On 9 February 1945, the last German forces on the west bank of the River Rhine were defeated by the French and Americans. The defeat of these troops, who had held onto an area referred to as the Colmar Pocket, was a significant strategic moment, securing a defensive line along the Rhine.

It was also a symbolically important moment. Alsace, the region in which the Pocket existed, had been a source of conflict between France and Germany for nearly a century. It had been taken from France by the Germans in the Franco-Prussian war (1870-71), retaken by the French at the end of the First World War, seized once more by the Germans in 1940, and now it became French again.

Borders had been pushed back to where the French felt they should be, and from now on troops in the region would advance into Germany.

Background

In November 1944, the Allies broke German defences in the Vosges Mountains. Alsace and Lorraine – the region of France most fiercely defended by the Axis forces – were largely in Allied hands. German forces were driven back to the Rhine on the northern and southern edges of the Allied advance.

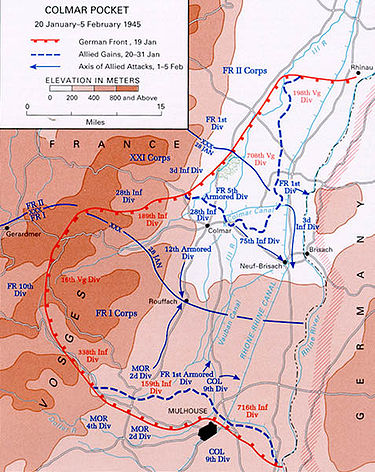

But in the centre, the Germans held onto a bridgehead on the west bank of the river. Centred on the town of Colmar, this area was 40 miles wide and 30 miles deep. It became known as the Colmar Pocket.

Weary from six months of fighting, their logistics stretched thin, the Allied forces lacked the fresh troops and supplies they needed to push hard. Small villages of sturdy stone construction gave the Germans strong defensive positions. A harsh winter, with a metre of snow and temperatures as low as -4⁰ C, stalled the advance.

Southern Attack

Having had time to recover and prepare, the Allies began a concerted attack on the Colmar Pocket on 20 January 1945. Targeting the southern edge of the pocket, the attacking forces of the French I Corps consisted largely of colonial troops – experienced veterans far from their familiar climate of Morocco.

Turning the terrible weather to their advantage, the French achieved surprise by attacking during a snowstorm. But after the initial assault, the weather and terrain counted against them, making advances difficult. The Germans had prepared their positions, laying minefields and finding good firing spots. Though a German counterattack on 24 January was unsuccessful, by then the French advance had largely stalled, having taken heavy casualties for a few miles of ground.

Northern Attack

With German forces drawn off to the south, the French and Americans launched another attack on the northern flank of the pocket on 22 January. The aim was to bypass Colmar itself and cut off railway lines supplying the Germans.

Again, the fighting proved difficult. The bridge at Maison Rouge collapsed under the weight of a tank, preventing armour from advancing with the infantry there. Icy conditions made it impossible for troops to dig foxholes, leaving them exposed in the face of German counterattacks.

Those counterattacks came thick and fast, but the Allied forces were able to stop each one, keeping up a steady advance. There were several acts of great heroism. PFC Jose F. Valdez was fatally injured after engaging in a firefight with enemy infantry and a German tank, allowing his patrol to retreat to friendly lines, an action that earned him a posthumous Medal of Honor. Lieutenant Audie Murphy earned the Medal of Honor for halting a German advance by climbing a burning tank, using its heavy machine gun to blast the enemy, and calling in an airstrike on his own position.

Resistance in the north began to weaken, and on 1 February French forces in the north reached the Rhine.

Collapse

Following reports of heavy casualties, the Allies sent reinforcements to bolster their attacks. General Milburn’s XXI Corps, which now incorporated French as well as American troops, was given the task of taking Colmar itself.

Meanwhile, the Germans were in chaos. They had not been able to work out the Allied objectives, believing this was just an opportunistic advance. Withdrawing units became mixed up and confused. Hitler would not order a retreat across the natural defensive barrier of the Rhine.

An advance now began near the centre of the pocket. One by one, key towns were taken. Biesheim fell on 3 February after an entire day of fighting. Fortified Neuf-Brisach, a key position, was taken on 6 February after French children showed the Americans an undefended route in.

The town of Colmar was attacked by the Allies on 2 February, and the Germans driven out the following day. The French 152nd Infantry Regiment, which had been garrisoned in Colmar before the war, finally returned to a home which had been in enemy hands for nearly five years.

On 5 February, the separate advances met up at Rouffach, splitting the Pocket in two. Four more days of fighting followed as the Allies covered German routes of retreat and assaulted positions still held by Axis forces. Artillery and aircraft bombarded significant clusters of German troops, driving them back.

On 9 February, the German rearguard was destroyed at Chalampé, and the Germans demolished the bridge over the Rhine there. With no significant German forces left in Alsace, the Colmar Pocket had fallen.

Outcome and Importance

The fighting in the Colmar Pocket wiped out most of the experienced troops in the German 19th Army, and when it reformed it was made up in large part of inexperienced recruits. The Pocket’s fall freed up Allied troops to join Operation Undertone, the advance into Germany through the Siegfried Line, without worrying about German troops advancing into a bridgehead west of the Rhine.

And Alsace was back in French hands – a moment of huge symbolic importance and national pride.