The name Rolex is often associated with luxurious wristwatches, synonymous with impeccable quality and style – and with a price to match.

While all this stands today, during WWII, the Rolex Company openly showed its support to the Allied cause, practically giving away their state-of-the-art watches to officers who had been captured by the Germans and were POWs.

The Rolex Company was founded in 1905 by a German, Hans Wilsdorf, and an Englishman, Alfred Davis. It was first based in London, but in 1919, Rolex moved to Geneva Switzerland, where they continued to manufacture watches. They are still in Geneva today, producing around 2,000 luxurious watches per year.

Switzerland withheld open support for any of the warring sides, due to its long tradition of neutrality. Swiss watchmakers became cautious of selling their products to either Allied or Axis governments in case they would be used for military purposes.

Hans Wilsdorf of Rolex, on the other hand, was a committed supporter of the British cause and an outspoken advocate of the anti-Hitler alliance. He was not going to follow the neutrality stand, as he felt that even a symbolic act could benefit the cause in such dire times.

After the Battle of Britain, Rolex became popular among RAF officers, who purchased the innovative “Air” models to replace their standard-issue Royal Air Force watches. The Swiss-made timepiece was more reliable, and it was offered at a reasonable price. The line was created to pay tribute to the brave airmen who managed to defend the skies above Britain when odds had not been on their side.

They produced models such as “Air-Tiger, Air-Giant, Air-Lion” and “Air-King.” They were slightly larger than their government-issued counterparts, making them more suitable for pilots whose life often depended on a split second. A wristwatch was indeed crucial during aerial operations and dogfights, as the necessity of knowing the time could decide the outcome of an attack, and therefore the fate of the pilot.

But Wilsdorf wanted to expand his support towards the fighting men of the Allied coalition even further. He became aware that the Germans were confiscating the watches of captured RAF men. He started a campaign of sending replacement timepieces to POWs. The Geneva Convention ensured that prisoners of war had the right to receive mail and packages via the Red Cross, so Wilsdorf encouraged the captured servicemen to write to him so he could send them a new Rolex watch.

The deal was that the watch would be paid for after the war when Europe was freed from Nazi rule. That way, he gave the POWs hope, in clearly stating that the war was going to end in their favor. Although, bear in mind, that Rolex watches were quite affordable at the time.

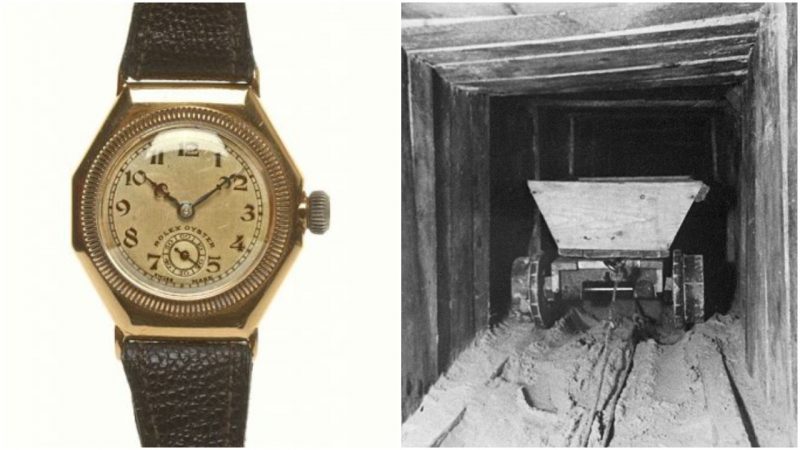

One such watch ended up in the hands of Corporal Clive James Nutting, one of the masterminds of the famous great escape from Stalag Luft III POW camp. On March 10, 1943, Nutting ordered a stainless steel Rolex Oyster 3525 Chronograph, which was pricey, even then. The request was sent directly to Hans Wilsdorf in Geneva, with an explanation that he would pay for the watch with money he had saved working as a shoemaker at the camp.

The watch arrived precisely four months later, on July 10, accompanied by a letter written by the Company’s owner himself. He apologized for being late with the delivery and wished the best of luck to the captive corporal, stating that an English gentleman such as Clive Nutting should not even think about paying for the watch before the end of the war. Allegedly, Wilsdorf, a man of exquisite taste, was impressed by the corporal’s decision to order the Oyster Chronograph, which was far more expensive than the other models popular among his fellow soldiers and officers.

Unbeknownst to him, Nutting had ordered the specific model because of the chronograph, or stopwatch, which came in handy while measuring the frequency of German patrols in the camp. Unfortunately, the daring escape from Stalag Luft III turned out to be a failure, with most of the escapees, including Nutting, back in their cells soon after. Some met a far worse fate when they were eventually captured as they were executed by the Gestapo, which was a clear breach of the Geneva Convention. Three of the men managed to escape to neutral Sweden and Spain.

After the war, Nutting returned to England and received a bill for his wartime Rolex. Due to currency export controls in England, he was charged a mere £15. The story of the watch which had participated in the great escape was popularized even more in 2007 when both the Oyster Chronograph and the correspondence between Wilsdorf and Nutting were sold at auction for the staggering price of £66,000.

As for Wilsdorf, his approach towards Allied soldiers and officers garnered him much respect, with more than 3,000 watches ordered during the war by POWs in Bavaria alone.

It was also a tremendous marketing strategy. When American soldiers stationed in Europe learned about the wristwatches from their British allies, they followed their example, and Rolex found a new market across the Atlantic Ocean.