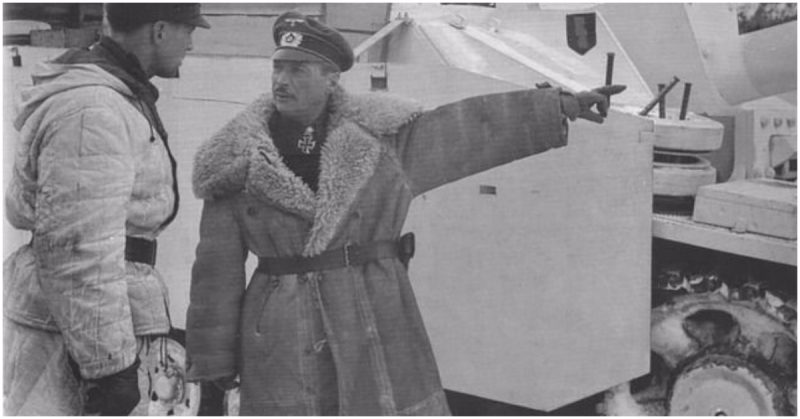

General Hyazinth von Strachwitz, known as the Panzer Count, earned a reputation for boldness as a cavalry officer in WWI. Then, during WWII he obtained both his nickname and his legendary status as a tank commander.

First World War

At the start of WWI, cavalry was still used to scout out enemy positions. Strachwitz, a 21-year-old lieutenant in the Guards Cavalry Corps, volunteered for a dangerous long-range patrol. With 16 hand-picked men, he swept around behind the French army, gathered information, cut telegraph lines, and blew up rail tracks.

For six weeks, Strachwitz and his men roamed France. Fear stirred in Paris at his attacks and troops were diverted to hunt him down. After several close run-ins, he and his men were eventually captured, tried as spies, and almost faced the death penalty.

Late in the war, Strachwitz escaped from a prisoner of war camp. He fell and was severely injured while trying to cross the Alps into Switzerland. He had to give himself up and become a prisoner again.

Between the Wars

Following the war, illness prevented Strachwitz from remaining in the army. As his health returned, his bold character shone through once more. He wore his uniform, in open defiance of Communist agitators causing trouble in Germany, challenging them to take him on.

Polish forces invaded eastern Germany. The Versailles Treaty prevented the Germans from sending regular troops into the area. Strachwitz was among the men who took up arms to protect their homeland, forming illegal Friekorps units. His group was so successful the Poles put a price on his head and he was given the honor of spearheading the last great German attack of the war at Annaberg.

After the war against Poland, Strachwitz turned his hand to farming. In 1934, while watching armored fighting vehicles carry out a training exercise, his excitement for the military life returned. He rejoined the army, becoming an officer in a panzer regiment.

Poland and France

During the 1939 invasion of Poland, Strachwitz proved how well he had learned the art of armored warfare. His daring and panache led to great successes and a growing reputation. That was when he earned his nickname; the Panzer Graf or Panzer Count.

In the summer of 1940, he took part in the fighting in the Low Countries and France. There, he carried out raids deep into the rear of the Allied forces.

His most famous success of the campaign was a matter of bluff. When he and his driver arrived in a French town alone, they pulled up in front of a military barracks. Marching up to the main gate, Strachwitz demanded the troops inside surrender or be fired upon by his panzer regiment. The garrison surrendered, not knowing there was no such regiment in the area.

On the Volga

A year later, Strachwitz took part in the invasion of Russia. During an early mission, while Soviet infantry surrounded his unit, he leaped from his tank to defend a damaged machine and its crew. While attacking the Russians, he was hit by a bullet. He had it cut out – then went straight back to the fighting.

Despite increasingly fierce Russian resistance, Strachwitz had great success in fighting around the Volga. On one occasion, his camouflaged tanks surrounded a Soviet aerodrome near Stalingrad without being detected. They then opened fire, destroying 158 aircraft as they tried to land.

Strachwitz specialized in raids against the enemy, leading infantry to capture Russian supplies when theirs ran short. As his forces were whittled down, he resorted to swift hit-and-run operations, lightning strikes that avoided further losses.

Kharkov

Strachwitz’s reputation earned him a promotion to colonel and command of a battalion of the new, sturdy Tiger tanks. He had his first chance to use them during the fighting for Kharkov, in which the Germans withdrew and then struck back, seeking to recapture the city.

During the Kharkov offensive, Strachwitz and his men were holding a village forward of the main line when they learned that a Russian armored column was coming their way. Night was falling, and Strachwitz decided to stay hidden, letting the Russians drive past.

The Russians advanced cautiously. When they concluded that the way was clear, they settled down for the night in and around the village. Strachwitz and his men remained silent.

As the sun rose, Strachwitz could see the Soviet command vehicle was less than 50 meters away. He passed orders to his men in whispers, then opened fire. Surprising the Russians, the Germans destroyed the entire enemy column.

Riga

After further successes and another injury, Strachwitz was made major general in charge of the 1st Panzer Division, as well as senior panzer officer in Army Group North. He was permitted to act independently as part of German efforts to break the Soviet encirclement of Riga.

Showing his usual flare for bold maneuvers, he swept around the town of Tuccum before descending upon it. There, he destroyed a Soviet armored formation lined up in the town square. His tanks refueled from a nearby Soviet supply, then moved on. Appearing behind another Soviet formation, they tricked the Russian commander into thinking they were surrounded, and so he surrendered.

By the time he had fought his way into Riga, Strachwitz had detached so many vehicles to guard Soviet prisoners that he had very few left. His formation was so small that German officers in the city mistook him for a lieutenant.

War’s End

Soon after, Strachwitz was seriously injured in a car crash. He recovered enough to lead a tank destroyer brigade in the dying days of the war and fought his way through Czech partisans to surrender to the Americans.

When he was released, he worked for the Syrian government, reorganizing their army and agriculture. A coup overthrew the government, and he fled the country and returned to Germany, where he died in 1968.