Throughout World War I, women took on a whole host of new roles to contribute to the war effort, including nursing, firefighting and engineering. Unlike many others, Anna Coleman Ladd didn’t work in a traditional field. Rather, she used her penchant for sculpting to create custom masks for soldiers who’d suffered facial deformities as a result of injuries sustained in combat.

Anna Coleman Ladd’s work as a sculptor

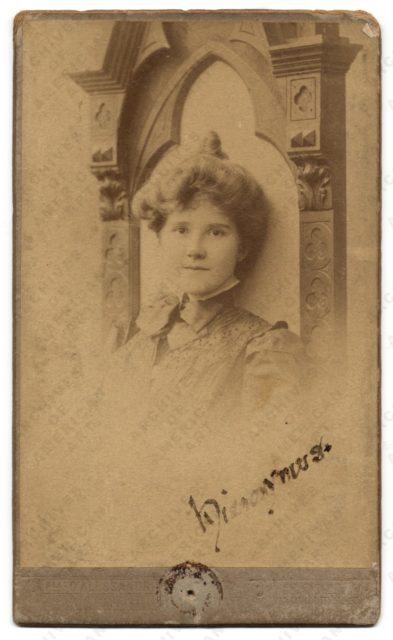

Anna Coleman Ladd, née Watts, was born in Pennsylvania on July 15, 1878. She was educated overseas, studying sculpting in Rome and Paris, before moving back Stateside to study at the Boston Museum School. She eventually married Dr. Maynard Ladd in England, after which the pair moved to Boston. One of her pieces, Triton Babies, is featured in a fountain at the Boston Public Garden.

In 1914, Coleman Ladd joined the Guild of Boston Artists as a founding member, with whom she exhibited much of her work. Her career continued until 1936, when she retired to California with her husband, dying only three years later.

While she gained fame for her museum-quality work, it was her efforts during and after the First World War that she’s best known for, not only creating masks for soldiers with facial deformities, but refining and improving the art behind the skill.

Combat and the resulting facial deformities

The advancements in military technology during WWI were useful, as they allowed for more aggressive and effective combat. On the other hand, these weapons led to horrific injuries that were difficult to recover from. As explained by a doctor who’d served on the front, “Every fracture in this war is a huge open wound with a not merely broken but shattered bone at the bottom of it.”

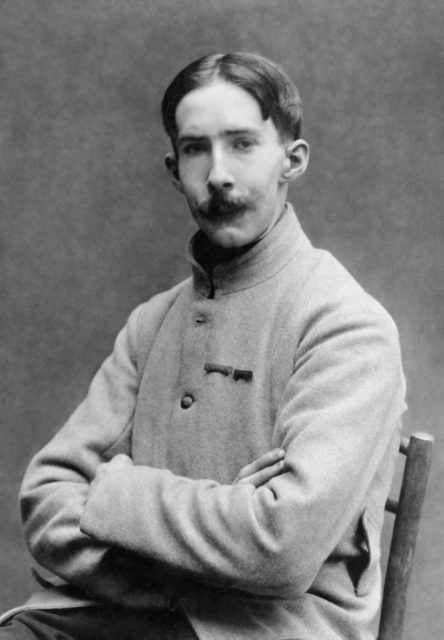

This assessment can also be applied to the human face. Fred Houdlett Albee, a surgeon during the conflict, wrote, “It is a fairly common experience for the maladjusted person to feel like a stranger to his world. It must be unmitigated hell to feel like a stranger to yourself.” For context, severe facial disfigurement was one of few injuries for which veterans earned a full pension in the United Kingdom, as the men were “condemned to isolation” because of their condition.

Of the injuries inflicted during combat, facial disfigurement was generally considered to be the most traumatic, due to how alienating it could be for the victim. Although medical care was advanced enough to make such wounds survivable, many were unable to drink, eat or speak after undergoing reconstructive surgery.

Mastering the technique

In 1917, Anna Coleman Ladd discovered the work of Londoner Francis Wood, who was making masks for wounded soldiers. After approaching him, the two began working to improving his technique. Wanting to continue this work, she obtained permission to go overseas and work with the American Red Cross, eventually opening the Studio for Portrait Masks.

It was important to Coleman Ladd that the space was welcoming for soldiers, so she designed it to include flowers, posters, and both the French and American flags.

The sculptor worked alongside four assistants to make life-like masks for injured servicemen. She was exceptional at her craft, taking plaster casts of the men’s faces, so she could accurately replicate the facial features from their “good” side. The mask would then be made from copper and painted to match the color of the soldier’s skin – natural hair was even used to create eyelashes, mustaches and eyebrows. From start to finish, it took a month to complete the finished product.

The masks were usually held to the face by glasses or string. It reached a point where Coleman Ladd was so good at creating them that she was able to do so by simply looking at photos of the servicemen prior to them suffering their injuries. This set her studio apart from Wood, and she was generally credited with producing finer work.

Anna Coleman Ladd changed many lives

It’s recorded that roughly 3,000 French soldiers received corrective masks, of which Anna Coleman Ladd made 185. For her work, she was awarded the Croix de Chevalier de l’Ordre de la Légion d’Honneur and the Serbian Order of Saint Sava. Although she made many masks, none survived into the present day – they either fell apart due to use or their wearers were buried with them.

The masks Coleman Ladd created undoubtedly changed many soldiers’ lives. Aside from her awards, the sculptor received many letters from clients, who praised her work and thanked her for what she did for them.

More from us: What Happened to the Jewish Soldiers Who Served with the German Army in World War I?

One serviceman expressed his thankfulness that his wife no longer found him repulsive, while another wrote, “My gratitude to you will last forever and I will never forget for I wear and will always wear the wonderful fittings which you came up with and it is thanks to you that I can survive being under fire. It’s thanks to you that I am not buried deep in an old veterans’ hospital.”