WWII was fought by civilian resistance in occupied countries as well as by armed forces. On many occasions, those groups worked together.

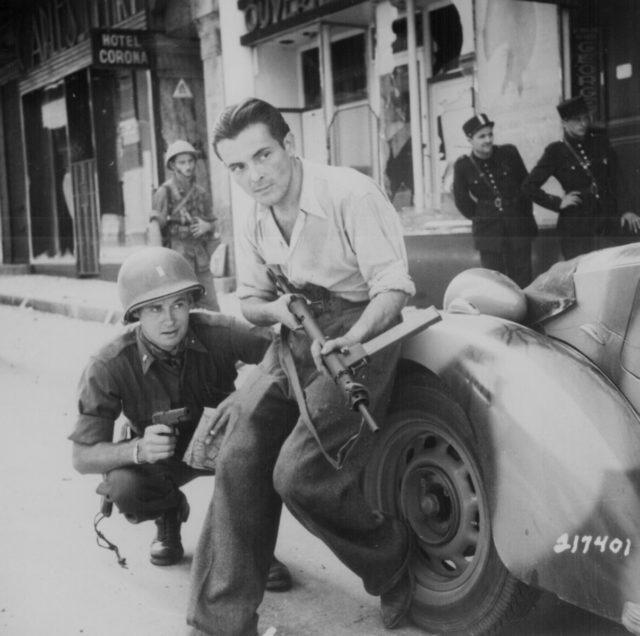

France

The work of the French resistance is rightly famous. Much of it was undertaken on their own initiative, but they also worked in coordination with the Allies. For instance, Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, head of the Noah’s Ark network, saw her main function as gathering intelligence for the British.

It often involved taking huge risks. A group of French telephone engineers tapped the lines of German HQs from April to December 1942, providing transcripts of messages between Paris and Berlin. They were eventually captured and shot.

One of the best sources of the German defenses in Normandy came from the resistance. René Duchez, a painter and resistance leader, was seeking work at the offices of builders working on those defenses. Left alone with a map of the proposed works, he stole it without being caught, providing vital information on German plans.

Agents such as Joseph Antelme and Violette Szabo were dropped into France to coordinate with the resistance and help them build their networks. Both of them died at the hands of the Nazis. Thanks to their sacrifice and the hard work of hundreds of others, the Resistance played a vital role in the invasion of Normandy. They crippled German transport routes, rose against the invaders, and prepared supplies ready for the Allies’ arrival.

Poland

The Polish resistance covered the largest territory and the most difficult struggles of the war.

From the outset, the Poles were resisting invasion not just by the Germans but also by Soviet Russia. A vast network of resistance fighters and information gatherers developed. A country repeatedly invaded by its neighbors, the Poles had a long history of such defiance. They attacked occupying forces and collaborators, released captives, disrupted supply lines, and rescued Jews from the Holocaust.

Some of their most significant collaboration with the Allies was intelligence gathering. Escaped Polish cryptographers provided the groundwork for the decryption of the German Enigma code. Polish information told the British that Germany was about to invade Russia, allowing the British to warn the Russians, who promptly ignored them.

Critically, Germany used Polish forced labor in much of its weapons research, including the development of the V2 rocket at Peenemünde. Poles provided the Allies with information about this deadly new technology. After the Germans had fired test rockets, a Polish resistance leader gathered wreckage from one, carried it miles across the country, and delivered it to Britain via a secret airfield. It allowed the Allies to see what was coming first-hand and to prepare.

Yugoslavia

From the German invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, two resistance movements emerged. One was the royalist Chetniks, mostly ethnically Serbian and led by Dragoljub Mihailović. The other was a diverse Communist network led by Josip Broz, known as Tito.

At first, the Allies backed Mihailović. He had the favor of the Yugoslavian government in exile and promised a bulwark against Communism once the war was over. For two years, supplies were directed toward his forces.

By 1943, it was becoming apparent that while Tito was active against the Nazis, Mihailović was waiting for an Allied invasion. Troops aligned to Mihailović were collaborating with the Nazis in their fight against the Communist guerrillas.

The Allies shifted their support to Tito, including services from an air base in Italy. He continued to lead one of the most effective resistance campaigns on the continent.

Italy

In September 1943, Italy switched from supporting the Germans to joining the Allies. Much of Italy was occupied by German troops and by the remnants of Mussolini’s Fascist regime. There, a partisan network played a very active part in the final years of the war.

The Italians disrupted German communications and harassed their troops. As the Germans increased their brutal measures, the partisans’ resolve strengthened.

From mid-1944 the Allies realized how much they could gain by working with the partisans. The SOE and OSS sent liaison officers to work with them, creating a more coordinated fighting network.

Despite Allied attempts to rein them in near the end, it was resistance fighters who liberated Genoa and made life miserable for the Germans on the road to Venice. After Mussolini’s rescue by German commandoes, they recaptured and executed the former dictator.

Belgium

In Belgium, railway workers played an important part in resisting the Nazis by keeping the Allies informed.

Observing the movement of supply and transport trains, they fed the information to the Allied intelligence services. Some of it was obvious, as when tanks or field guns were seen in transit. At other times, such subtle pieces of information as an empty freight car might provide clues to German dispositions.

So much information was gathered on rail networks across the continent that a special section was set up by the Allies to analyze it. At first, it was used to ascertain the German order of battle. As information flowed in, the Allies ascertained where the most important transit hubs were. By bombing those connection points, they severely disrupted German supplies and communication.

Norway

Intelligence from resistance organizations could help at sea as well as on land. The Norwegian resistance, headed by Jens Christian Hauge, were active throughout the war, striking at German activities in their country. In 1941 they played a part in one of the most significant naval operations of the war in Europe – the tracking and sinking of the Bismarck.

News that the Bismarck had departed from a safe harbor in May 1941 came from the Norwegians. People in neutral Sweden saw the ship sale on the 20th and sympathizers passed that information to the Norwegians, who then gave it to the British. The Norwegian Resistance then spotted the Bismarck sailing along their country’s west coast. It enabled the British to begin their pursuit of the Bismarck, which ended with the sinking of one of the greatest battleships of the war.

Sources:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945.

Gordon Brown (2008), Wartime Courage.

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle.