If there’s one thing World War I is known for, it’s the use of trenches as a means of protection and strategy. They could be seen for hundreds of miles along the Western Front, employed by soldiers positioned near the English Channel, all the way to the Swiss Alps. Various types of trenches were employed during WWI, as a way to maximize their value. That being said, they still had their pitfalls.

How trenches changed warfare over the course of WWI

During WWI, trenches provided shelter for soldiers who engaged in the harsh fighting along the Western Front. They also made it difficult for the opposing forces to advance and attack the frontline. Dug under the cover of darkness, they ran eight feet deep and between four-six feet wide. Wood and/or tree posts were used to reinforce the walls and prevent collapse.

Trenches weren’t frivolously built without careful planning; there was a strategic pattern to them. They were constructed in a zig-zag formation, which allowed for the maximum amount of damage to be inflicted against the enemy, while lessening the number of casualties. Straight lines and uniform walls would have allowed for straight shots, so random turns and angled walls, known as traverses, provided quick shelter against artillery.

Both sides employed the use of trenches during WWI, and, in doing so, transformed warfare. As the conflict progressed, so, too, did the architectural integrity of these trench systems, with the Germans developing elaborate defense positions featuring cement pillboxes and dugouts that could withstand Allied bombardment.

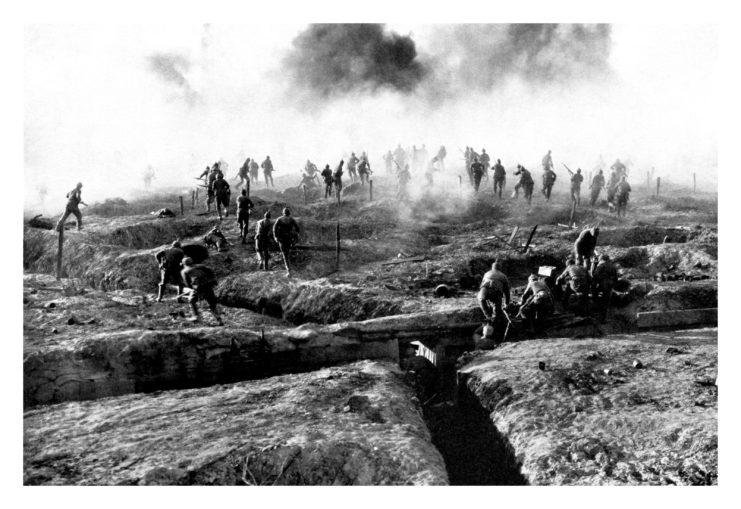

The expanse between each side was dubbed “No Man’s Land,” and it became the area each attempted to gain control of. As such, it was quite dangerous to cross, making the common tactic of launching infantry assaults ahead of artillery attacks particularly deadly. By the end of 1914, for example, the number of dead and injured had exceeded four million.

When the first tanks hit the Western Front toward the end of WWI, it became apparent that trench warfare had met its end, as the tracked vehicles weren’t only able to cross over the muddy expanse of No Man’s Land, they could also drive over trench openings and were invulnerable to most enemy fire.

There were three common methods to digging trenches

There were three main methods of trench-building employed during WWI. The first was known as sapping, wherein soldiers dug shallow trenches that extended into No Man’s Land from larger ones. This was the safest way to extend the systems, as shallow areas could be built by one or two soldiers and reinforced as regular trenches were extended from them. In some cases, sapping was used for rescue and retreat purposes.

Tunneling was another common form of trench-building, and it followed a similar system to sapping. Tunnels were constructed underground to provide cover from enemy fire, making them safer than regular trenches, which didn’t have overhead coverings. They were used to protect injured soldiers, and were also employed during night raids on enemy positions. Additionally, the roofs could be collapsed to create regular trenches.

Sandbagging was the third form of trench-building seen during WWI, serving as a deception tactic. While sandbags were effective at providing cover from rifle fire, they did little to protect against artillery. As such, they were stacked and covered in dirt and grass, to camouflage them and give the appearance of being underground. On occasion, they’d also be decorated to look like soldiers, so the enemy would accidentally reveal their location during an attack.

British trenches during WWI

British trenches were divided into four different types. The frontline trench, also known as the outpost line, was the closest to the enemy, located between 50 yards and one mile away. Barbed wire lined the top, providing protection for those manning them, such as sparsely-positioned machine gunners. Soldiers would spend one week in the frontline trench before retreating to the rear, alternating weekly.

The support trench was located several hundred yards away and provided support to the frontline, housing first aid stations and food preparation spots. It also served as a second line of defense, in case of the frontline trench becoming overrun. The reserve trench was even further back and served as an emergency position, should both the frontline and support trenches be taken over by the enemy.

Communication trenches connected the aforementioned types, allowing soldiers to move from the front to the rear and vice versa, sending messages and supplies wherever needed. They also served as paths across which injured soldiers were carried, removing them from immediate danger and providing a better chance of transporting them to nearby field hospitals.

Within these trenches, artillery lines could be found, as well as machine gun nests manned by two or three soldiers. Underground bunkers were also dug along them, as a means to store food, weapons and artillery. They also served as command centers, with telephone lines allowing for the transmission of information and instructions.

Extending closer toward the enemy than the frontline trench was the listening post, where tunneling was employed to create a position that stretched 30 meters under No Man’s Land. From there, soldiers equipped with stethoscopes listened to ground vibrations to determine any movement above.

Death came in many forms in the trenches

Despite the immediate protection trenches offered, they were also extremely dangerous – and for multiple reasons. If a trench became overrun by the enemy, soldiers could become trapped and fall victim to direct fire, as they weren’t the easiest spaces to escape from. Although the zig-zag design did reduce the possibility of such an event occurring, those who weren’t quick enough were easily caught by enemy fire.

One of the most deadly issues to stem from trenches during WWI was trench foot. Rain and shallow water tables caused flooding, and if soldiers stood in said water for too long, their feet became waterlogged, swollen and blistered. The disease could become so severe that those afflicted with it would need their foot/feet amputated to prevent the spread of infection – or even death.

More from us: Anna Coleman Ladd: The Sculptor Who Changed the Lives of WWI Veterans

To prevent trench foot and flooding, a narrow drainage channel was built into the trenches that lined the Western Front. They were covered by wooden boards known as “duck boards,” which raised the standing area and kept soldiers’ feet somewhat dry. As well, sandbags could be thrown into the bottom of trenches as a method of soaking up some of the water.