Nearly five hundred years after the Teutonic Knights were routed at Grunwald, the sting of that defeat still lingered in the German historical consciousness. So when German armies overwhelmed Russia’s Second Army in August 1914, early in World War I, commanders recognized a chance to score not only a strategic victory but also a symbolic one.

In a swift, four-day campaign, German forces surrounded and destroyed the Russian formations. To underscore the deeper historical message, German officials christened the engagement the Battle of Tannenberg—an intentional reference to the disaster of 1410. By doing so, they framed the triumph as long-delayed vengeance, a symbolic restoration of national honor centuries after the original loss.

Early days of World War I

The plan’s core goal was to defeat the French Third Republic. At the same time, a smaller German force would move eastward to hold off any potential Russian threats until reinforcements could arrive. In 1914, the German Army, with a total strength of 1,191 battalions, directed most of its forces to the Western Front for the campaign against France, while the East Prussian Eighth Army, representing just 10 percent of Germany’s military, focused on the Eastern Front.

In response, France quickly mobilized, launching an immediate counterattack to push back the German advance. Neutral Belgium, after two weeks of combat in the Battle of Liège – the first official battle of WWI—yielded to the German forces, opening a strategic route for their invasion.

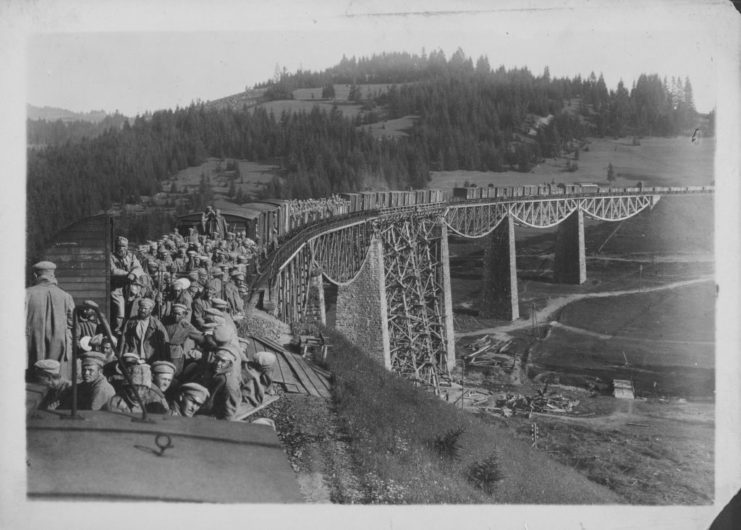

France counted on eventual support from the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and its Russian allies, recognizing that Russia would need time to fully mobilize. With a limited and largely single-tracked railway network (75 percent of Russia’s railways were single-track), it took approximately 60 days for Russia to position enough divisions to actively participate in the conflict.

Battle of Gumbinnen

Germany soon realized that two separate Russian armies were driving into East Prussia from different directions. Under pressure, von Prittwitz engaged the Russian 1st Army at Gumbinnen on August 20, 1914. The battle proved costly for both sides, but with a second Russian army closing in, he began contemplating a complete retreat—a prospect that horrified German leaders and was promptly rejected.

Confidence in his leadership evaporated, leading to von Prittwitz’s removal. His replacements—General der Infanterie Erich Ludendorff and the seasoned Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg—quickly took charge. Their arrival marked a pivotal shift, as they reorganized the Eighth Army and prepared to exploit Russian missteps, setting the stage for a dramatic reversal on the Eastern Front.

Was Russia doomed from the start?

Even before the first shots were fired at Tannenberg, the Russian Army’s prospects were compromised. Lacking experience with modern communications, Russian commanders made the grave error of sending orders over open radio frequencies. Although encrypted, the transmissions were easily captured by German forces, who exploited the information to devastating effect.

Surrounding the Second Army

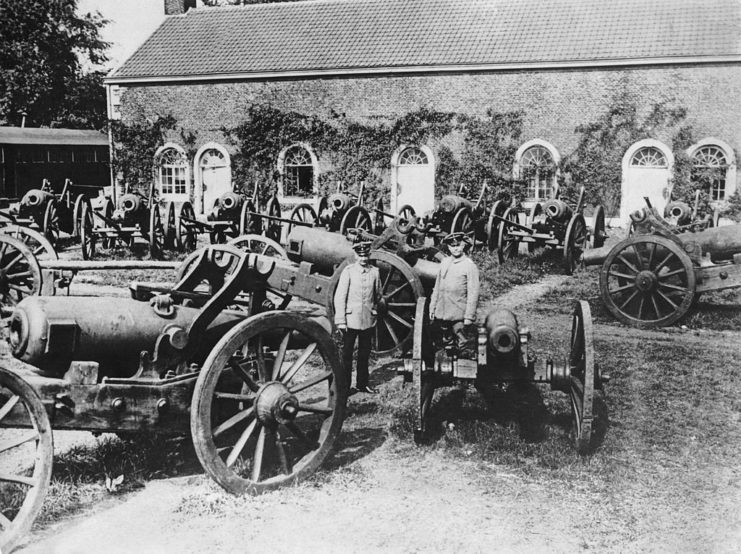

Using the intercepted radio messages, Ludendorff, a military theorist, came up with a strategy to attack the 2nd Army south of the Masurian Lakes. The 2nd’s commander, General of the Cavalry Alexander Samsonov, was already hindered by a slow supply chain, poor communication and the difficulty of navigating a large force with heavy artillery through the are’s impossible terrain. Soon, he and his men found themselves completely surrounded by the Germans.

“Imagine this Russian army as a bulge pressing into Germany and the Germans strike at a point where the bulge begins and cut off the vast majority of the Russian forces in the middle,” explains military historian, Jay Lockenour. “Because of communication problems, the Russian commanders didn’t know that a major attack on their flank was underway until half a day too late.”

Samsonov’s men were spread out over a 60-mile stretch, with the center, right and left wings separated – practically inviting the Germans to attack both wings. Meanwhile, the 1st Army Corps, led by General of the Cavalry Paul von Rennenkampf, was in no rush to come to the 2nd’s aid. Instead, a lapse in communication failed to urge him to pick up the pace and change his focus from Königsberg to the Masurian Lakes.

On August 26, 1914, Ludendorff ordered General der Infanterie Hermann von François and his I Corps to attack and break through the Russians’ left wing.

Who won the Battle of Tannenberg?

The climax of the Battle of Tannenberg unfolded on August 27, as German forces unleashed concentrated fire on the Russian left wing. Under intense pressure, Russian troops began a chaotic retreat toward the border near Neidenburg. Seizing the opportunity, General Hermann von François ordered his men to block the road from Neidenburg to Willenberg, effectively cutting off the fleeing soldiers.