Shortly before 2:00 AM on October 31, 1920, Frederick Banting woke up from a dream that would change the lives of millions. He quickly scribbled down 25 words that became the blueprint for the discovery of insulin. While Banting’s discovery is the focal point of his legacy, he also saved lives during both World Wars!

From serving as a medic in France during World War I to conducting research on the first g-suit for fighter pilots in World War II, Banting’s military service speaks to his selfless nature.

Frederick Banting’s early life and service during World War I

Frederick Grant Banting was born on November 14, 1891 in Alliston, Ontario, Canada. In 1914, he twice attempted to enlist for service overseas, but was denied both times due to his poor eyesight. He was finally allowed to a year later, due to the increasing need for doctors on the front.

After spending the summer training, Banting returned to school and was fast-tracked through the program at the University of Toronto. After recieving his medical degree in 1916, he joined the Canadian Medical Army Corps.

Banting was wounded during the Second Battle of Cambrai. Despite his injuries, he spent 16 hours tending to other wounded soldiers, until another doctor ordered him to stop. For his actions, he was presented with the Military Cross, the second highest honor awarded in the British Empire.

The discovery of insulin

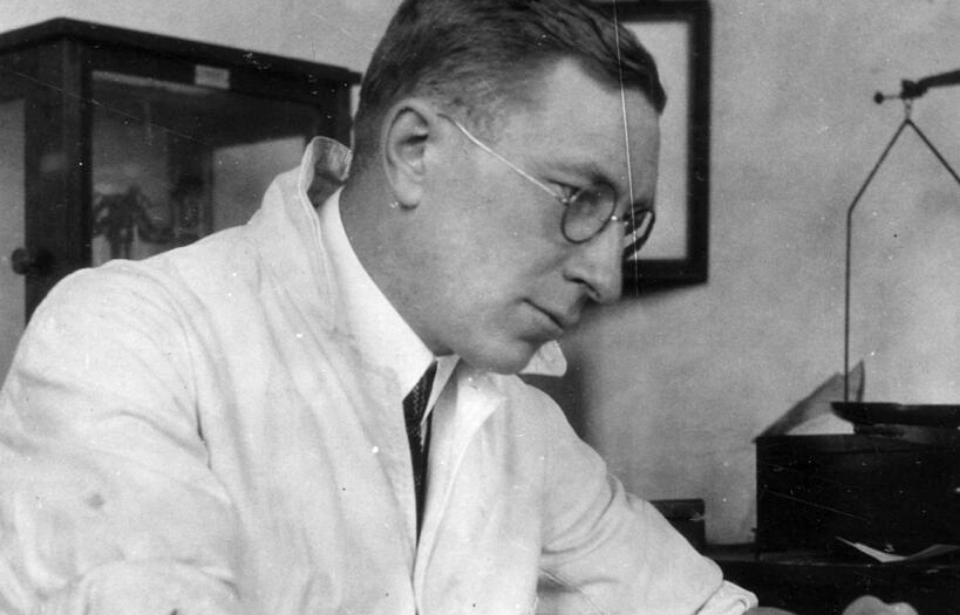

Frederick Banting moved to London, Ontario, purchased his first home and opened a private medical practice. However, he struggled to make ends meet and took a job as a professor at the University of Western Ontario, teaching anthropology and orthopedics. He also lectured in pharmacology at the University of Toronto from 1921-22.

One October night, while preparing for one of his classes, Banting was reading about the pancreas. Several hours later, he awoke with an idea that led to the discovery of insulin.

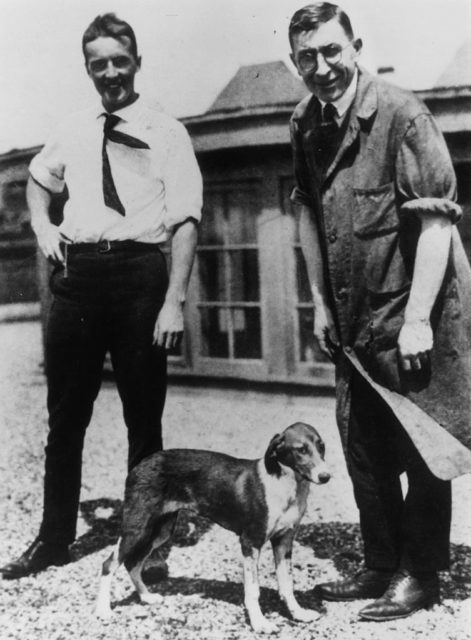

Banting enlisted the help of doctors John Macleod, James Collip and Charles Best to explore his hypothesis. After successfully isolating and identifying insulin, clinical trials began.

One patient of Banting’s, a four-year-old boy named Teddy Ryder, began treatment for diabetes after two years of following a strict starvation diet. After receiving insulin, he was finally able to live a normal life. He wrote to Banting, “I am a fat boy now and I feel fine. I can climb a tree.”

Ryder was just one of the countless children whose lives were forever changed by insulin.

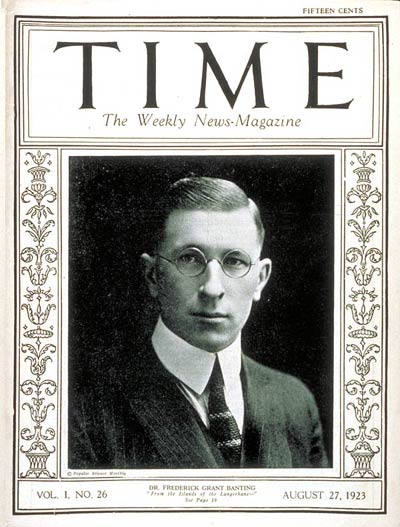

In 1923, Banting and his team of researchers were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work. To this day, he remains the youngest person to be awarded a Nobel Prize, at just 32 years old. In 1934, he was knighted by King George V and received the title of Sir Frederick Banting.

A medical pioneer during World War II

In the early days of the Second World War, Frederick Banting became interested in medical research that could be applied to warfare. He was promoted to the rank of major and became Canada’s Chief Medical Liason with British scientists, helping to develop new medical technologies.

Due to his research, the Canadian government barred him from serving on the frontlines.

In 1940, the first tests of the Franks Flying Suit took place. It was named for Dr. Wilbur Franks, one of Banting’s mentees. Banting was part of the team that created the Franks anti-gravity suit, which was geared toward solving the issue of aviator “blackout” while conducting sharp turns and steep dives. This provided the basic framework for modern-day g-suits.

Banting also tested his research on himself, including a time when he deliberately burned himself with mustard gas to learn how to counteract its effects. He advocated his concerns about biological and chemical warfare to the British cabinet, which eventually led to the creation of the Microbiological Research Establishment.

In February 1941, Banting planned to fly from Newfoundland, Canada to the UK to continue his research as Chief Medical Laision. He boarded a Hudson bomber, but soon after takeoff the oil cooler failed, leading the aircraft’s radio and both engines to fail. The pilot attempted to land the plane, but it clipped some trees and “was brought down only [meters] away from a potentially safe landing place.”

Of the four onboard the bomber, two died upon impact. While the pilot and Banting survived, the doctor, wounded and “delirious,” wandered away from the wreckage and died of exposure before help could arrive. He was just 49 years old.

Frederick Banting’s enduring legacy

Frederick Banting’s legacy lives on through his research. Today, 37.3 million Americans have diabetes – about one in ten people. Without insulin, those lives would be cut short. One hundred years after its discovery, insulin remains one of the most effective treatments for diabetes.

At the Banting House National Historic Site in London, Ontario, the Flame of Hope burns day and night. First kindled by the Queen Mother in 1989, it stands as a symbol of hope that a cure for diabetes will be found and the flame can be extinguished.