26th Cavalry Regiment (Philippine Scouts)

The 26th Cavalry Regiment dated back to 1901, when the US Army first inducted Filipinos into its ranks, “to help restore order and peace to a troubled area.” Fast forward to a few years after World War I, when they were officially inducted into the regular US Army. By this time, there were 6,000 members across two infantry regiments and other divisional elements, all stationed in the Philippines.

As Japan’s territorial expansion became more aggressive in the lead up to the Second World War, the US Army established the 91st and 92nd Artillery Regiments, to ensure Manila Bay could be defended in the event of an invasion.

At the outbreak of the conflict, the 26th was considerably smaller than regiments stationed in the United States. It consisted of just 784 enlisted men and 54 officers.

Delaying the Japanese advance

A key element of World War II was Japan’s aggressive expansion across the Southeast Pacific, turning entire nations—including the Philippines—into strategic flashpoints in the conflict.

By January 3, 1942, the Imperial Japanese Army’s Fourteenth Area Army had taken control of Manila and was closing in fast, threatening to prevent the retreat of Lt. Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s forces before they could fall back to the Bataan Peninsula. Though outgunned and outnumbered, the 26th Cavalry Regiment—already known for its discipline and resolve—was tasked with a critical objective: delay the enemy long enough for American and Filipino troops to regroup and reinforce Bataan’s defenses.

Cavalrymen charge into battle

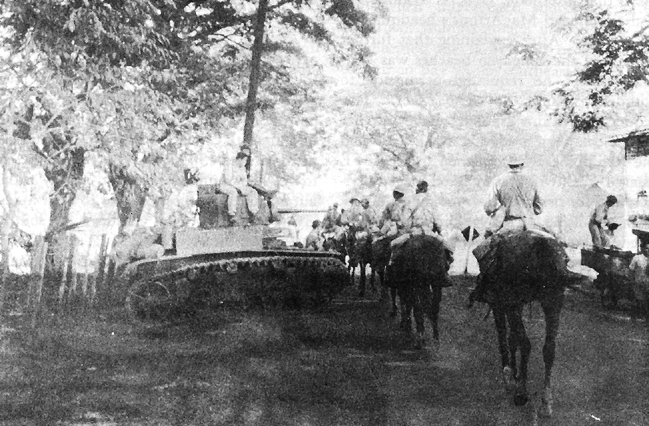

On January 16, 1942, Lt. Edwin P. Ramsey, a platoon commanding officer who’d volunteered to join the 26th Cavalry Regiment in ’41, led men from E and F Troops into Morong (then Moron). While their opponents were equipped with tanks and machine guns, the 27 American and Filipino cavalrymen had only their pistols and the horses upon which they were riding.

The Japanese troops stationed in the village were caught off-guard by the sight and scattered as the American and Filipino troops, pistols drawn, galloped toward them at full speed. “To them, we must have seemed a vision from another century,” Ramsey would later recall. “Wild-eyed horses pounding headlong, cheering, whooping men firing from the saddles.”

Despite the Japanese being better equipped, the 26th successfully delayed their advance, suffering just three casualties in the process.

A transition to modern warfare techniques

Sadly, the 26th Cavalry Regiment and their horses weren’t able to celebrate their success for long. As supplied dwindled, the men were forced to do the unthinkable: butcher their trusty steeds for food. Following the cavalry charge, the 26th reorganized into a motorized rifle squadron and a mechanized regiment. The US military, like other armed forces at the time, was beginning to focus on modern warfare techniques and strategies.

The 26th was deactivated in 1946 and disbanded in ’51. Over the course of its existence, it received three Presidential Unit Citations and one Philippine Presidential Unit Citation.

More from us: The P-47 Thunderbolt Pilot Who Was Escorted to Safety By Two Luftwaffe Fighters

As for Edwin P. Ramsey, he was awarded the Silver Star for his action at Morong. He subsequently found himself stranded on the Philippines following the American surrender, prompting him to go underground and work for the Filipino resistance. Following the war, Douglas MacArthur estimated the Ramsey’s guerrilla activities saved tens of thousand of Allied lives.