As World War II neared its end, the United States formulated a bold initiative called Operation Downfall—a massive, two-part invasion intended to force Japan into unconditional surrender. Military leaders braced for staggering losses, fully aware that both Japanese troops and civilians were prepared to resist to the last.

The plan involved assembling an enormous Allied force to strike Japan’s home islands, backed by an intricate web of supply and support operations. Ultimately, though, the invasion was called off before it could be executed.

Developing Operation Downfall

After the success of D-Day, it was evident that the end of the war in Europe was drawing near—yet the Pacific conflict still posed a formidable challenge.

In early 1945, Allied leaders gathered at the Argonaut Conference to chart the final moves against Japan. It was here that the framework for Operation Downfall, the massive invasion of Japan, first took form.

Military planners expected the European campaign to conclude by July 1, 1945, with the Okinawa invasion wrapping up by mid-August. Operation Downfall was designed as two enormous offensives: the first set for November 1945, followed by a second in the opening months of 1946.

The initial assault would utilize forces already stationed in the Pacific, while the subsequent stage would be reinforced by divisions redeployed from Europe after Germany’s surrender. The scale of the invasion was unprecedented, envisioned as even larger than the historic Normandy landings.

Operation Olympic

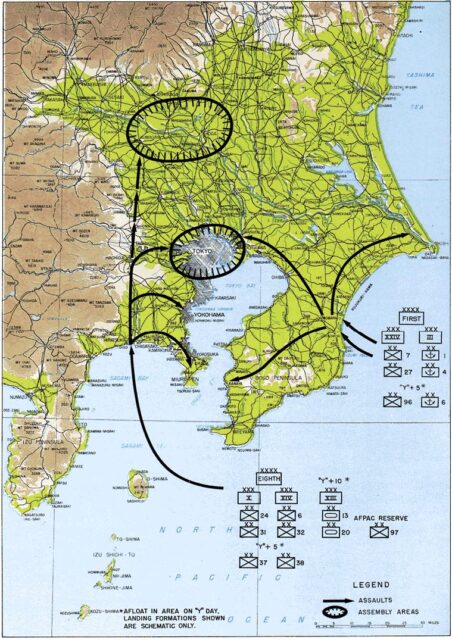

Operation Olympic, the first stage of the broader invasion strategy known as Operation Downfall, was slated to commence on November 1, 1945. Its objective was to seize control of Kyūshū, the southernmost of Japan’s main islands. Launching from Okinawa—which had recently been captured in a bloody and pivotal campaign—American forces would use the island as the primary staging ground for both Olympic and the second phase, Operation Coronet.

The scale of the invasion was unprecedented. Plans called for a vast armada of 400 destroyers and escort ships, 24 battleships, and 42 aircraft carriers that would join the effort. Fourteen divisions and two regimental combat teams would lead the ground assault, supported by a combined Allied fleet that included four Commonwealth battleships and 18 aircraft carriers.

To ensure air superiority and protect landing forces, the Fifth, Seventh, and Thirteenth U.S. Air Forces were tasked with providing cover and striking enemy defenses. Meanwhile, the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific (USASTAF) and Britain’s Tiger Force prepared to conduct long-range bombing runs, with support from the legendary RAF No. 617 Squadron—the “Dambusters.”

Operation Coronet

After the expected completion of Operation Olympic, the United States set its sights on a second and far more forceful assault meant to tighten its grip on Japan by targeting the main island of Honshu. This next phase—code-named “Y-Day”—was slated for March 1, 1946, and was designed to carry the fight straight to the outskirts of Tokyo.

Under the plan, 25 divisions from the First and Eighth U.S. Armies would land at Kujūkuri Beach and Hiratsuka, followed by another 20 divisions driving the advance further inland.

To strengthen the offensive, five divisions from the Commonwealth Corps—composed of British, Canadian, and Australian troops—were incorporated into the operation. Though absent from the original invasion outline, these allied forces were ultimately added to help encircle Tokyo and push onward toward Nagano.

Operation Downfall’s success would have come at a heavy price

While the Americans created a concrete plan for invading Japan, Operation Downfall would have come at a heavy price. As part of the preparation, they did calculations to see what the estimated casualties would be. While the numbers varied, the outcome was always staggeringly high.

One approach taken by Fleet Adm. William Leahy was that the casualties would be similar in number to those experienced on Okinawa – 35 percent. This meant the invasion of Kyūshū alone would have resulted in 268,000 casualties. This number was similarly echoed by Intelligence Chief Maj. Gen. Charles Willoughby.

Some estimates were far higher. One study conducted during deliberations showed that the invasion of Japan would cause up to four million American casualties and around 10 million Japanese deaths. It was these figures that played a role in the decision to drop the atomic bombs.

Operation Ketsugō

As the US planned its invasion, Japan was busy fortifying its defenses. Recognizing the increasing likelihood of an Allied assault, Japanese officials anticipated an attack post-1945 typhoon season. Remarkably, they accurately guessed the invasion locations.

Japan readied itself to counter 90 Allied divisions—20 more than what was actually expected. By this time, Japan understood that victory was out of reach. Instead, the strategy was to inflict such heavy costs on the invaders that the Allies might consider a truce.

Operation Ketsugō, Japan’s resistance strategy, not only involved significant military forces but also mobilized civilians. An extensive training program was put in place for new troops, including frogmen, and 28 million men and women were prepared for the Volunteer Fighting Corps. Additionally, Japan intended to use kamikaze pilots to stop the Allied naval forces from reaching the shores.

Downfall of Operation Downfall

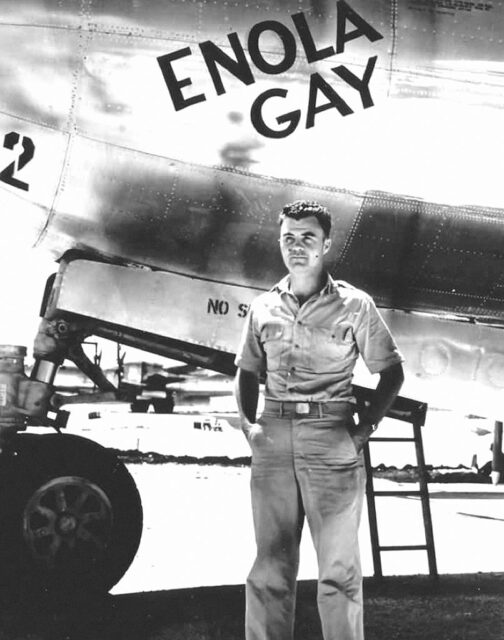

Ultimately, Japan’s preparations were for nothing, as its troops couldn’t withstand the attacks that brought World War II to a close. Before Operation Downfall could be put into action, the Americans dropped the atomic bomb Little Boy on Hiroshima, followed shortly after by Fat Man over Nagasaki. The Japanese surrender and the Soviet advance into Manchuria that followed solidified for the allies that Downfall was no longer needed.

Prior to this, the US really was actually preparing for the invasion. The country even went so far as to create almost 500,000 Purple Hearts in advance of the waves of injured Americans that would come out of Operation Downfall. Since they were never needed, the US military opted to hand out these medals in future wars; so many were made, in fact, that they were given out during the Korean War, in Vietnam, and during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

As of 2020, it was believed there could be as many as 60,000 of these Purple Hearts yet to be given out.