As the Second World War drew to a close, the Allies became suspicious of those they’d previously been fighting alongside. This was particularly clear with the British, Americans and Canadians, who held suspicions about the USSR. In an effort to stop the spread of Communism and the Soviet advance to the west, paratroopers with the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion were tasked with aiding in the liberation of the German city of Wismar, before the Red Army could arrive and take it for themselves.

1st Canadian Parachute Battalion

Although they didn’t earn as much recognition as those with the 101st Airborne Division, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion were involved in some of the most famous engagements of the Second World War.

This group of Canadian paratroopers formed in July 1942 and were the first of their kind in the country; there was pushback initially, as the Army simply had little use for paratroopers outside of wartime. They were trained at Fort Benning, Georgia and RAF Ringway. Taking the best of their training at both locations, a program was eventually developed at Canadian Forces Base, Shilo.

A year after their formation, they were sent overseas to participate in Operation Overlord. During this time, they were tasked with destroying bridges near the Dives and participating in the attack on the Merville Battery. In December 1944, they were moved to fight in the Battle of the Bulge, their last major engagement before Operation Varsity.

Operation Varsity

Operation Varsity was the name given to the airborne segment of the larger Operation Plunder, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery‘s plan to move Allied troops across the Rhine and into northern Germany. It involved deploying over 16,000 paratroopers in thousands of aircraft, making it the largest airborne operation ever launched in one location on a single day.

The larger operation took place between March 23-27, 1945 with the airborne forces landing on March 24. There’s some debate over how necessary this additional aerial assault was – some claim Montgomery just wanted to put on a good show – as the US forces had already crossed the Rhine in two different locations. Regardless, they certainly completed their missions effectively.

New orders

The paratroopers landed near the city of Wesel. The 17th US Airborne Division captured Diersfordt and cleared the area of Germans, while the 6th British Airborne Division took Schappenberg and Hamminkeln and captured three nearby bridges.

During Operation Varsity, the Canadians, attached to the British, were tasked with helping clear the drop zone and holding its western side. Tragically, they lost their commanding officer, Lt. Col. Jeff Nicklin, during the initial drop. He was later found riddled with bullet wounds, hanging from his parachute in a tree right over a German entrenchment.

This came as a shock to his men, as he was described as “one who almost seemed indestructible.” Lt. Col. Fraser Eadie took over in his stead, leading the men after Nicklin failed to show up at the rendezvous point.

Canadian paratroopers push on

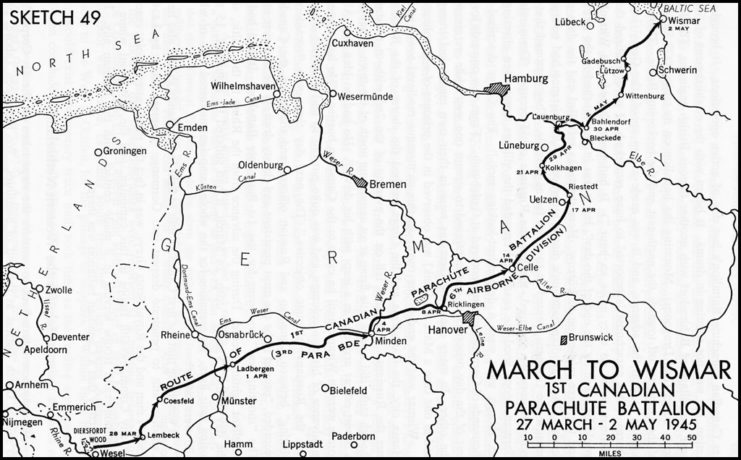

Eadie took control of the fight against the German I Parachute Corps for a day and a half before they finally gained control of the area. After the success of Operations Plunder and Varsity, paratroopers with the 1st Canadian and 6th Airborne joined with the British Second Army to march on the city of Wismar in Northern Germany, to prevent the westward advance of the Soviet Red Army.

This was a large undertaking, as it took them 37 days to cross 459 km of German territory. The Canadians were told to take the lead, with Maj. Stanley Waters spearheading the charge in his tank. His driving was memorable, with Eadie recalling, “Waters was a Calgary boy. His cowboy instincts took over and he drove the tanks on at maximum speed.” Another comrade remarked, “I never realised that a Sherman could do 60 miles an hour.”

Encountering the German enemy along the way

The men met many German soldiers along the way, yet rarely encountered combat. What went in their favor was that the war was coming to an end and the majority of the enemy troops had either given up or wanted the Canadian paratroopers to keep moving to intercept the Soviet advance. Some of the groups they encountered even went so far as to cheer them on.

Occasionally, they were met with gunfire, but it generally didn’t last long.

One account perfectly describes the Canadian experience, “The strangeness of the situation is that we are passing complete units of the German Army, lying by the roadside, some with vehicles, even horse-drawn artillery, but no shots are exchanged, no white flags shown, and we cannot stop to disarm them. This advance is absolutely fantastic to describe. We are bashing our way through what must be divisions of the enemy.”

Liberation of Wismar

The group passed through Bergen-Belsen on April 15, 1945, before reaching Wismar on May 2. There, they encountered their first real resistance, as the Germans had fortified a roadblock at the city entrance – it didn’t hold long. Afterward, the Allies spread out, to ensure there were no pockets of enemy soldiers in hiding.

Overall, they took control of Wismar with ease. Kai-Michael Stybel, director of tourism in Wismar, recounted the liberation, “The Canadians were here and everybody was happy and relieved that there would be no fighting.”

Within a few hours of their arrival, the Red Army appeared – Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky and the 3rd Tank Corps, 70th Army of the 2nd Belorussian Front. Despite their dissatisfaction with the Allies beating them to Wismar, the Red Army was all too happy to socialize with them. The official Canadian written account called them the “most persistent and thirsty drinkers they had ever met.”

The city transfers hands

Although the two sides appeared to be fast friends, their relationship quickly broke down, and the Soviets established their own roadblock alongside the occupying Canadians. Ultimately, Montgomery flew to the city on May 7, 1945 to meet with Rokossovsky, handing the city over to the Soviet Occupation Zone established by the Yalta Conference.

The Canadians were then sent back to the UK, before returning home on June 21.

More from us: Academy Award-Winning Actor David Niven Had to Fight to Serve In WWII

The occupation of Wismar may seem like an insignificant part of the war, especially since the Allies handed the territory over to the Red Army in the end. There are many, however, who believe that the arrival of the Canadian and British paratroopers before the Soviet forces was actually an extremely important maneuver, as it prevented their advance into Denmark, effectively blockading them in Germany.