The HMS Prince of Wales (53) was one of five King George V-class battleships commissioned during the Second World War. Laid down at a time when both the Washington Naval Treaty and the Treaty of London were still in effect, she was smaller and less powerful than her German counterparts. Her design also made her vulnerable to air attacks, as shown in her sinking by Japanese bombers just days following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Construction of the HMS Prince of Wales (53)

The HMS Prince of Wales was ordered in July 1936 as the HMS King Edward VIII. However, her name was swiftly changed after he abdicated the thrown that December. At the time, Britain was under the constraints of both the Washington Naval Treaty and the Treaty of London, which limited the size of her main naval guns to just 14 inches.

The King George V-class battleship was laid down at the Cammell Laird shipyard in January 1937 and launched just over two years later. When the Second World War broke out in September 1939, her construction was accelerated, meaning a number of steps were skipped. This included the testing of her fuel-oil, bilge and ballast systems and the postponement of ventilation and compartment air tests.

Prior to her completion, Prince of Wales was the target of a German air strike. In August 1940, while being fitted at a drydock, a bomb was dropped from overhead. It fell between the battleship and wet basin wall, and exploded just six feet from her port side. Shell plating buckled, rivets sprung loose and severe flooding occurred as a result, with a joint effort between the shipyard and a local fire company needed to remove the water.

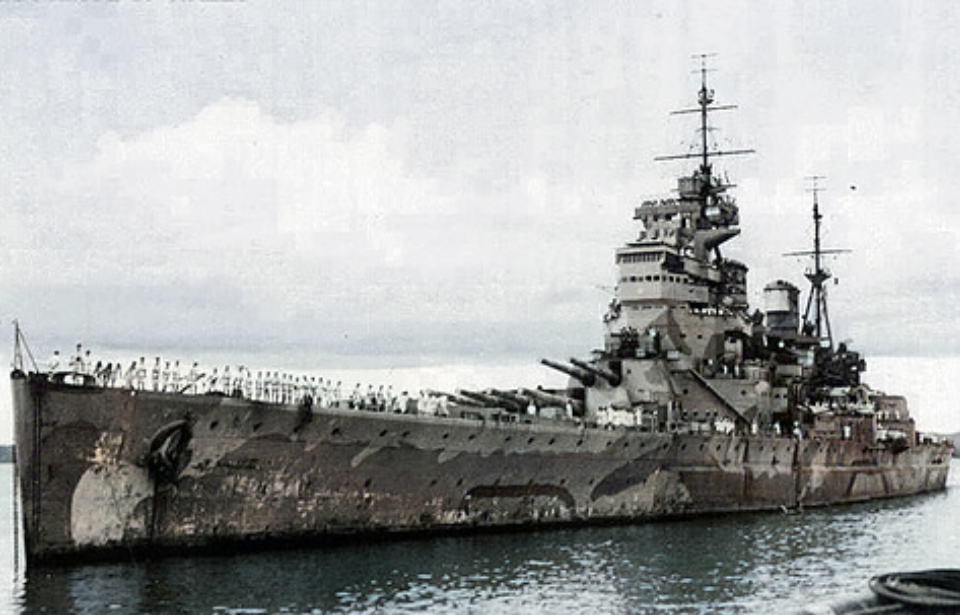

Upon her completion in early 1941, Prince of Wales was ready to sail the seas. She had a displacement of 43,786 long tons when fully loaded, and when traveling at 12 MPH had a nautical range of 18,000 miles. Her armaments included: 32 QF two-pounder Mk VIII “pom-poms,” 10 BL 14-inch Mk VII naval guns, 80 Unrotated Projectile (UP) projectors and 16 QF 5.25-inch naval guns.

On top of that, she housed four Supermarine Walrus seaplanes for reconnaissance, search and rescue, and patrol duties.

Battle of the Denmark Strait

With the Kriegsmarine expanding its efforts in the Atlantic, the British Royal Navy began dispatching vessels to patrol areas through which the Germans were most likely to travel. The heavy cruisers HMS Suffolk (55) and Norfolk (78) were sent to the Denmark Strait, while the HMS Prince of Wales, Hood (51) and six destroyers were positioned south of Iceland. The latter group was awaiting the arrival of the German battleship Bismarck as part of Operation Rheinübung.

On May 23, 1941, Bismarck was reported to be heading southwest along the Denmark Strait, accompanied by the German cruiser Prinz Eugen. Vice Adm. Lancelot Holland told the crews of Prince of Wales and Hood to focus on the former, while Suffolk and Norfolk were instructed to keep eyes on the latter. Unfortunately, the cruisers didn’t receive their orders.

At approximately 5:53AM on May 24, the British ships began firing at the German vessels, albeit with some confusion over which one was Bismarck. Hood aimed at Prinz Eugen, while Prince of Wales set her sights on Bismarck. Both sides were able to secure hits on each other, despite Prince of Wales‘ guns suffering issues throughout the engagement.

Ultimately, Hood sustained enough damage to cause her to explode and sink, killing 1,419 of her crew members. Prince of Wales was able to secure a number of shots on Bismarck, which caused the German battleship to lose 1,000 tons of fuel-oil and suffer flooding to her auxiliary boiler machinery room.

When Hood sank, Prinz Eugen‘s crew turned their sights to Prince of Wales. With two against one, the battleship’s commander, Capt. John Leach, ordered his crew to disengage and create an adequate enough smoke screen to allow their retreat. Bismarck was forced to abandon her mission and return to dock for repairs, and just three days later was sunk by the British in retaliation for the loss of Hood.

Sinking of the HMS Prince of Wales (53)

Following her deployment in the north Atlantic, the HMS Prince of Wales escorted one of the Malta convoys as part of Force H. During the voyage, they were attacked by Italian aircraft, with the battleship successfully downing a number. This was followed by her being named the flagship of Force Z and stationed near Singapore.

On December 6, 1941, the fleet noticed Japanese troop-convoys in the distance, and, two days later, the enemy launched their first attack. While Prince of Wales engaged the aircraft, she wasn’t able to secure any hits. Soon after, the Admiralty requested Royal Air Force (RAF) fighters to arrive on-scene and commence hostilities. However, none came.

Japanese aerial reconnaissance aircraft were spotted and, on December 10, Prince of Wales participated in her final engagement, which ended in her sinking off the coast of Malaya. At 11:00 AM, the eight Japanese-flown Mitsubishi G3Ms launched the first of several aerial assaults, securing a direct hit on the HMS Repulse (1916), which had arrived in the area as part of Force Z.

At 11:30 AM, 17 more G3Ms arrived on the scene, this time split into two formations. Prince of Wales was struck by a torpedo, which caused severe flooding on the port side aft. Listing heavily, her crew could only watch the Royal Navy ships continue to fall victim to Japanese torpedoes.

At 12:23 PM, Repulse was struck by a torpedo dropped by a Mitsubishi G4M, which caused her to sink. The same attack saw Prince of Wales hit by three explosives, resulting in further damage and flooding. The death blow came when a 500-kg bomb struck the battleship. The order to abandon ship came at 1:15 PM, and, five minutes later, Prince of Wales capsized and sank. Three-hundred and twenty-seven crewmen perished.

Remembering the sacrifice of a British battleship

The wreck of the HMS Prince of Wales lies 223 feet down in the South China Sea, near Kuantan, Malaya. In 2001, the site was designated a “Protected Place” under the Protect of Military Remains Act 1986.

More from us: How the USS Yorktown’s (CV-5) Sacrifice Helped Lead the US to Victory at Midway

The following year, the battleship’s bell was manually raised by technical divers and restored, after which it was presented to the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool. It’s since been moved to the National Museum of the Royal Navy at the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard.