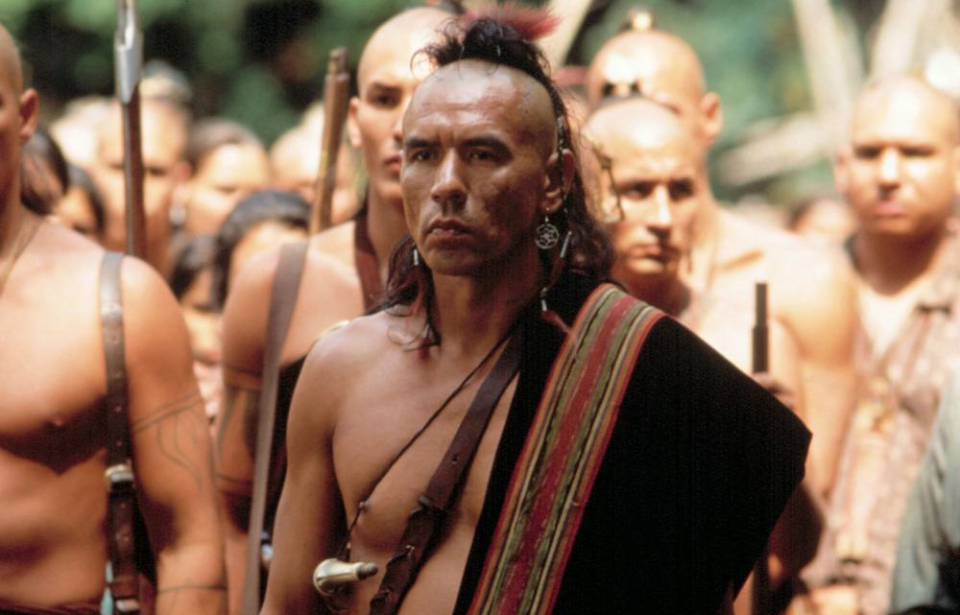

Wes Studi is highly regarded for his powerful, deeply authentic performances in films such as Dances with Wolves, The Last of the Mohicans, Geronimo: An American Legend, and The New World. Through his nuanced portrayals of Native American characters, he has earned lasting acclaim and a reputation for bringing dignity, depth, and realism to roles that were long mishandled in Hollywood.

Before his acting career began, Studi lived a very different chapter of his life. He enlisted in the Oklahoma National Guard and was deployed to Vietnam, where he confronted the brutal realities of war firsthand. The discipline, resilience, and perspective forged during his military service later carried into his work as an actor, lending his performances a quiet authority and emotional authenticity shaped by experiences far removed from the world of film.

Wes Studi’s early life

Wes Studi was born in Nofire Hollow, Oklahoma, and grew up in a Cherokee-speaking household, only learning English when he began attending elementary school. He later enrolled at the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, a federally run boarding school where he graduated in 1964. At Chilocco, students were required to pick a trade for vocational training, and Studi chose dry cleaning as his specialty.

At the age of 17, Wes Studi enlisted in the Oklahoma National Guard, committing to the standard six-year term of service that was customary during that era. In an interview with Military.com, he shared that his reason for enlisting was that he “got to march around our school grounds and had a paycheck as well.”

Wes Studi is deployed to Vietnam

While serving with the Oklahoma National Guard, Wes Studi underwent both basic combat and advanced individual training at Fort Polk, Louisiana. During his time there, he decided he wanted to serve in the Vietnam War after hearing stories from those who had recently returned. With only one year left in the National Guard, he volunteered for active duty.

Studi was deployed overseas with A Company, 3rd Battalion, 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, serving with them for 12 months. He later recalled arriving in Vietnam just before the “Mini-Tet” Offensive, when the Viet Cong and Northern Vietnamese Army (NVA) launched an attack on Saigon following the Tet Offensive.

He shared with Military.com, “I actually didn’t partake [in] all of the fighting that was going on there in Saigon. I think they decided to leave most of us who were new in country there at the French Fort, even though the company was very active in the defense of Saigon at the time.”

The fort, situated near the Mekong Delta, was where most of the 9th Infantry Division’s missions were carried out. Located deep in Viet Cong-controlled territory, they spent much of their time defending the area against enemy forces.

Returning stateside

Like countless Vietnam veterans, Wes Studi faced significant challenges when transitioning back to civilian life. His time in combat had instilled a constant sense of vigilance—an instinct that didn’t simply disappear once he was home. Adding to that difficulty was the widespread public resentment many veterans encountered during that era. Instead of receiving a hero’s welcome, Studi, like many of his peers, returned to a country that often met him with negative attitudes and hostility. Reflecting on that time, he once said, “When I came back, I had to deal with being called a baby killer, with how soldiers were treated when they returned from there.”

During this difficult time, Wes Studi discovered new meaning through two powerful pursuits: activism and acting. Driven by his experiences as a Vietnam veteran, he became involved with Vietnam Veterans Against the War, an influential group established in 1967 that empowered returning soldiers to speak out against U.S. involvement in Vietnam. This organization played a key role in shaping the anti-war movement of the period.

In 1973, Studi’s commitment to activism intensified when he participated in the 71-day Wounded Knee Occupation—a protest that honored the historical Massacre at Wounded Knee of the Lakota people and highlighted ongoing Native American struggles for justice. Concurrently, he began to explore acting, enrolling at Tulsa Community College, a decision that would eventually lead him to a celebrated career in film.

Wes Studi’s decades-spanning acting career

Early in his acting career, Wes Studi often appeared in small, sometimes uncredited roles, gradually working his way into the industry. As his presence grew, he became part of a broader shift in Hollywood—one in which Native American characters were finally written with greater depth, complexity, and humanity, moving beyond the flat stereotypes that had dominated for decades.

Over time, Studi expanded his range across both film and television, delivering performances that were consistently powerful and grounded. His contributions to cinema and his lasting cultural impact were formally recognized in 2019, when he received an Academy Honorary Award—making history as the first Native American actor to be awarded one of the Academy’s highest honors.

Wes Studi’s service in Vietnam left a deep and lasting imprint on his work as an actor, profoundly shaping the emotional truth he brought to his performances. Drawing on his firsthand experience of war, he infused his characters with a realism and gravity that few could convincingly replicate. In a 2017 GQ interview, Studi reflected on his role as Chief Yellow Hawk in Hostiles, explaining that the gradual evolution of the relationship between his character and Christian Bale’s Captain Joseph J. Blocker mirrored his own shifting perspective during the war—moving from viewing the Viet Cong solely as enemies to recognizing their shared humanity amid the brutality of conflict.

He said, “I have a great respect for the Viet Cong, not only because of their prowess and their ability to fight… But I have a great respect for them, not only because they’re great warriors. They’re probably more like me than the people I was fighting for, you know? I think that was sort of what fed the kind of feelings that existed between Yellow Hawk and Bale’s character.”

Veteran activism

More from us: Before Becoming An Actor, Adam Driver Served in the US Marine Corps

Studi believes that spirit of mutual care should extend well beyond the battlefield. “War may be hell—but peace can be a killer, too,” he noted. “It is absolutely incumbent on the nation to take care of our veterans. Interventions – be it counseling or acting or farming or anything else – need to get out ahead of the pain and tragedies.”