In June 1942, the Nazi German occupiers of Czechoslovakia destroyed the mining village of Lidice. It was wiped off the map so completely that even its memory might have been forgotten. But neither the people of Czechoslovakia nor the rest of the world would let the Nazis win.

Czechoslovakia Under the Nazis

Czechoslovakia was the victim of general unwillingness to confront Nazi Germany. In 1938, France and Britain allowed Germany to occupy part of Czechoslovakia under the Munich Agreement. In March 1939, Slovakia declared independence and aligned itself with Germany. The remainder of the country was swallowed up by Germany, Poland and Hungary.

German-occupied Czechoslovakia was turned into the Reich Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. But it proved a difficult territory to keep in line. The Germans became increasingly worried about resistance there, which was supported by the government in exile.

By 1941, Hitler believed that the man in charge of the Protectorate, Reich Protector Konstantin von Neurath, was being too lenient. Von Neurath was sent away, supposedly for health reasons, and Gestapo head Reinhard Heydrich took his place. Heydrich, who was responsible for much of the planning for the Holocaust, was ruthless in his suppression of dissent. His activities in Czechoslovakia earned him nicknames such as “The Butcher of Prague” and “Hangman Heydrich”. Hitler himself referred to him as “the man with the iron heart”.

Murder in Heydrich’s Name

On May 28th, 1942, a pair of operatives for the Czech government in exile, trained by the British and aided by the Czech resistance, tried to assassinate Heydrich. He was severely wounded and died in hospital from an infection on June 4th.

Enraged at the attack on one of their leaders, the Nazis set out to make the consequences so unbearable that no-one would ever try it again. They hunted down every last connection to the resistance that they could. The assassins, along with five other men linked to the resistance, were killed in an attack on their hideout in an orthodox church. Others were rounded up, imprisoned and killed.

The attacks stretched beyond known rebels. At least 5,000 Czechs were killed in revenge for Heydrich’s death, including 3,000 from the Jewish ghetto.

Why Lidice?

On June 3rd, a letter arrived at a factory in Slaný. Written by a man named Vaclav Říha, it was addressed to one of the factory workers, Anna Maruščáková, with whom he had been having an affair. The vaguely worded letter implied that Říha was joining the resistance – not true, but his excuse for ending their relationship.

Maruščáková was off sick. The factory owner opened the letter, found it suspicious, and reported it to the Germans. Maruščáková was arrested, as was Říha, and the truth came out. They were both executed later in the year.

In the process of her interrogation, Maruščáková revealed that two men from the mining village of Lidice were in Britain, fighting for the allies. Knowing that the British had parachuted agents into the Protectorate the previous December, the Gestapo concluded that these men were among the paratroopers and Heydrich’s assassins.

The Nazis were wrong. Neither of the assassins was from Lidice. But the village’s fate had been sealed.

Destroying a Community

Hitler was furious at the death of his friend Heydrich, and at the defiance shown by the Czechs. He determined not just to destroy Lidice, but to destroy the memory of it. To make it as if the village had never existed.

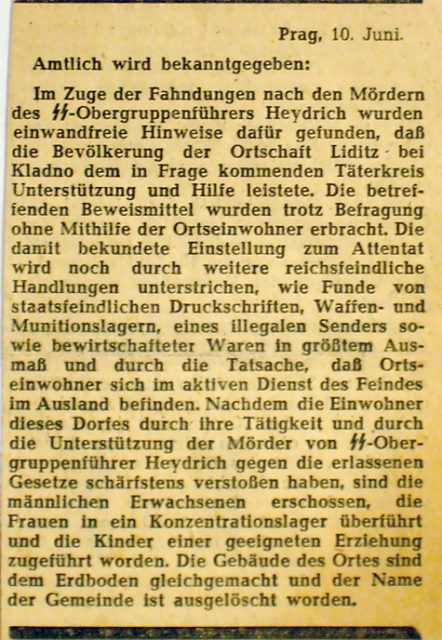

On the night June 9th, men of the Ordnungspolizei (Order Police) and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the SS intelligence agency, surrounded Lidice. At seven the next morning they moved in, and their grim work began.

All men aged 15 and over were lined up and shot. The bodies piled up until the firing squad had to step back to make space for new groups of victims. Nine men and two boys who were away from the village were later shot in Prague.

Every building in the village was burned down, and their remains demolished with explosives.

Four pregnant women had their foetuses forcibly aborted and were then sent to extermination camps.

The remaining women were taken to Ravensbrück camp. There they laboured for the Germans, many dying as the guards worked to isolate them.

The children were sent to Łódź in Poland. They received minimal care, and many died. A few were chosen for Germanisation, leading to adoption by SS families. They were not told of their origins.

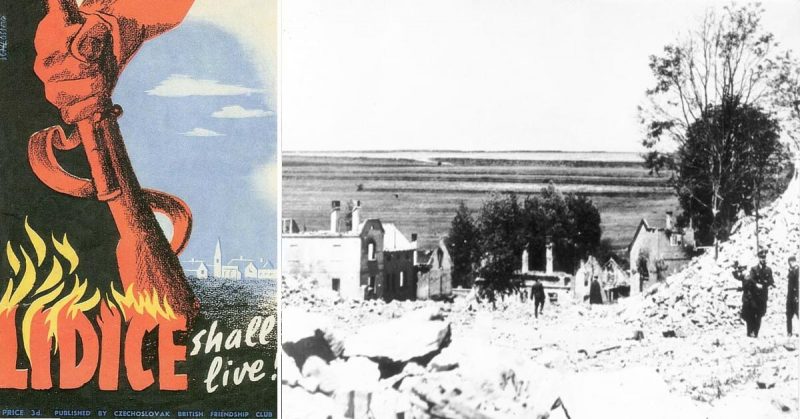

The remains of Lidice were bulldozed, the landscape reshaped, even the course of the stream changed. Nothing remained of a once thriving community.

The World Remembers

But for Hitler’s destruction of the village to cause fear, he had to tell the world about it. And so, instead of being forgotten, Lidice became a rallying cry against the Nazis.

At Ravensbrück, other inmates struggled to prevent the Lidice women from being isolated.

Towns in Brazil, Mexico, Panama, the United States and Venezuela changed their names to incorporate that of Lidice in remembrance. At San Jerónimo Lidice in Mexico, the massacre is still commemorated every year. Monuments, books, plays, films, street names, all of these were used to keep Lidice’s memory alive.

The Staffordshire Miners

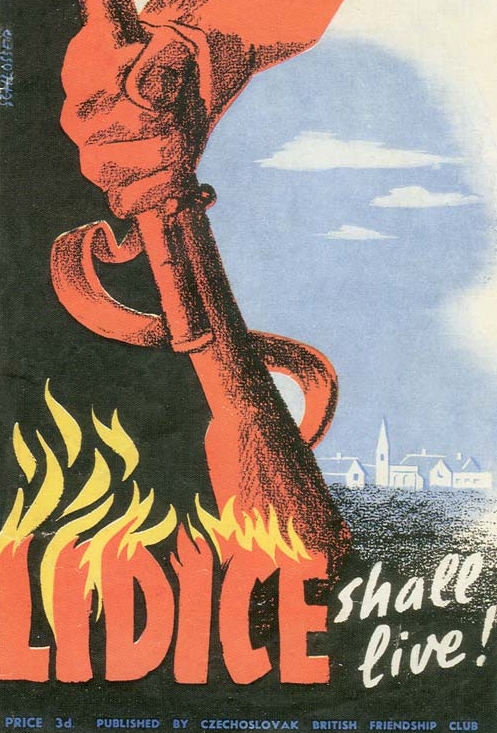

In the British city of Stoke-on-Trent, Dr Barnett Stross heard about Hitler’s declaration that “Lidice shall die forever” and responded with the opposite – “No. Lidice shall live.”

Stoke had a strong mining community, which Stross mobilised. Together with Arthur Baddeley, president of the North Staffordshire Miners’ Federation, he launched the Lidice Shall Live campaign on September 6th, 1942. Czech President Dr Edvard Beneš attended the launch event. Miners across Stoke-on-Trent and North Staffordshire pledged a day’s wage each week to a fund to rebuild Lidice. It was a big sacrifice in an economy already strained by the war, but the miners recognised that it was nothing compared with the suffering of Lidice. By the end of the war, they raised £32,000 – equivalent to over £1,000,000 today.

Following the war, Lidice was rebuilt – not on the same site but nearby, so that the site of the atrocity could remain and be remembered.

Lidice shall live.