USS Pueblo (AGER-2) prior to becoming a spy ship

Built in 1944 as a Banner-class cargo vessel (FP-344/FS-344) for the U.S. Army, the ship began its career far from the front lines. Transferred to the Coast Guard in April 1945, it served primarily as a training vessel, preparing civilians for Army service during the final months of World War II. It remained in that role until it was decommissioned in 1954 and quietly faded into obscurity.

More than a decade later, the vessel was pulled from retirement and given a new purpose. After a thorough overhaul, it reentered service as USS Pueblo (AKL-44), functioning as a light cargo ship. Additional upgrades soon followed, and the ship was reclassified as AGER-2—officially an “environmental research vessel.”

In reality, Pueblo’s scientific mission was little more than a cover. The specialized modifications had transformed the aging cargo ship into a floating intelligence platform. Outfitted with advanced signals-collection equipment, it was tasked with gathering electronic and communications intelligence for the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) and the National Security Agency (NSA). Beneath the veneer of research, the ship was now a covert tool of the Cold War, operating in the shadows as tensions with North Korea and the Soviet bloc intensified.

USS Pueblo (AGER-2) is deployed to North Korea

By 1967, the USS Pueblo had completed shakedown training and was prepared for its first espionage mission. On January 5, 1968, the ship set sail with the goal of gathering intelligence on both North Korea and the Soviet Navy. Eleven days later, the Pueblo reached the 42nd parallel, ready to patrol the North Korean coastline while staying at least 13 nautical miles away from shore.

On January 23, 1968, North Korea launched an attack on the Pueblo. The spy ship was spotted by a submarine chaser, which issued an ultimatum: surrender or face fire. Although the Pueblo tried to flee, its slower speed made it impossible to evade the threat.

The submarine chaser was soon joined by four torpedo boats, another chaser, and two Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 aircraft. Armed with only a few handguns and two M2 Browning machine guns, the Pueblo and her crew were severely outgunned. Despite this, they put up resistance for as long as possible to prevent the North Koreans from boarding.

North Korea captures the USS Pueblo (AGER-2)

When the USS Pueblo arrived near the port city of Wonsan, the crew rushed to destroy as much classified information as they could. But in order to do that, the ship had to slow down, which made it an easy target.

North Korean forces began shooting at the ship with a 57 mm cannon and machine guns, hitting it and killing one crew member, Duane Hodges. Two others were injured in the attack, including U.S. Marine Sgt. Bob Chicca. Eventually, the North Koreans boarded the ship, blindfolded the crew, and tied their hands.

After being taken to shore, the captured sailors were subjected to harsh physical abuse by their captors.

American sailors were held captive for months

Signing the three A’s document

At the time of the USS Pueblo’s capture, the United States was deeply involved in the Vietnam War. Concerned that tensions with North Korea could escalate, American officials pursued a diplomatic approach to address the crisis. After nearly a year, both nations reached an agreement that allowed for the safe return of the Pueblo’s crew.

On December 23, 1968, US Army Maj. Gilbert Woodward signed a document known as the “three A’s agreement,” drafted by North Korean authorities. This agreement required the United States to acknowledge wrongdoing, apologize, and pledge to prevent similar incidents in the future.

Following this, the crew members were released and returned to the United States, while the Pueblo remained in North Korean possession. Initially displayed in Wonsan and Hŭngnam, the vessel was eventually moved to the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum in Pyongyang.

USS Pueblo (AGER-2) is still held captive

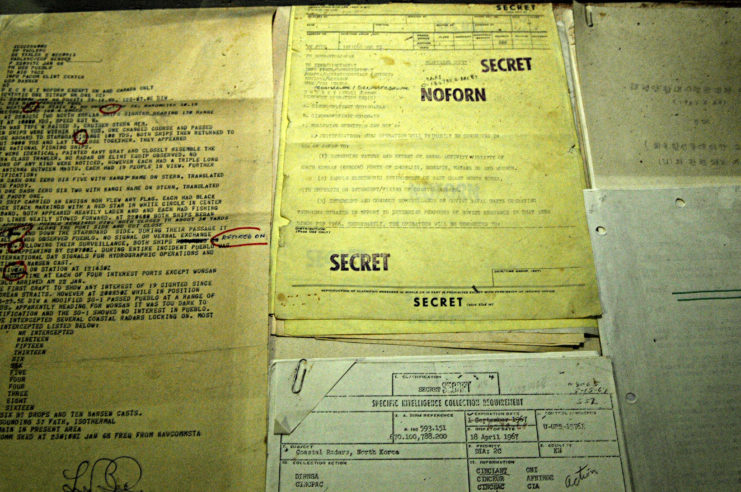

When North Korean forces took control of the USS Pueblo, they also captured 10 encryption devices and thousands of highly classified documents—marking one of the most damaging intelligence losses of the Cold War. The trove of secret material offered North Korea and its allies, including the Soviet Union, a rare window into U.S. surveillance techniques and communication codes.

Remarkably, the Pueblo is still listed as an active commissioned vessel by the U.S. Navy, despite being held in enemy territory since 1968. Now docked in Pyongyang, the ship has been transformed into a museum exhibit and a powerful symbol of North Korean propaganda. It undergoes regular maintenance and has even received commemorative paint jobs to coincide with national observances like the anniversary of the Korean War.

In response to North Korea’s ongoing defiance and a renewed U.S. designation as a state sponsor of terrorism in 2017, surviving crew members and the families of deceased sailors filed a lawsuit under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. In 2021, a U.S. court awarded them $2.3 billion in damages. Still, collecting on that judgment remains a long shot, as there are no straightforward financial links between the United States and North Korea.