One of the most important tools of the Roman army, the blockade camp, was classic Roman engineering under fire.

What Was a Blockade Camp?

On arriving anywhere for the night, it was normal for the Roman legions to build a temporary fortified camp. During sieges, these were more substantial, providing the legions with shelter from attacks by defenders or relief forces.

A blockade camp did not surround the besieged town or fortification. Circumvallation, far larger siege works, served this role.

The blockade camp was one or more fortified points which served three roles:

- Preventing resupply and reinforcement.

- Deterring sorties.

- Providing a garrison for the besiegers.

Concentrating Force

Any besieging army had to set up camp somewhere. The distinctive Roman camp, with its many functions, is reported as early as the 7th century BC and was a regular feature of war by the 4th century.

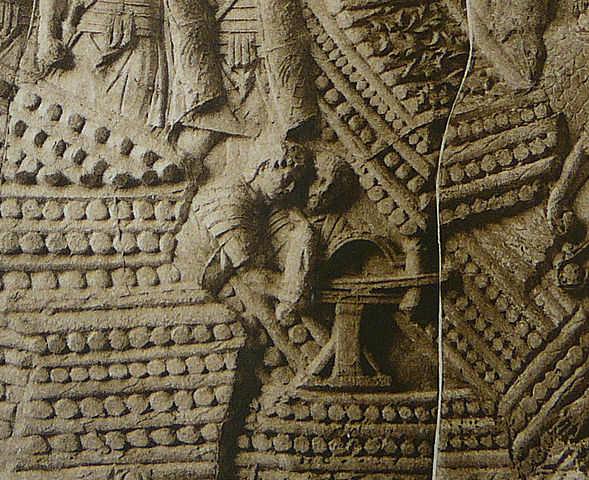

As Rome expanded, war became more complex and protracted. At Veii (405-396 BC) the Romans chose to remain through the winter rather than return home after the campaign season. The siege was a serious undertaking and was built to reflect this. One main fixed fort referred to as a castra, held the most important position, accompanied by smaller satellite forts, or castella.

Although these blockade camps did not completely cut off the defenders, they were often enough to contain them and block their supplies. By concentrating the besieging forces, they made the Romans more secure from a counter-attack, leading Marcellus to abandon a more spread out approach at Syracuse (214-212 BC).

Using the Terrain

Skillful commanders made use of the local terrain when choosing a site for their siege camps.

At Carthago Nova (210 BC)), Publius Scipio did not take the obvious position on an isthmus 250 paces wide. Instead, he camped on raised ground overlooking the isthmus. This gave him a better defensive position and the flexibility to fight on the open ground nearby while retaining control over the isthmus.

As blockade camps required fewer resources to build, they remained in use after the development of circumvallation; provided the terrain was right.

Scipio Aemilianus at Carthage (147 BC) and Julius Caesar at Avaricum (52 BC) set up camp on narrow stretches of dry land that blocked the way out. Rough terrain protected their flanks, therefore a small number of men could contain the enemy.

The Building Process

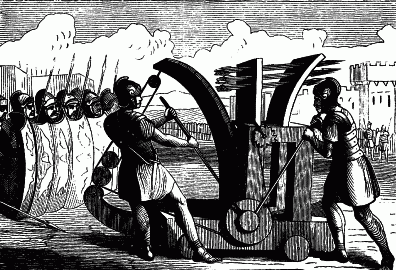

Constructing a blockade camp could be dangerous. They were frequently built close to enemy walls to apply the most pressure. This meant the construction crews could come under fire from missiles, as at Massilia in 49 BC, or become the target of a sudden sortie by the defenders.

Building them was back-breaking work, but the legionaries were used to it. Using construction equipment they always carried with them, they dug ditches, raised ramparts, and placed spikes. The work could easily take weeks, during which time half the army would labor while the other half defended them.

Strong Points

The focus of any blockade camp was its strongest point – the main fort or forts. They provided the main camp for troops to sleep in, the central base of operations, and the best defensive point to fall back to if other areas fell.

The value of having a single identifiable strong point is demonstrated at Veii in 402 BC. A combination of relief forces and defenders coming out of the city overwhelmed much of the Roman siege system. The smaller of two castra fell, along with all the smaller bases. By retreating to their largest garrison base, the Romans were able to hold on, maintain their presence, and later retake the whole blockade system.

Connecting Works

The establishment of separate camps risked leaving the Romans divided and more easily defeated. To counter this, they began to set up entrenchments and garrison posts connecting the camps together.

Connecting works became a regular feature from the sieges of Agrigentum (262 BC) and Lilybeaum (250-241 BC) onwards. These were sometimes sophisticated works, as at Gergovia in 52 BC, when Caesar had a substantial double ditch dug connecting two fortified points.

Detached Forts

Some fortifications were left separate from these connecting systems. Most notable were detached forts well away from the main siege lines and the town they threatened.

Positions like these were built at Thapsus (46 BC), Ategua (45 BC), and possibly Bethar (135 AD). The troops in them could not take part in attacks on the town, but they could intercept an advance by enemy relief forces. At Thapsus, this held off Scipio long enough for Caesar to complete his main camp.

Aggressive Defences

The techniques used in building blockade camps make them look like defensive structures. In one sense they were, as they protected besiegers. However, to call them defenses distracts from the aggressive function they served.

If Roman commanders had only been interested in keeping their men safe, they could have built blockade camps well back from city walls. Instead, they pushed them forward to within arrow shot of the enemy, putting their men at risk as they built.

Driving blockade camps forward turned defensive structures into tools of aggression. Siege weapons and missile troops could sit safely within these lines while bombarding their enemy. Attack ramps could be extended from them. Surprise assaults could be launched. All the while, the defenders were kept aware of their precarious position by the sight and sound of the troops beyond their walls.

Blockade camps piled on the pressure.

Fading into History

Over time, circumvallation took over from the blockade camps as the usual Roman approach to siege craft. Then another change took place, with a shift away from protracted sieges in favor of direct assaults.

By Bezabde (360 AD) and Maiozamalcha (363 AD), the construction of fortified siege works had become unusual enough that it was considered noteworthy by chroniclers. Roman blockade camps faded into the past along with their empire, to be rediscovered by historians and archaeologists centuries later.