There have been a number of times when fashion outweighed function when it came to military uniforms, sometimes leading to deadly results. The shortfalls that occurred were oftentimes known, but, in some instances, the issues plaguing them were a total mystery. Below, we explore six uniform elements that caused many servicemen to perish while on the battlefield.

Neck stock

The neck stock was a removable component of European soldiers’ uniforms during the 18th and 19th centuries. They were made of horsehair, whalebone or stiff leather, and wrapped around the neck and under the chin. Its ability to be easily replaced deemed it a suitable addition to uniforms, and the piece’s stiffness forced a soldier’s chin up, improving his posture.

Unfortunately, the stiffness of the neck stock was also its demise. It dug into a soldier’s neck and chin, making it uncomfortable. As well, it caused a loss of agility and awareness, and made it near impossible to look down the sight of a musket – all of which are things you don’t want to have happen in the middle of battle.

Due to this, the neck stock was among the most deadly aspects of a soldier’s military uniform and was subsequently discontinued.

White bands

Adding a white band to a uniform had its benefits and drawbacks. On one hand, it served as a visual marker that made the wearer stand out, aiding in identification and cohesion within a unit. However, this was also the issue, as it made the soldiers wearing the implement walking targets.

Throughout history, the British Army frequently featured white bands on its uniforms. During the 18th and 19th centuries, these bands adorned soldiers’ iconic red coats (which we discuss later), inadvertently providing enemy snipers with a clear target. Even with the evolution of military wear during the First World War, similar oversights remained.

For instance, during the Gallipoli Campaign, British troops wore white armbands to facilitate identification among comrades. However, this well-intentioned measure backfired, as it made them easy targets for the Turkish forces, particularly when they stood in exposed positions along beaches.

Hessian headgear

Hessians were German soldiers hired by the British as an auxiliary force during the American Revolution. Even though they fought alongside the British, who traditionally wore read coats, they wore their traditional uniforms, including tall headgear adorned with medals.

Although these helped to distinguish the Hessians from the British, they also drew a lot of attention. Gold and silver plates positioned along the fronts of the headpieces were easily spotted by American soldiers, and their height often caused them to catch on tree branches. While the latter was more of an inconvenience than anything, the former could prove deadly.

Red coats

British soldiers during the US Revolutionary War could be easily identified by their bright red coats, which they wore as a part of their uniform (hence the nickname, “Redcoats”). The hue helped comrades identify each other through the smoke of gunfire and was believed to make the British look intimidating, complimenting their perceived power.

While their red military uniforms made it easier for soldiers to identify friend from foe, they also made the British easier to spot, which proved deadly during encounters with the Continental Army. They were unable to hide or launch surprise attacks, and the coats themselves were made of a heavy wool material, which was both itchy and uncomfortable.

Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP)

While the most recognizable uniform design for the US Army as of recent decades, the adoption of the Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP) proved to be the wrong choice. Introduced in 2005 after laboratory tests, the design aimed to provide soldiers adequate camouflage in a variety of terrains, from forests to desert sands. However, it failed to do this.

The pixelated hues failed to blend as seamlessly as the Army had hoped, meaning that, in the majority of combat environments, troops were typically vulnerable to detection by enemy forces. Not only did this greatly compromise the element of surprise, but there was an increased risk to the lives of service members in combat, as they couldn’t easily hide from enemy fire.

Given these issues and the amount of complaints coming from soldiers, the Army announced in 2014 that it would be replacing the UCP with the Operation Camouflage Pattern (OCP), which is currently issued.

Cardboard shoes

Wartime often means rationing, with supplies becoming tight as they’re allocated for use in the war effort. When the necessary items run out altogether, adjustments have to be made. That’s how cardboard shoes came to be issued to soldiers in Napoleon Bonaparte‘s Grande Armée.

To make up for the lack of supplies needed to produce service boots, the French soldiers were supplied with faux leather boots with cardboard soles used in place of real leather. Not only impractical, this part of their military uniform was also deadly, as the shoes weren’t properly insulated, leading to severe cases of frostbite in the freezing outdoor temperatures.

Tin buttons

Depending on who you ask, tin buttons may have played an unexpected, yet significant role in Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat in 1812, during the French Army’s Russian Campaign. As temperatures plummeted during the harsh Russian winter, the French soldiers faced a dire shortage of essential supplies, including adequate clothing and provisions. Compounding this was the tin buttons that adorned their uniforms.

Unlike brass or other metals, tin quickly loses its structural integrity in extreme cold, thanks to its two primary allotropes, beta-tin and alpha-tin. The latter is known for being brittle, while the former is particularly sensitive to temperatures below 56°F. In fact, it’s so sensitive that such cold turns it into alpha-tin, meaning the tin buttons on the French Army’s uniforms disintegrated, leaving the men vulnerable to the biting cold.

It should be noted that historians have varying opinions as to how much of a factor this was to the defeat of Napoleon’s forces in Russia, but, regardless, such a uniform feature couldn’t have helped matters.

World War I-era headgear

Upon the outbreak of the First World War, the idea of death by shrapnel was far from anticipated. Unaware of what they would encounter during the trench warfare that came to define the fighting on the Western Front, British soldiers were deployed with soft caps. While the trenches could protect them from enemy gunfire, the caps they wore did virtually nothing to protect against shrapnel.

It only took one year for Britain’s War Office to develop a new type of military headgear that’d reduce the amount of head injuries suffered in combat. The “Brodie” helmet was the soft cap’s replacement, and soldiers began receiving it in the summer of 1916. While made of steel, it still wasn’t the safest, as it left a soldier’s neck and the lower portion of the head exposed. As well, the metal reflected light, which played tricks on the eye.

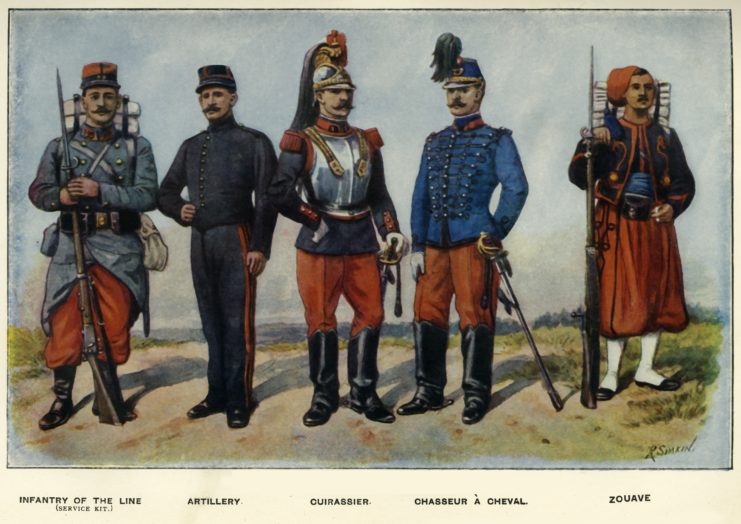

Le Pantalon Rouge

The French Army had worn red pants as early as 1829, and while a number of countries had abandoned the color in favor of something less distinguishable, the French continued to don their red attire up until 1914.

When World War I began, the French Army suffered numerous casualties, as troops were unable to mount surprise attacks or hide with their bright red pants, which stuck out against the mud of the battlefield. When Minister of War Adolphe Messimy suggested that the trousers were the problem, he was met with intense resistance.

More from us: The Most Dangerous Aircraft to Ever Take to the Skies

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

It took thousands more deadly encounters for the military to change up its uniform and allow soldiers to wear blue bottoms.