Not the first war dogs

Dogs have long played a role in warfare, but it wasn’t until World War II that the U.S. began officially training dogs for combat duties. Between 1943 and 1945, the Marine Corps began preparing dogs—especially Doberman Pinschers—for service in the Pacific, where they took on crucial responsibilities like carrying messages and guarding camps. Their effectiveness on the battlefield quickly earned them a place as essential military assets.

Use as tracking dogs in Vietnam

Labrador Retrievers were one of the dog breeds used in Vietnam, mainly for tracking. They were trained to alert their handlers to snipers, tripwires, and hidden weapons. Vietnam War veteran Rick Claggett explained that they were especially good at following blood trails. A typical Lab team was made up of the dog, its handler, a cover man, the team leader, and a visual tracker, and they were sent out when troops needed to find a wounded enemy or a missing person.

Labradors were chosen over other breeds like Beagles and Bloodhounds because they made less noise.

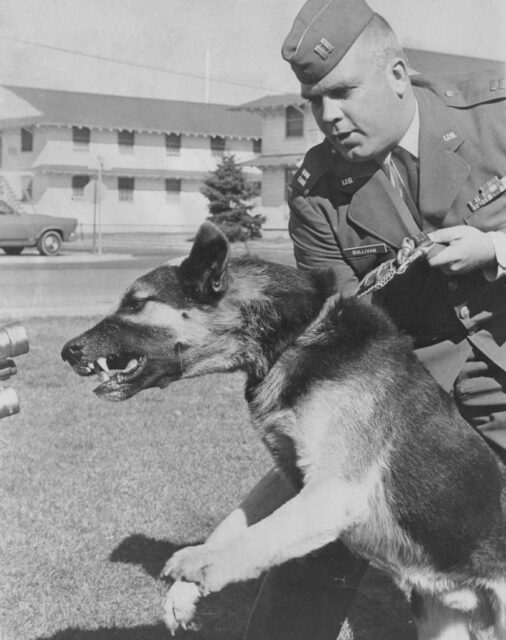

In Australia, K9 units were created using 11 shelter dogs adopted from Sydney. These dogs were named after Roman emperors and were expected to serve in Vietnam for three years. While they sometimes worked with American troops, the main breed used by the Australians was the German Shepherd.

Sentry and scouting duties

During the Vietnam War, military dogs demonstrated remarkable versatility, undertaking a variety of important roles such as sentry duty, scouting, mining, tunneling, and tracking. Rick Claggett, who worked with Big Boy, one of these expertly trained canine scouts, recalled their primary task: leading patrols through fields. These dogs were meticulously trained to detect booby traps and ambushes by scent, a skill that made their position at the forefront of such missions particularly dangerous. According to Claggett, this role carried the third-highest mortality rate during the conflict.

Sentry dogs were deployed to patrol the perimeters of U.S. outposts, acting as the first line of defense against enemy forces. German Shepherds were also used in water patrols, using their keen senses to detect enemy soldiers concealed underwater, ready to attack amphibious craft. The exceptional effectiveness of these teams made them valuable targets for Viet Cong guerrillas, who offered bounties for both the dogs and their handlers, even going so far as to attack their kennels to claim the rewards.

Nemo A534

The connection between military dogs and their handlers runs deep, and few stories show that bond better than the one between Nemo A534 and Capt. Robert Throneburg.

On December 4, 1966, while patrolling Tan Son Nhut Air Base, Nemo sensed something wasn’t right. Moments later, he alerted Throneburg to Viet Cong fighters hiding nearby. The pair charged into action, taking down two enemy soldiers—but both were seriously wounded in the process. Nemo was shot in the face, the bullet entering below his right eye and exiting through his mouth. Throneburg was shot twice in the shoulder.

Even with his severe injuries, Nemo refused to abandon his handler. He crawled over to Throneburg and lay on top of him, growling at anyone who came near until help arrived. Thanks to Nemo’s protection, medics were able to get Throneburg to safety. For his courage, Throneburg received the Bronze Star with Valor and two Purple Hearts. Nemo was brought back to the U.S., where he retired and became a recruiting dog—continuing to serve his country in a new way.

Man’s best friend

These dog/handler teams were invaluable to the war effort in Vietnam. They were credited with saving the lives of around 10,000 servicemen, thanks to their various roles in the conflict. James Mulligan handled scout dog Rickey, who “never walked our patrol into an ambush or any booby traps. He alerted on 45 ambushes, five in one day.”

While these actions were appreciated by the men that served alongside them, these dogs weren’t made a priority when the war came to an end. Of the roughly 5,000 that served, around 232 were killed in action (KIA) and another 200 were assigned to posts outside of the US. The remainder were either left in the hands of the Vietnamese or abandoned. At least 2,000 were simply euthanized.

The US government viewed them as “equipment” and didn’t want to fund their trips home. Having built such strong bonds, many soldiers wanted to bring their comrades back to the US with them, but were still told no, despite repeated appeals to Congress and the press.

More from us: Battle of Khe Sanh: The Siege That Shook America

The service performed by these canines never went forgotten, and there are countless interviews with veteran handlers who still remember their partnerships fondly. In 2019, they were publicly remembered when the Vietnam War Dog Team Memorial was unveiled at Motts Military Museum, Inc. in Ohio.