Operation Downfall

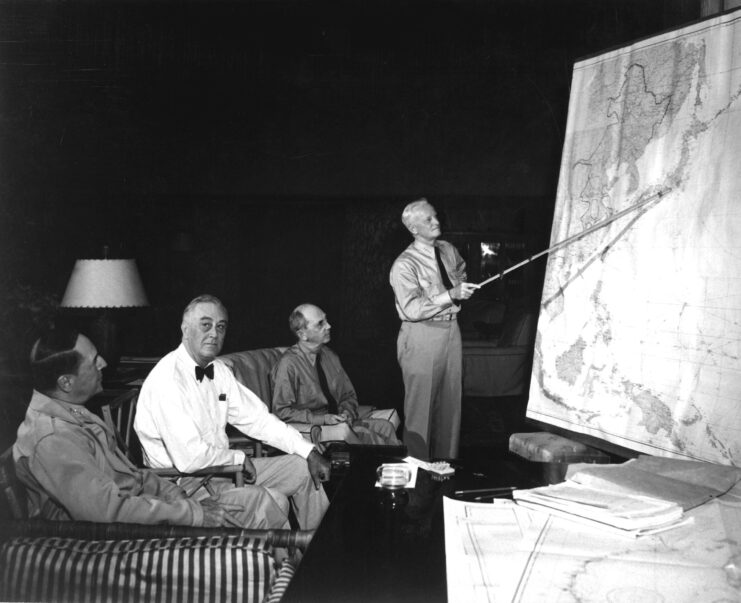

Operation Downfall was the U.S. military’s detailed plan to invade and defeat Japan, and it was set to be the largest amphibious invasion in history—surpassing even D-Day. The plan had two main parts: Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet.

Olympic was scheduled to launch in November 1945, targeting the southern island of Kyūshū. Once captured, Kyūshū would be used as a base to support Coronet, the second and even larger phase. Coronet was planned for March 1946 and aimed to invade the Tokyo Plain.

The invasion never happened. Japan surrendered after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, along with the Soviet Union’s declaration of war. As a result, the U.S. called off Operation Downfall, avoiding what likely would have been a devastating loss of life on both sides.

Training kamikaze frogmen

In preparation for the looming Allied invasion, Japan devised a desperate defensive measure known as the Fukuryu, or “crouching dragon.” This strategy relied on divers who were specially trained to carry out stealthy underwater assaults against approaching enemy vessels.

The concept was first proposed in 1944 by Captain Kiichi Shintani of the Anti-Submarine School at the Yokosuka Naval Base. With Japan’s conventional defenses crumbling due to shortages of manpower and resources, Shintani looked to earlier hard-fought battles—such as Peleliu—for inspiration.

Fukuryu teams were stationed along key stretches of the Japanese coastline, lying in wait beneath the water. Under the cover of darkness, they aimed to detonate explosives against enemy ships. Their concealed movement beneath the waves made them difficult to detect, presenting a dangerous and unnerving challenge for any invading force.

Fukuryu attacks

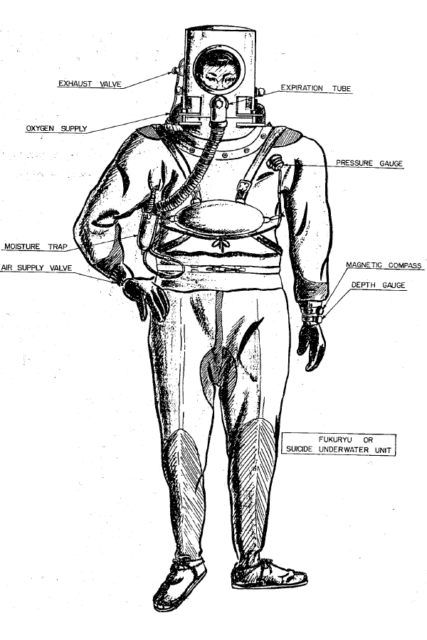

In Japan’s last-ditch efforts to repel an invasion, specially trained kamikaze frogmen were prepared for stealthy underwater attacks against Allied ships. Wearing diving gear, they wielded 16-foot bamboo spears tipped with Type 5 contact mines that were packed with 33 pounds of explosives and engineered to detonate the instant they struck a target.

Staging areas were often supplied with extra explosives to increase the destructive effect. These missions were explicitly one-way operations, with no expectation of survival. The frogmen would lie submerged for hours, motionless and silent, fully conscious that the success of their task required their own deaths at the moment the mine detonated.

Training the kamikaze frogmen

Extensive preparations were made to train train 6,000 kamikaze frogmen, each requiring specialized equipment. They were to wear full diving suits—jacket, pants, shoes, and helmet—and carry oxygen supplies and liquid food to survive about 10 hours underwater. To stay submerged at depths of 16 to 23 feet, each man also carried 20 pounds of lead to fight buoyancy.

Beyond equipping the divers, Japan planned to build hidden underwater shelters where they could lie in wait for enemy ships. One idea was to build large concrete structures on land and later sink them into place, but this plan was never carried out. Another idea involved steel underwater foxholes, but it was quickly scrapped due to the risk of disturbing nearby explosives.

Even with all the detailed planning, Japan’s kamikaze frogmen were never actually used in combat.

A failed initiative

The 71st Arashi unit trained at Yokosuka, while the 81st Arashi began their instruction at Kure. A third unit was planned for Sasebo, but progress stalled. By the time Japan surrendered, only two battalions—both from the 71st—had completed their training, totaling roughly 1,200 of the proposed 6,000 men.

Training delays weren’t the only problem. Equipment production lagged behind as well. At surrender, just 1,000 diving suits had been manufactured, and none of the actual explosive mines had been built—only practice versions existed.

Although the Fukuryu divers were never deployed in combat, the training process proved deadly. Many recruits lost their lives due to faulty breathing systems. The crude gear required divers to inhale through their nose and exhale through their mouth into a canister meant to recycle the air. A simple mistake in this process caused them to breathe in caustic lye and lose consciousness underwater. If seawater seeped into the apparatus, it created a chemical reaction that severely burned the lungs when inhaled.

Some divers also drowned after becoming entangled in underwater vegetation and being unable to escape. In the end, no enemy forces were harmed by Fukuryu operations, but so many trainees died during preparation that, reportedly, “they couldn’t keep up with cremation.”