Many feats of valor are celebrated with medals and honors, yet some heroes go unrecognized for years due to racial bias, political factors, or international lines. One powerful example is William Henry Johnson, a member of the first African-American U.S. Army unit to engage in combat during World War I.

Henry Johnson enlisted in the New York National Guard

Little is definitively known about Henry Johnson’s early years—even he was uncertain about his exact birthdate. He believed he was born on July 15, 1892, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, but official records list varying dates. As a teenager, he found work as a railway porter, hauling baggage and freight.

In the summer of 1917, Johnson enlisted in the U.S. Army after hearing that the 15th Infantry Regiment of the New York National Guard—an all-Black regiment—needed volunteers. Alongside his fellow soldiers, he deployed to France, arriving in January 1918 to join the fight on the Western Front.

Assigned to the French Army’s 161st Division

From the get-go, the eager regiment – at that point renamed the 369th Infantry Regiment and later becoming known as the “Harlem Hellfighters” – was relegated to menial tasks, such cleaning and moving goods. They were temporarily assigned to the 161st Division of the French Army by Gen. John J. Pershing. It’s believed the reason was that Pershing wanted to give African-American soldiers a chance to advance in leadership, which they couldn’t do in the segregated US Army.

The French Army had no such issue and gladly accepted the men as reinforcements, kitting them out with equipment. Johnson and his regiment were deployed to Outpost 20, near the Argonne Forest.

A nighttime raid was Henry Johnson’s chance to be a hero

On the night of May 14, 1918, Henry Johnson had no idea he was about to face the battle that would define his legacy. He and fellow soldier Needham Roberts were stationed on guard duty at the edge of a forest, with their shift scheduled to end at midnight.

Two replacement troops arrived, but Johnson quickly realized they were too inexperienced to handle the post. Instead of clocking out, he chose to stay and back them up. Roberts returned to the trench to get some rest, leaving Johnson to keep watch. Not long after, he began hearing troubling sounds coming from the woods—the rustle of movement and the distinct click of wire cutters slicing through barbed wire in the dark.

German troops attack

Out of nowhere, a group of German soldiers ambushed Henry Johnson and his comrade, Pvt. Robert S. Roberts, under the cover of darkness. As the enemy closed in, Roberts, calling for assistance, was hit by shrapnel, making him unable to continue fighting. Despite his own injuries, Johnson refused to give up. He kept the fight going, passing hand grenades to Roberts, who bravely threw them at the advancing Germans.

When the grenades ran out, Johnson grabbed his rifle, continuing to fend off the enemy even as he suffered wounds to his side, head, and hand. When the rifle malfunctioned, he used it as a blunt instrument, swinging it at the attackers.

As the battle raged on, Johnson sustained a severe blow to his head. Though dazed, he quickly rose to his feet and drew his 14-inch bolo knife. With swift and powerful strikes, he killed one German soldier instantly. Seeing the enemy attempt to drag away the injured Roberts, Johnson charged forward, wounding one of the Germans and forcing the rest to retreat in fear.

Johnson saved him and Roberts’ lives

After an hour of fierce fighting, reinforcements showed up, forcing the Germans to pull back. Johnson’s extraordinary courage guaranteed that both he and Roberts made it through, with quick medical care provided for their injuries.

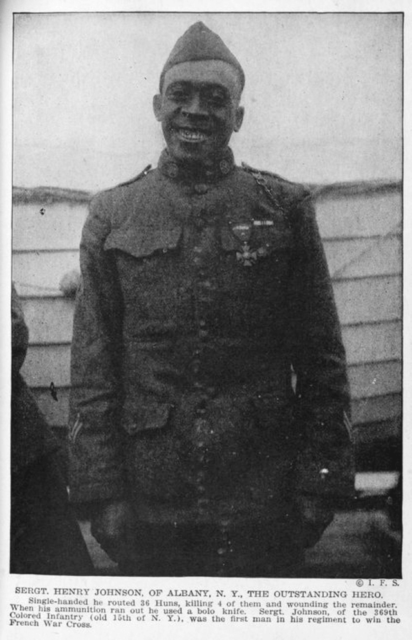

As the first light of dawn lit up the scene, the aftermath of the clash became visible: their wounds, their gear, and four fallen German soldiers. Johnson is said to have wounded another 25 to 30. His heroic stand quickly became the talk of the town, earning him a promotion to sergeant and the moniker “the Black Death.”

Awarded the Medal of Honor nearly a century later

For his efforts, the French awarded Henry Johnson the Croix de Guerre, one of their highest awards, before sending him back to the US. At the end of the First World War, the Harlem Hellfighters participated in a victory parade, with Johnson upfront. Still, they were not allowed to parade alongside the White troops.

After such an ordeal, many soldiers would return home to a hero’s welcome, which Johnson did, to an extent, but it was a bittersweet achievement. Many publications quickly glossed over his race, or avoided mentioning it at all. He gave his all and returned to a country celebrating his efforts while still regarding him as an inferior citizen.

More from us: John Simpson Kirkpatrick: The ‘Man with the Donkey’ in Galipoli

The final years of Johnson’s life mirrored the first, slipping into obscurity after the war, while receiving disability payments from the US government. It remains unclear how much his injuries affected his later life and job opportunities. He passed away on July 1, 1929 of myocarditis. The full extent of his actions weren’t appreciated until he was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart in 1996 and the Medal of Honor by then-US President Barack Obama in 2015.