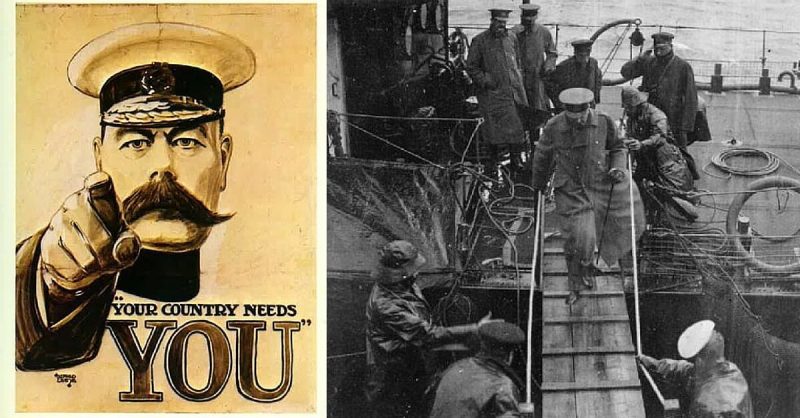

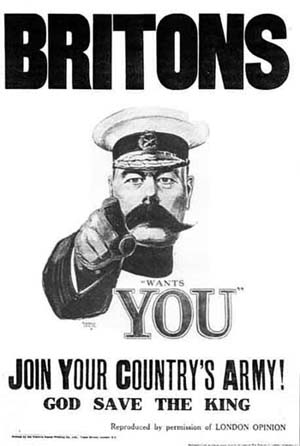

One of the most iconic images from the great war of 1914-18 is the recruitment poster featuring the commanding moustachioed face of the Lord Horatio Herbert Kitchener. His finger points out at the viewer, accompanied by the words “Britons! Join your country’s army!”

Kitchener was a career soldier, born in County Kerry in Ireland in 1850. The son of a Lieutenant Colonel, he began his military career at a young age, completing his education at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, England.

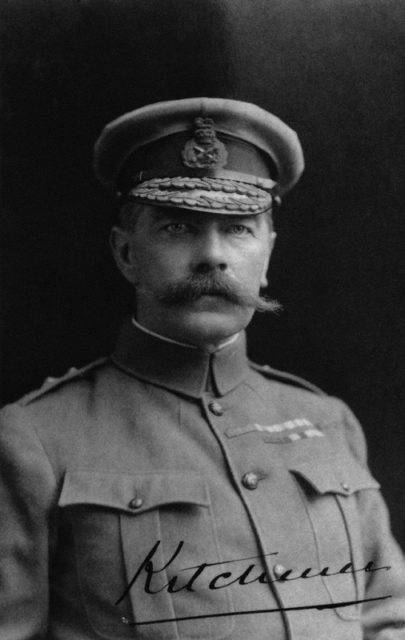

By the time of the outbreak of war in 1914 Kitchener had a long and distinguished military career behind him. He had seen action throughout the British Empire and was well known and well liked by the British public. Physically, he was an imposing man.

He stood over six feet tall, and his height, his huge moustache, his steely eye and his impressive achievements as a soldier combined to make him one of the most celebrated military commanders of his day. His face was so well known to the public that the original Kitchener recruitment poster did not even need to feature his name.

Kitchener had passed his 64th birthday in June 1914. He had attained the rank of field marshal, the highest rank possible in the British Army. Shortly after the outbreak of war in July of the same year, he was appointed Secretary of State for War by the British Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith.

Popular opinion was that the war would be over swiftly, but Kitchener thought differently. He predicted not only that the war would last for years, but also that numbers of casualties would be huge before the conflict was over. The famous poster was part of a huge recruitment campaign he initiated, and within eighteen months the British Army had been swollen by volunteers numbering into the millions.

As the war progressed, Lord Kitchener’s popularity with the public remained high, but behind the scenes, his dominant personality made him difficult to work with. His colleagues in the military and political high command were unhappy with him. Disagreements over military priorities and command structures combined with difficulties with supplies for the army, and it seemed to some that Kitchener’s grasp on his command was slipping. The strain of command was telling on him physically and mentally and his strategic vision was becoming further and further removed from that of the other British commanders.

It was against this backdrop of uncertainty in June 1916 that Kitchener was dispatched on a diplomatic mission to Russia. The Russian efforts on the Eastern Front were wavering, with the Russian Army’s retreat from Warsaw in August 1915, and the disastrous Russian offensive at the Battle of Lake Naroch.

Negotiations were to be held in Russia, and Lord Kitchener set sail for the Russian port of Arkhangelsk (Archangel) at the start of June. His journey began in the immediate aftermath of the great Battle of Jutland, the biggest naval engagement of the First World War, and he was to set out from the base of the British Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow. This is a great sheltered anchorage in the windswept archipelago of the Orkney Islands, north of mainland Scotland.

The Orkney Islands (or simply: Orkney) had a great strategic importance for the British during the First World War. To this day gun turrets and fortifications can be explored along the coast of the main landmass, looking out over the great expanse of Scapa Flow. Fresh from the Battle of Jutland, in which she had played only a small part, the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire was here to receive Lord Kitchener on June the fifth, 1916.

Her escort was small, two destroyers; Unity and Victor. Her crew numbered 655 men. She carried seven passengers including Kitchener. The seas were heavy, and the wind had built to force nine gale, with wind speeds reaching ninety miles per hour. The rain was cold and relentless.

It had been decided that HMS Hampshire would travel up the West side of the biggest island in the Orkney archipelago. This would, thought her captain, shield her from the worst of the gale, and would allow the less powerful escort ships to keep pace. They travelled West through the Pentland Firth, then North up the coast, passing the huge cliffs at Yesnaby in the driving rain.

Then the wind changed. It increased in intensity and shifted to the North so that the little convoy was pushing straight into the teeth of the gale. The destroyers began to fall behind, and the captain of the Hampshire decided that they were not needed. After all, what German U-boat could brave these conditions? He gave the order for the escort to return to base.

He was right. There was no enemy ship in the region. Save for HMS Hampshire the surface of the sea was empty, but this did not mean that there was no threat. In the preparation for the Battle of Jutland, which had occurred in the North Sea to the East of Orkney, the German minelayer U-75 had laid a several sea mines on the route that HMS Hampshire would take.

They were approximately a mile and a half from the main landmass of Orkney and were passing the small, uninhabited, wedge-shaped island known as the Brough of Birsay. The time was 7:40 pm; visibility was poor. Below decks Kitchener and his staff were settling for their long voyage.

A mine struck HMS Hampshire forward of the bridge. On land, a boy and his father, working in spite of the rain, saw the flash, followed a moment later by the faraway thud of the explosion. On board, the crew scrambled to lower lifeboats, but their efforts were futile. The huge north sea waves smashed the lifeboats to kindling against the cruiser’s side.

On the land, the fishermen from a local village tried to put to sea in their small craft to attempt a rescue, but the huge sea and gathering dark made it impossible, and they watched the burning ship from the shoreline, helpless.

It did not take long for HMS Hampshire to succumb to her wound. She sank, bow first, less than twenty minutes after the explosion. Of the 655 people on board, only twelve were saved, drifting to land clinging to small floats. Lord Horatio Kitchener was never seen again.

Today, the wreck lies upside down at a depth of around 40 fathoms and is designated as a war grave. We must assume that the bones of Lord Kitchener lie there also.

– by Barney Higgins