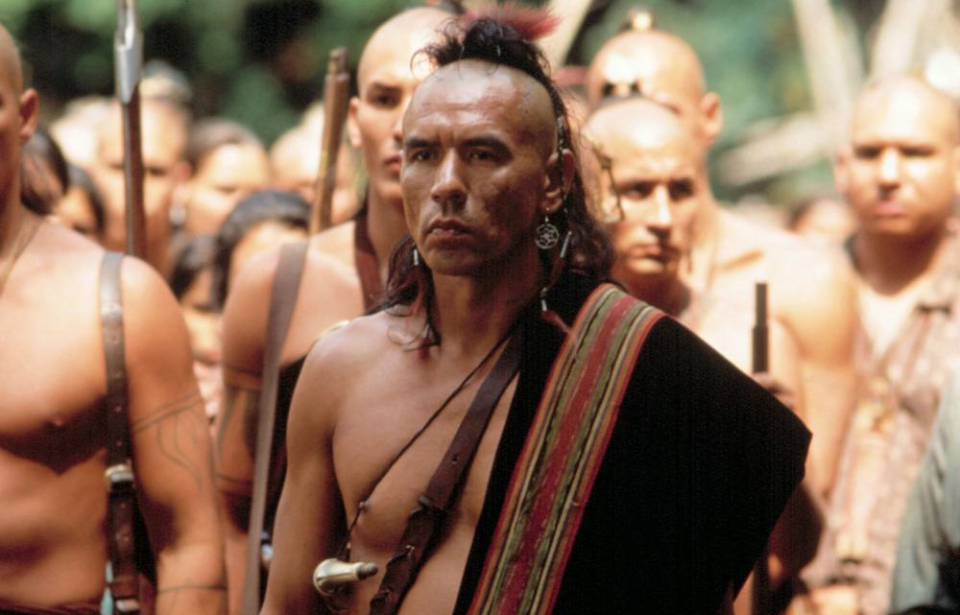

Wes Studi is widely celebrated for his powerful performances in landmark films like Dances with Wolves, The Last of the Mohicans, Geronimo: An American Legend, and The New World. His portrayals of Native American characters have been highly regarded for their depth and authenticity, earning him lasting respect in the industry.

Yet before his Hollywood success, Studi answered a different call by joining the Oklahoma National Guard. He deployed to Vietnam, where he experienced the harsh realities of war firsthand. Those formative years instilled in him a sense of discipline and resilience that would later infuse his acting with a quiet, compelling intensity—rooted in lessons learned far from any movie set.

Wes Studi’s early life

Wes Studi was born in Nofire Hollow, Oklahoma, and grew up in a Cherokee-speaking household, only learning English when he began attending elementary school. He later enrolled at the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, a federally run boarding school where he graduated in 1964. At Chilocco, students were required to pick a trade for vocational training, and Studi chose dry cleaning as his specialty.

At the age of 17, Wes Studi enlisted in the Oklahoma National Guard, committing to the standard six-year term of service that was customary during that era. In an interview with Military.com, he shared that his reason for enlisting was that he “got to march around our school grounds and had a paycheck as well.”

Wes Studi is deployed to Vietnam

While serving with the Oklahoma National Guard, Wes Studi underwent both basic combat and advanced individual training at Fort Polk, Louisiana. During his time there, he decided he wanted to serve in the Vietnam War after hearing stories from those who had recently returned. With only one year left in the National Guard, he volunteered for active duty.

Studi was deployed overseas with A Company, 3rd Battalion, 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, serving with them for 12 months. He later recalled arriving in Vietnam just before the “Mini-Tet” Offensive, when the Viet Cong and Northern Vietnamese Army (NVA) launched an attack on Saigon following the Tet Offensive.

He shared with Military.com, “I actually didn’t partake [in] all of the fighting that was going on there in Saigon. I think they decided to leave most of us who were new in country there at the French Fort, even though the company was very active in the defense of Saigon at the time.”

The fort, situated near the Mekong Delta, was where most of the 9th Infantry Division’s missions were carried out. Located deep in Viet Cong-controlled territory, they spent much of their time defending the area against enemy forces.

Returning stateside

Like countless Vietnam veterans, Wes Studi faced significant challenges when transitioning back to civilian life. His time in combat had instilled a constant sense of vigilance—an instinct that didn’t simply disappear once he was home. Adding to that difficulty was the widespread public resentment many veterans encountered during that era. Instead of receiving a hero’s welcome, Studi, like many of his peers, returned to a country that often met him with negative attitudes and hostility. Reflecting on that time, he once said, “When I came back, I had to deal with being called a baby killer, with how soldiers were treated when they returned from there.”

During this difficult time, Wes Studi discovered new meaning through two powerful pursuits: activism and acting. Driven by his experiences as a Vietnam veteran, he became involved with Vietnam Veterans Against the War, an influential group established in 1967 that empowered returning soldiers to speak out against U.S. involvement in Vietnam. This organization played a key role in shaping the anti-war movement of the period.

In 1973, Studi’s commitment to activism intensified when he participated in the 71-day Wounded Knee Occupation—a protest that honored the historical Massacre at Wounded Knee of the Lakota people and highlighted ongoing Native American struggles for justice. Concurrently, he began to explore acting, enrolling at Tulsa Community College, a decision that would eventually lead him to a celebrated career in film.

Wes Studi’s decades-spanning acting career

When Wes Studi began his acting career, he often found himself in minor roles, where his characters were even nameless. However, as time went on, he became part of a significant shift in Hollywood, where Native American characters evolved beyond stereotypical depictions. Rather than being cast as simplistic or one-dimensional foes, these characters began to be portrayed with greater complexity and depth.

Throughout his career, Studi expanded his range, leaving his mark in both film and television. His compelling performances and enduring contributions to the industry were recognized in 2019 when he was awarded an Academy Honorary Award, making him the first Native American actor to receive such an honor.

Studi’s service in Vietnam profoundly influenced his approach to acting, particularly in how he infused his roles with authenticity and emotional depth. Drawing from his personal military experiences, he brought a unique sense of realism to his characters. In a 2017 interview with GQ, Studi discussed his role as Chief Yellow Hawk in Hostiles, where he compared the evolving relationship between his character and Christian Bale’s Captain Joseph J. Blocker to his own shifting perspective on the Viet Cong during the war. Initially seeing them as enemies, Studi later came to recognize their humanity, mirroring the dynamic between the two characters in the film.

He said, “I have a great respect for the Viet Cong, not only because of their prowess and their ability to fight… But I have a great respect for them, not only because they’re great warriors. They’re probably more like me than the people I was fighting for, you know? I think that was sort of what fed the kind of feelings that existed between Yellow Hawk and Bale’s character.”

Veteran activism

Beyond his successful acting career and military service, Wes Studi is deeply involved in supporting veterans. In an interview with U.S. Veterans Magazine, he shared that he regularly attends Vietnam Veterans of America conventions and visits various military bases. “It was drummed into us to take care of yourself and take care of your buddies,” he said.

More from us: Before Becoming An Actor, Adam Driver Served in the US Marine Corps

Studi believes this mindset should continue among veterans and the public. “War may be hell – but peace can be a killer, too,” he explained. “It is absolutely incumbent on the nation to take care of our veterans. Interventions – be it counseling or acting or farming or anything else – need to get out ahead of the pain and tragedies.”