yoshijirō Umezu.