Thousands of men served as officers in the British army during the First World War. Many of them lost their lives, and the survivors were changed forever. They do not appear in the grand narratives of the war, but in amongst the death and destruction, there are countless examples of inspiring men in the face of mortality.

Noel Hodgson

Fear was an inevitable part of life in the trenches. Troops coped with it in different ways. Many used words; writing poetry or letters back home.

On June 29, 1916, Lieutenant Noel Hodgson wrote a poem called “Before Action,” about the dangers he would face and the beauties of the world. He ended with the lines “By all delights that I shall miss, Help me to die, O Lord.”

Two days later, Hodgson went into battle at Mametz Wood. Overcoming the fear and the horror he had so eloquently explored in words, he faced the Germans. He was hit in the neck by a machine-gun bullet and died.

Guy Chapman

Second Lieutenant Guy Chapman was a great chronicler of the horrors of the war. In his writing, he recorded the loss of countless friends and comrades. He saw death in all its terrifying forms. A man’s head pierced by shrapnel. Another blown into a fine mist only feet away from Chapman. An officer who staggered back from an attack with his skin left charred and peeling by a flame thrower.

Chapman was affected by mustard gas. Fortunately for him, mustard gas was often an irritant rather than a lethal weapon, and he survived the experience.

In spite of all the horrors he saw, Chapman kept writing. He also kept fighting. On the Somme, he was twice selected to be one of the officers Left Out Of Battle (LOOB). The LOOB were 10% of a battalion’s numbers, left behind so that the unit could rebuild if the rest were killed or injured. Far from being relieved at avoiding danger, Chapman was upset to find he was left behind while his friends faced the hazards of battle. As he said goodbye to his company for the second time, he found himself unable to meet a man’s eyes.

Anthony Eden

A future Prime Minister, Eden entered the war as a young Second Lieutenant in the 21st Battalion of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. He fought in many significant battles of the war, including the Somme, Messines Ridge, and Third Ypres. Never one to shy away from the hazards his men had to face, he saw death and destruction, rescued wounded men and the bodies of fallen colleagues, and spent time stranded in the mud of no man’s land.

By 1917, Eden was a Captain and the only combatant officer to have been with the 21st Battalion since they entered the war. In 1918, he was made Brigade-Major of the 198th Infantry Brigade. Only 21 years old, he was the youngest officer to hold that rank on the Western Front.

Eden combined courage with humility. Like Chapman, he was disappointed to be included in a LOOB detachment at the Somme and protested to his colonel. He also protested on being appointed as adjutant by his commanding officer, claiming unworthiness for promotion.

Even after close brushes with death, Eden did not waver in doing his best. In October 1916, a piece of shrapnel tore the holster of his revolver and would have seriously injured or killed him if his weapon had not been on the wrong side. He continued to superstitiously wear it that way for the rest of the war.

G W S Foljambe

Eden was lucky in having an inspiring example to lead him. Major Foljambe, his commanding officer, was not a man to be rattled by combat.

On one occasion, a German 5.9” shell buried itself in the sandbag wall between the two men. Although a dud, it was frightening. Eden feared the situation was hopeless, and with shells falling so close they were in terrible trouble. Foljambe took the opposite view – that if they could survive such a close call, then they would get through the battle in one piece. He proved right.

On the Somme, Eden saw Foljambe’s firm words help a young officer shaken by battle, turning him into a man who showed strength and grace under fire.

Douglas Gillespie

A law student when the war broke out, Douglas Gillespie volunteered like many others. As an educated young man, he was made a second lieutenant.

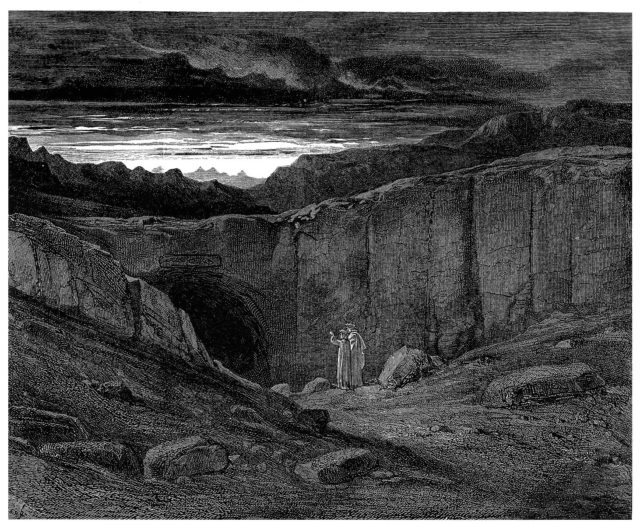

Amidst the mud and horror of the trenches, Gillespie was determined to keep his mind busy. He took copies of Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Dante’s Inferno with him to war, as much an omen of what was to come as they were sources of entertainment. He wrote home regularly to his parents, talking about his experiences in the trenches. Despite his circumstances, he found beauty in the moonlight across the countryside and the songs of the nightingales.

Although studious, Gillespie did not flinch from hard, dangerous work. He led a group of his men in a covert night-time expedition into no man’s land. There they cut samples from the German barbed wire and pulled up an example of the stakes holding it in place to provide intelligence on German defenses.

On April 25, 1915, Gillespie led a charge at Loos. He wrote the night before that he would take the lead not because he was special but simply because someone had to. With quiet courage, he led his men from the front straight into battle.

Gillespie died leading that charge. His letters, like those of many others, provide a striking example of the courage of men in that most dreadful war.

Sources:

John Lewis-Stempel (2010), Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War.