Legendary exotic dancer Mata Hari was much more than meets the eye. With her captivating beauty, alluring performances and alleged involvement in espionage during the First World War, she was a truly complex figure. However, her life and death weren’t quite so black and white. Over 100 years after her execution, questions are still being raised as to whether she was truly a devious femme fatale or a convenient scapegoat.

Born Margaretha Geertruida Zelle

Mata Hari was born Margaretha Geertruida Zelle on August 7, 1876, in the Netherlands. She led a relatively affluent childhood, as her father ran his own shop and made additional money through the oil industry. This meant Zelle was able to attend the best schools – that is, until the age of 13, when her father went bankrupt. This put significant strain on her parents’ marriage and they eventually split. Shortly after, her mother died.

Although her father eventually remarried, the family was never the same, and Zelle was sent to live with her godfather. She tried to study to become a kindergarten teacher, but this was short-lived. The headmaster continuously flirted with her, prompting her godfather to pull her out of the institution.

Zelle soon left the home and took refuge with an uncle in the Hague.

Becoming Margaretha MacLeod

Margaretha Geertruida Zelle married Dutch Colonial Army Capt. Rudolf MacLeod after seeing an advertisement he’d place in a local newspaper – he was hoping to find a wife. The two married in July 1895 in what was likely a strategic union on Zelle’s part, as MacLeod was part of the Dutch upper class and had a sizeable fortune.

Two years later, the pair moved to the the south Pacific – in particular, Malang, on the west side of Java. For four years, they lived at several military bases, and they had two children, Norman-John and Louise Jeanne.

However, the pair’s relationship was truly horrid, with the much older MacLeod abusing his wife. He was also a terrible drunk. At one point, Margaretha wrote he “came close to murdering me with the breadknife. I owe my life to a chair that fell over and which gave me time to find the door and get help.”

In 1899, things got worse when their children fell very ill and Norman-John died. The official line was that an enemy of the family poisoned them, but other sources say it was caused by a treatment for syphilis, an infection they likely caught from their parents.

The MacLeods divorced in 1902. Even though custody of Louise Jeanne was given to her mother, her father decided to not give her back after a visit. He also never paid child support, despite being ordered to do so. Louise Jeanne died of unknown causes at the age of 21.

Career as Mata Hari

In 1903, Margaretha MacLeod moved to Paris. She joined a circus as a horse rider under the name “Lady MacLeod” and posed as an artist’s model to supplement her income.

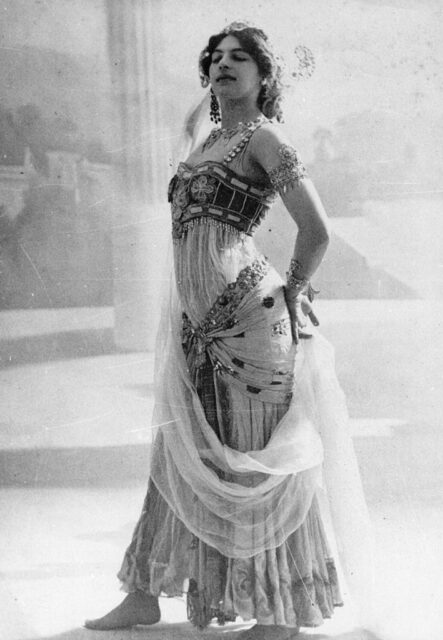

In 1904, she became an exotic dancer, under the stage name “Mata Hari,” which translates to “eye of the day” in Malay. Having taken dance classes while living in the Dutch East Indies, she was skilled at the craft. Her theatrical debut occurred on March 13, 1905 – and she was an immediate hit.

For her act, Hari – described as “promiscuous, flirtatious, and openly flaunting her body” – created an elaborate backstory about being born in a temple and taught “sacred” dances by a priestess. She’d typically strip from the waist down, posing this way for many photos, and became known for wearing a bejewelled breastplate.

Hari eventually became the mistress of French millionaire Émile Étienne Guimet, and was known to mingle with Paris’ upper class. This was aided by her fictitious backstory, which many believed to be true.

Outbreak of World War I

As the years went on, similar acts arose in Paris and Mata Hari became less popular.

By the time she performed her final show in 1915, she’d formed several relationships with extremely high-ranking officials, many of whom were with the German military. She often traveled internationally with these men, which, prior to the outbreak of World War I, was largely dismissed. However, when the conflict began, her actions were viewed as far more suspicious.

Hari returned to the Netherlands in 1914 and, as a neutral Dutch citizen, could freely move throughout Europe. To avoid the fighting occurring on the Western Front, she typically traveled between there and France via Britain and Spain.

Exotic dancer-turned-spy

Mata Hari’s alleged espionage career began after she fell for Russian pilot Capt. Vadim Maslov, who was serving alongside 50,000 other countrymen on the Western Front. During a dogfight with German aircraft, he was shot down and badly injured, losing the sight in his left eye. Concerned for her beau, Hari tried visit him while he recuperated in a hospital near the frontlines, something neutral civilians weren’t typically able to do.

This is where her story gets complicated, as there are many contradictory accounts of her actions. Supposedly, Hari’s efforts to see Maslov caught the attention of French Intelligence officer Capt. Georges Ladoux, who brought her in for questioning. She assured him that her loyalties lay with France, something he’d hoped she would prove by agreeing to spy on their behalf. Hari didn’t agree until she saw the horrible condition her lover was in, and she only did so in exchange for financial compensation.

Some accounts say she’d earlier committed to passing on information to Germany after her next trip to France – details she swore were outdated. Over the next months, Hari made several trips, which increased speculation over whether she was sharing French secrets with German military officials.

These suspicions were seemingly proven when, in January 1917, the French intercepted a German message about a spy known only as “H-21.” The agent’s information was identical to Hari’s, and French Intelligence later claimed to have confirmed H-21’s identity as being the former exotic dancer.

Mata Hari’s trial and execution

In order to test her, the Second Bureau of the French War Ministry allowed Mata Hari to learn the names of six Belgian agents – one double agent and five who were suspected of working alongside Germany and submitting fake documents. After traveling to Madrid, the Germans just so happened to execute the alleged double agent, serving as proof to the French that she was indeed collaborating with the enemy.

Hari was arrested on February 13, 1917. At her trial a week and a half later, she was accused of passing on information that had caused the deaths of 50,000 French soldiers. Despite the accusations leveled against her, neither French nor British Intelligence could provide concrete evidence that Hari was spying for Germany. Instead, they tried to prove their case by slandering her character, using her fictitious backstory as a dancer to make the claim she was a liar.

Although Hari always maintained her innocence, she was found guilty. The sentence? Execution. The Dutch government did nothing to intervene on her behalf.

On October 15, 1917, Hari was shot by a firing squad of 12 French soldiers. Her execution was witnessed by British reporter Henry Wales, who asserted she went without being bound and refused a blindfold – she even blew a kiss at the firing squad. Wales added that, even in the face of death, “she did not move a muscle.”

Ironically, Georges Ladoux was arrested only four days after her execution for the same crime. He was ultimately cleared of all charges.

Questioning Mata Hari’s crimes

The matter of whether Mata Hari was a spy is still heavily debated. The most popular theory is that she was simply used as a very convenient scapegoat by the French, who’d suffered significant losses in the months leading up to her arrest. The thought appears to be that it would be better to have someone to blame these failures on, and it seems likely that Hari was an easy person to target, having had well-documented relationships with German officials prior to WWI.

As early as 1930, Hari was declared innocent by the German government, although they had less to answer for than the French officials who’d ordered her execution. Documents from both MI5 and the French Army have since been released, which further support the theory she was innocent, at least of any grand espionage.

One of the dancer’s biggest advocates is the Mata Hari Foundation, which believes many of the documents were falsified to obtain a desired trial outcome; the organization has repeatedly asked the French to exonerate her of being a spy.

More from us: USS Recruit (1917): The Wooden Dreadnought In Manhattan’s Union Square

The Mata Hari Foundation’s stance is that “there are sufficient doubts concerning the dossier of information that was used to convict her to warrant re-opening the case. Maybe she wasn’t entirely innocent, but it seems clear she wasn’t the master-spy whose information sent thousands of soldiers to their deaths, as has been claimed.”