Zone Rouge – or the “Red Zone” – is a chain of former battlefields across northeastern France that the government has cordoned off due to the many dangerous ordnance that remains from the First World War. The area originally spanned over 460 square miles, from Nancy through to Lille, and incorporates such battlefields as the Somme, Verdun and Vimy Ridge.

While the size of the region has lessened over the 100-plus years since the end of the conflict, the area is still characterized by the scars and remnants of the Great War.

Scars of World War I

Over the course of World War I, an unprecedented amount of munitions were used by the Triple Entente and Triple Alliance to try and gain a victory over the other side. The destruction these weapons caused to the French landscape saw entire villages and cities transformed into rubble and craters. People were driven from their homes, and whole regions were made uninhabitable.

The destruction of the French landscape was one thing, the dangerous remnants of the fighting were another. Across many of the former battlefields are unexploded ordnance, made up of artillery shells, gas shells, grenades and small arms ammunition. Their existence has seen lead, mercury, chlorine, arsenic and acids, as well as human and animal remains, create soil pollution.

These remnants and their effects have seen the complete destruction of life in this region. For instance, 99 percent of all plants die in Zone Rouge, due to the level of arsenic, which constitutes up to 175,907 mg per kilogram of soil. When the area was designated following the conflict, the vast region was viewed as “completely devastated. Damage to properties: 100%. Damage to agriculture: 100%. Impossible to clean. Human life impossible.”

While this was well over 100 years ago, it’s not all that much different today.

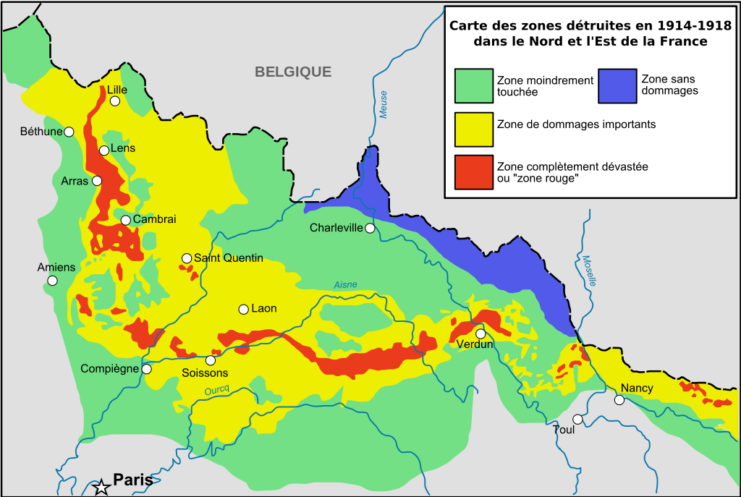

A region comprised of four zones

Zone Rouge is ultimately one of four different ones on and around the former battlefields of the Western Front. Ranging from the most to least dangerous, these areas serve as an eerie reminder of the past.

As aforementioned, the majority of the towns and cities located within these zones – in particular, Zone Rouge – have long since been abandoned in what National Geographic describes as a “minor forced relocation.” When the French government weighed the time and cost of rehabilitating the natural landscape, as well as the inherent dangers, it was decided that total abandonment was the best solution.

“Those villages were considered a casualty of the war,” Joseph Hupy, a geography professor at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, told the publication. They’ve since been given a special name, “village detruits” – or “destroyed villages.”

Since no one can live in these zones, the areas still possess the remnants of war; large shell craters, trench networks and military equipment stick out from the ground. Nature was quick to reclaim the region, with historian Christina Holstein telling National Geographic, “They found the vegetation – trees, grasses, bushes, and briar – all came back very quickly.”

This wasn’t the only life to return, as animals did so, too. While unexploded ordnance still poses a threat to these creatures, the removal of humans has given rise to a unique wilderness in northwest France.

Return to normal?

Zone Rouge will likely never be returned to the state it was before the First World War. That being said, France isn’t planning on keeping the area isolated forever. The government established the Department du Deminage (Department of Mine Clearance) to clear unexploded munitions.

Since its inception, it’s destroyed hundreds of thousands of pieces, allowing the land to be returned to the public. The majority of the cleared region and beyond has been turned into farmland, which is helping to bolster the country’s agricultural sector. That doesn’t mean, however, that farmers and the general public haven’t come across ordnance that’s been missed.

According to Joseph Hupy, those who come across regular shells need not worry, as those rarely kill. “The people who die in the munitions removal, they don’t really die from the explosive ones,” he told National Geographic. “They die from gas shells.”

It’s likely Zone Rouge will never be fully cleared. It’s been projected that it will take at least 300 years of work to completely clear the battlefields of their dangerous remnants. Even then, the likelihood there will still be some shells lurking beneath people’s feet is high.

Iron Harvest

The town and battlefield most think of when discussing Zone Rouge is without a doubt Verdun. It was the site a 300-day battle between the French and Germans, which resulted in over 300,000 soldiers losing their lives. Millions of pieces of ammunition and munitions were used, permanently altering the landscape. A large portion were duds that became lodged in the ground.

Given this, an event known as the “Iron Harvest” has happened annually. Occurring throughout the spring planting and autumn plowing seasons, it sees the collection of unexploded ordnance, shrapnel, trench supports, barbed wire and bullets in both France and Belgium’s rural areas.

There are signs posted at the sides of roads, in the shape of a shell, that indicate where farmers can place unearthed ordnance and wartime remnants. The Department du Deminage will then come by and pick them up.

Development in Zone Rouge

Despite the government closing off the area and the existence of unexploded ordnance, human activity continues to occur in and around Zone Rouge. Hunters, for instance, will hunt deer and wild boar in the area. It’s also become part of the timber industry. As Joseph Hupy stated, “Everyone needs their lumber products, and for the French, this is a great area to practice forestry.”

The landscape of Zone Rouge will likely never return to what it once was. The First World War, bringing destruction to the region, ensured it would never be the same. However, it’s now seeing some new developments. As described by Christina Holstein, “It is a bit like Sleeping Beauty. Things have just gotten frozen in time.”

More from us: The Little-Known Grand Stand of the ‘First Soldier of France’

While Zone Rouge is characterized by the destruction brought about by war, there are possibilities for recovery.