Arrogance. Ignorance. Poor planning. These were the weapons with which French commanders fought the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, and with which they ensured their own defeat. Their hubris and incompetence in this battle, fought from March to May 1954, ensured outright defeat in the First Indochina War, giving victory to the Viet Minh revolutionaries and independence to Vietnam.

1. Treating Their Enemies as Ignorant Peasants

The French attitude towards the Vietnamese soldiers, buoyed up by the same attitude from American advisors, was one of contempt. Trained in the tactics and attitudes of western European military academies, they believed in the total superiority of European and American ways of war. To them, the Vietnamese troops were backwards and poorly trained, easy to defeat.

In reality, many of the Vietnamese were skilled and experienced, but in different ways from their western opponents. They understood how to fight in their own country, not just how to fight in a textbook European style.

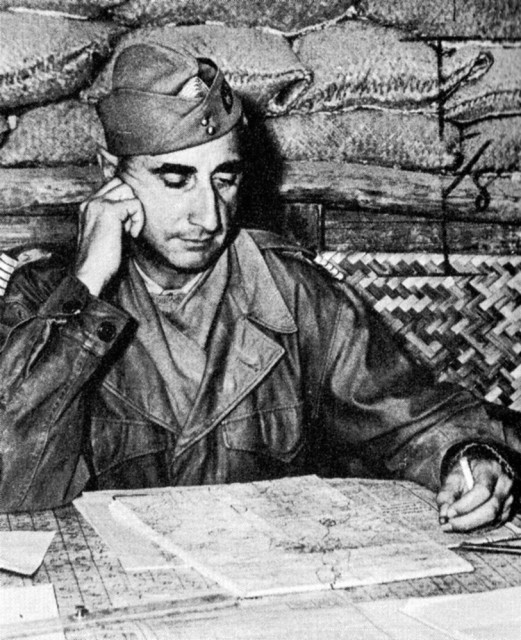

2. Underestimating General Võ Nguyên Giáp

The Vietnamese at Dien Bien Phu were led by General Võ Nguyên Giáp. A skilled and experienced commander, Giáp had led Vietnamese troops during their resistance against the Japanese occupation during World War Two. A dedicated Communist since his teens and a capable politician as well as a commander, by 1954 he was Vietnamese Minister of Defence as well as one of the leading lights of the war effort.

General Giáp was one of Vietnam’s greatest ever strategists, but in the eyes of the French, he was just one more unskilled Vietnamese soldier. General Salan referred to him as “a non-commissioned officer learning to handle regiments”. As a result, the French badly under-estimated the skill with which the Vietnamese forces would be led.

3. Political Ignorance

The political landscape in East Asia had changed since the start of the war. The Korean War was over, freeing up the Chinese to send more resources to Vietnam to support their Communist allies. Stalin’s death had thawed Russia’s attitude towards the west, and the Soviets now leaned more towards peaceful settlements of the region’s conflicts to improve their foreign relations. The French public was growing sick of the fighting, and politicians were ready to bend to the popular view. As a result, the French government was looking for a position from which to negotiate a favourable peace, rather than to continue the war in search of outright victory. They wanted out before Chinese resources turned the tide fully against them.

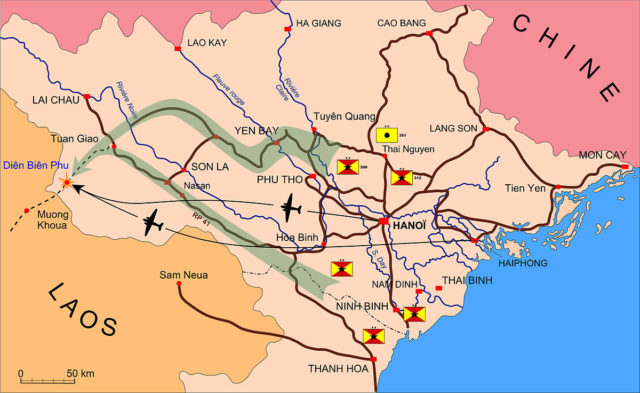

Unfortunately General Henri Navarre, the new French commander in Vietnam, believed that he could achieve victory. By focusing French resources at Dien Bien Phu, he sought to force Giáp to attack him. This, he believed, would allow him to win a crushing victory. And so, against the policies of the French government, he launched a perilous plan.

4.A Surrounded Position

Navarre’s choice of Dien Bien Phu as a place to force Giáp to battle was a terrible one. Deep in the hills of northwest Vietnam, the position was surrounded by high ground. 14,000 troops were inserted in March, and almost immediately surrounded by superior numbers of Vietnamese soldiers. The Vietnamese cut of French supply lines and besieged the encampment. While the French struggled to provide supplies by air, their engineers rushing out to repair the runway between bombardments, the Vietnamese were supported by friendly locals and short supply lines.

The French had walked themselves into a trap.

5. Underestimating the Potential of Guerrilla Warfare

At Dien Bien Phu, the French made the same mistake that western armed forces would repeatedly make throughout the latter half of the 20th century – they underestimated the potential of guerrilla fighters.

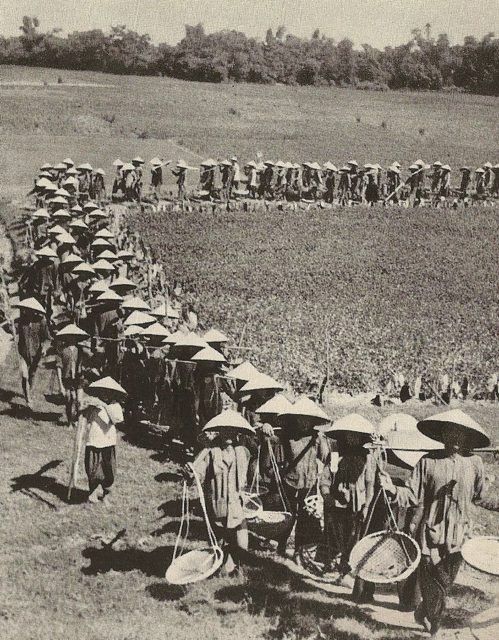

In this case, guerrilla warfare did not just mean hit and run attacks by ragged bands of infantry. After all, this was a siege. But the Vietnamese used guerrilla techniques to bring the full weight of their military to bear. Supplies and artillery were carried onto the high ground by humans, animals and even bicycles bought from French suppliers prior to the war. By the time they were all in place, the Vietnamese had four times as many soldiers present as the French, and were pounding them mercilessly with artillery that Navarre had believed could not possibly be brought to bear.

6. Assuming Their Enemies Would Not Learn

In earlier phases of the war, the Vietnamese had relied on throwing waves of mass infantry against the French. It was a tactic that had been used heavily by the Japanese during the Second World War and was also a favourite of Vietnam’s greatest sponsor, Communist China.

The French plan relied on the Vietnamese using these tactics against, wasting the human resources in massive assaults on better equipped French positions. But Giáp had learned his lesson. There would be no endless waves of men charging forth to death or glory. Steady bombardment and the strangling effect of the siege took their place.

7.Relying on Tanks

Another cornerstone of the French plan was their own tanks, but the terrain was completely unsuitable for this. The land was thickly covered with bushes, which entangled and debilitated the tanks. There would be none of the advances over open ground they had expected. Heavy rain soaked the ground, further bogging down the French armour.

8. The Wrong Officers for the Job

To cap it all off, Navarre chose leaders for the expedition deeply tied to the French plan and outlook, and therefore deeply unsuited to the reality of the battle. The commander, Colonel Christina Marie Ferdinand de Castries, was a brilliant tank commander whose potential was entirely wasted in terrain where his vehicles could barely move. His deputy, the artillery commander Colonel Charles Piroth, was one of those who believed in the inherent inferiority of the Vietnamese. Finding himself proven horribly wrong, and completely incapable of effectively striking the Vietnamese dug in on high ground, he committed suicide using a hand grenade.