The USS Grayback (SS-208), lost in the Pacific during World War II, remained hidden beneath the waves for nearly 75 years. For decades, her final position baffled researchers—until modern search efforts uncovered the submarine deep in the Philippine Sea, more than 100 nautical miles from the Navy’s originally reported coordinates.

The discovery finally brought long-awaited closure to the families of the 80 sailors who never returned, transforming a decades-old mystery into a solemn memorial. Today, the Grayback’s resting place stands as a powerful tribute to their bravery and a preserved chapter of naval history for future generations.

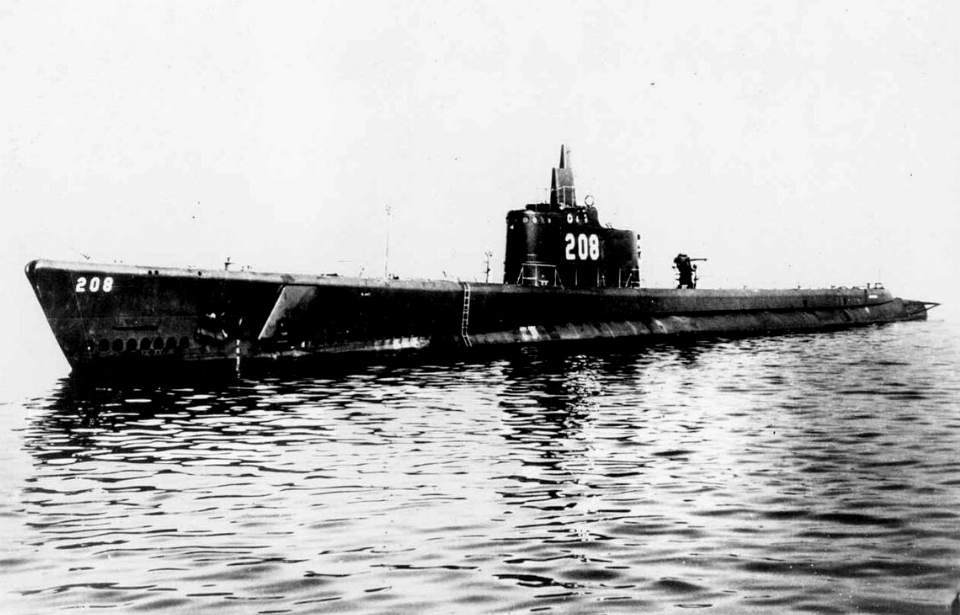

USS Grayback (SS-208)

The USS Grayback (SS-208) was commissioned on June 30, 1941, under the command of Lieutenant William A. Saunders. As a Tambor-class submarine, she embodied the latest advances in undersea warfare, built to withstand the grueling distances and operational demands of the Pacific Theater during World War II.

Designed for endurance and firepower, Grayback featured four General Motors V16 diesel engines paired with four General Electric high-speed electric motors and dual 126-cell Sargo batteries. This configuration could reach surface speeds up to 20.4 knots and submerged speeds of 8.75 knots, with an impressive range of 11,000 nautical miles at 10 knots. At minimal power, she could remain submerged for as long as 48 hours, allowing extended stealth missions behind enemy lines.

Her offensive and defensive armament was formidable: ten 21-inch torpedo tubes with 24 torpedoes, a three-inch deck gun for surface engagements, and 40 mm Bofors plus 20 mm Oerlikon cannons for anti-aircraft protection. Manned by a crew of 60—six officers and 54 enlisted sailors—Grayback quickly proved to be a compact but highly capable asset within the U.S. Navy’s submarine fleet.

USS Grayback‘s (SS-208) service during World War II

Following the US entry into World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the USS Grayback began to see action. Originally commissioned into the Atlantic Fleet, she was 20th in total tonnage sunk by American submarines, taking out 14 enemy ships (63,835 tons). She was also awarded eight battle stars for her service throughout the conflict.

In February 1942, Grayback departed from Maine for Hawaii. The submarine’s first war patrol took her along the coasts of Saipan and Guam, where she had a four-day standoff with a Japanese submarine. The enemy vessel fired two torpedoes at Grayback and followed her until she managed to escape. A month later, the submarine sank her first ship, the Japanese cargo vessel Ishikari Maru.

Grayback later conducted patrols in the South China Sea and St. George’s Passage, where the submarine was challenged by the bright moonlight, intense enemy patrols and treacherous waters. Despite these hurdles, the presence of her and her sister ships was instrumental in the success of the Guadalcanal Campaign, America’s first major land offensive in the Pacific.

Grayback garnered an impressive number of kills after this, and was even credited with saving the lives of six crewmen who’d survived the crash of their Martin B-26 Marauder in the Solomon Islands. While she experienced a string of bad luck during her sixth patrol, the submarine’s reputation made a turn for the better in later patrols, one of which saw her join one of the first wolfpacks organized by the Submarine Force.

Of all her patrols, it was Grayback‘s 10th that was her most successful – and also the submarine’s last.

A successful final mission in the Pacific Theater

On February 24, 1944, the crew of the USS Grayback reported sinking two Japanese cargo ships and damaging two others during its tenth war patrol. The following day, the submarine filed what would become its last report, confirming the destruction of the tanker Nanho Maru and heavy damage to the Asama Maru. With only two torpedoes remaining, Grayback was ordered to return to its base in Fremantle, Western Australia.

The submarine was expected to reach Midway Island by March 7, but it never arrived. On March 30, the Navy officially listed Grayback as missing, with all 80 crew members presumed lost.

Years later, captured Japanese records finally shed light on the sub’s fate. After attacking convoy Hi-40, Grayback launched its last two torpedoes on February 27, sinking the Ceylon Maru in the East China Sea. Shortly afterward, a Japanese Nakajima B5N torpedo bomber spotted the submarine and dropped a 500-pound bomb. According to the reports, Grayback “exploded and sank immediately.” Additional aircraft then saturated the area with depth charges to ensure the kill.

For nearly 75 years, the submarine’s resting place remained unknown—its final moments preserved only in foreign wartime documents. The eventual discovery of the wreck at last provided the closure long denied to the families of the 80 sailors who perished, bringing a silent chapter of World War II history back into the light.

Unexpected discovery within the USS Grayback (SS-208)

During the Second World War, 52 American submarines were lost, taking the lives of 374 officers and 3,131 sailors. The Lost 52 Project is an initiative dedicated to locating all 52 vessels, to bring closure to the families of those who lost their lives. Using state-of-the-art technology, the team captures images and 3D scans of the wrecks they discover to help document each submarine.

On November 10, 2019, the Lost 52 Project announced it had located the USS Grayback some 50 nautical miles south of Okinawa, roughly 1,400 feet below the surface. Her deck gun was found 400 feet away from the main wreckage. The damage the submarine had sustained appeared consistent with what was listed in the Japanese report. There was severe damage aft of the conning tower, and part of the hull had imploded. As well, the bow had broken off at an angle.

It’s a miracle they even found the wreck, considering the original coordinates translated by the US Navy were 100 nautical miles off, thanks to a clerical error that was off by just one number.

The team set up a dive team to explore the wreckage, but what they found inside overshadowed the celebratory mood around such an incredible discovery. Tim Taylor, one of the team leads, shared how he felt with The New York Times, “We were elated, but it’s also sobering, because we just found 80 men.”

Prayers of family members have finally been answered

Gloria Hurney’s uncle, Raymond Parks, was among those lost when the USS Grayback sank. He was an electrician’s mate first class. Hurney and many others had come to believe that the wreck would never be found, but the Lost 52 Project proved them wrong.

More from us: Inside a Submarine: A Glimpse Into the Lives of Those Serving Beneath the Ocean’s Surface

While Grayback‘s discovery was bittersweet, it also brought closure and peace to the families who waited 75 years to learn where their loved ones were laid to rest.