On February 9, 2001, approximately nine nautical miles south of Oahu, Hawaii, the USS Greeneville (SSN-772) was involved in a collision with Ehime Maru, a Japanese fishing trawler and high-school training ship. To demonstrate her capabilities for onboard VIPs, the Los Angeles-class nuclear attack submarine performed an emergency blow, during which she struck the Japanese ship, which sank minutes later.

Lead up to a disastrous collision

On January 10, 2001, Ehime Maru departed Japan for Hawaii. The Japanese fishing trawler, owned by the government of the Ehime Prefecture, was on a 74-day cruise to train high school students about the sea, sailing and fishing.

On February 8, Ehime Maru reached Honolulu. The following day, the USS Greeneville prepared to leave Pearl Harbor as part of the US Navy’s Distinguished Visitor Embarkation (DVE) program. The initiative saw civilians invited aboard nuclear submarines to see the vessels’ capabilities.

On previous trips, Greeneville had played host to the likes of Tipper Gore and James Cameron.

Greeneville departed Pearl Harbor at just before 8:00 AM with 16 civilians. While the submarine left on time, she soon fell behind schedule, reaching her dive point at 10:17 AM and submerging. While submerged, the VIPs were provided lunch, after which they were supposed to go to the control room and view the vessel’s capabilities. The aim was to return to Pearl Harbor by 2:30 PM.

At around 12:50 PM, Ehime Maru departed Honolulu, reaching the area where Greeneville was operational. She was picked up on the submarine’s sonar and designated “Sierra 13” (S-13). Patrick Seacrest, Greeneville’s fire control technician, determined the course, speed and range of the vessel. He also determined Sierra 13 to be heading away from Greenville.

Since the VIPs were standing in front of the Contact Evaluation Plot, Seacrest stopped updating the system on the vessel’s movements.

USS Greenville (SSN-772) collides with Ehime Maru

Before the USS Greeneville began her maneuvers, Cmdr. Scott Waddle verified there were a number of surface vessels in the area, but none were closer than seven nautical miles.

For 15 minutes, the submarine performed various maneuvers to the delight of the VIPs onboard. Once finished, Greeneville went to periscope depth to check for ships or obstacles, before performing an emergency dive and blow; she would quickly submerge to 400 feet, then surface in a matter of seconds.

The checking of the submarine’s surroundings was rushed, and while S-13 (Ehime Maru) closed in on her location, the Japanese vessel wasn’t reported; with Widdle not making any visual contacts, Patrick Seacrest thought the system must be wrong. Instead of believing the contact was 3,000 yards away and closing in, he reported the distance as 9,000 yards.

Greeneville submerged and began her ascent to the surface. Two VIPs, John Hall, CEO of an oil company, and Jack Clary, a sports writer, were allowed to operate the controls for the emergency blow. Clary sat in the helmsman’s chair while Hall controlled the air valves, both supervised by Greeneville‘s crewmen.

At 1:43 PM, Greeneville surfaced directly under Ehime Maru, causing a disastrous collision. The former’s rudder cut into the Japanese ship’s hull from starboard to port, causing the vessel to lose power and begin to sink. From periscope depth, Widdle watched as the ship stood almost vertical, sinking in a matter of minutes.

Attempting to rescue those aboard Ehime Maru

After the collision, at 1:48 PM, the USS Greeneville radioed for assistance, and the US Coast Guard began a search and rescue operation. It was decided Greeneville wouldn’t try to take survivors from Ehime Maru aboard.

At almost 2:30 PM, a Coast Guard helicopter arrived and, seeing survivors in life rafts, began a search for anyone who could still be in the water. Shortly after, two boats arrived to pick up the stranded crewmen and passengers. At the same time, the media arrived on the scene.

There had been 35 people aboard Ehime Maru, of which 26 were rescued, one with serious injuries. The other nine were missing. Despite a search by the Coast Guard, the US Navy and two Japanese civilian ships, they weren’t located.

Japanese response to the incident

After Ehime Maru sank, Japanese Premier Yoshirō Mori was informed of what had occurred. He was later criticized for his response, as he continued to play his round of golf for another hour and a half before returning to work.

Japanese media soon reported that civilians had been at the controls of the USS Greeneville, causing Japanese officials to express their concern. Foreign Minister Yōhei Kōno stated, “I cannot help but say it is an extremely grave situation if it were the case that the participation of civilians in the submarine’s surfacing maneuver led to the accident.”

American officials issue an apology to Japan

America was quick to apologize for the collision between the USS Greeneville and Ehime Maru. On February 11, 2001, President George W. Bush apologized on television, saying, “I want to reiterate what I said to the prime minister of Japan: I’m deeply sorry about the accident that took place; our nation is sorry.”

Secretary of State Colin Powell and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld also made public apologies.

Tom Foley, the American ambassador to Japan, made personal apologies to the country’s premier and emperor, while Adm. Thomas B. Fargo, commander of the US Pacific Fleet, apologized to the families of the victims. Later, Adm. William Fallon, vice chief of naval operations, went to Japan and met with family members.

The Japanese largely accepted these apologies. However, many Americans felt they’d gone too far. Writing in a column for The Washington Post, Richard Cohen said, “We’ve apologized enough to Japan.” He added that, while America had apologized excessively for the incident, Japanese officials had begrudgingly apologized for what their nation did during World War II.

Scott Waddle later visited Japan himself.

Aftermath of the collision

The USS Greeneville suffered some damage in her collision with Ehime Maru, including a single 31-foot scrape on her rudder, a 24-foot section of missing acoustic tiles and multiple dents. The repairs cost $2 million and were completed on April 18, 2002, at which point the submarine returned to active duty.

The US Navy convened a court of inquiry. It didn’t recommend a court-martial, but, instead, a non-judicial punishment. Thomas Fargo met with Scott Waddle and told him that his resignation should be expected, with him retiring on October 1, 2001.

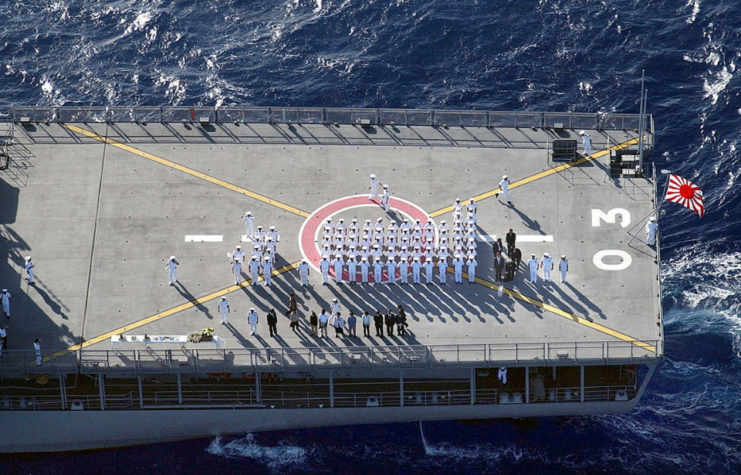

Initial dives to the wreck of Ehime Maru proved unsuccessful in finding the bodies of those who died onboard. It was decided to salvage the ship, moving it closer inshore, where more thorough dives could take place. Subsequent excursions by both Navy and Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force divers recovered eight of the nine bodies, as well as many personal items or items special to the ship.

More from us: Götheborg of Sweden: The Replica 1700s Ship That Rescued a Modern-Day Vessel in Distress

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

On November 25, 2001, Ehime Maru was raised, taken out to sea and scuttled in 6,000 feet of water.