From the start of the 19th century, the race was on to create steam-powered navies. This would eventually take the world’s fleets from wooden sailing ships to the high-tech vessels we know today. But the process of change was slow, and Great Britain, the greatest naval power of the era, opposed this advance in technology.

The Arrival of Steam

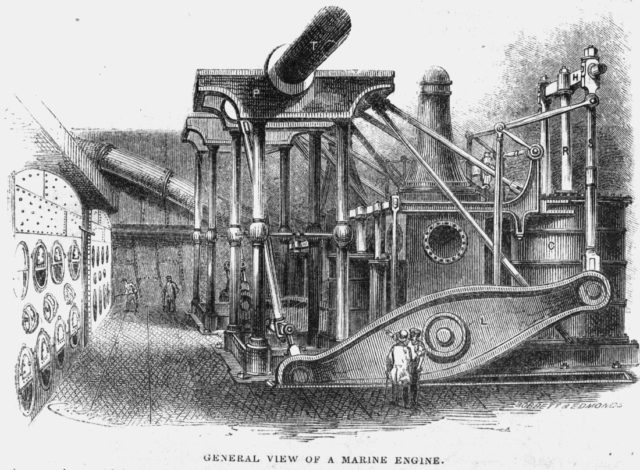

Steam power was developed in the 18th century, as the first steps were taken in the industrial revolution. Initially used for processes such as powering factories and pumping water out of mines, steam engines became increasingly compact and powerful, in particular through the work of Scottish inventor James Watt.

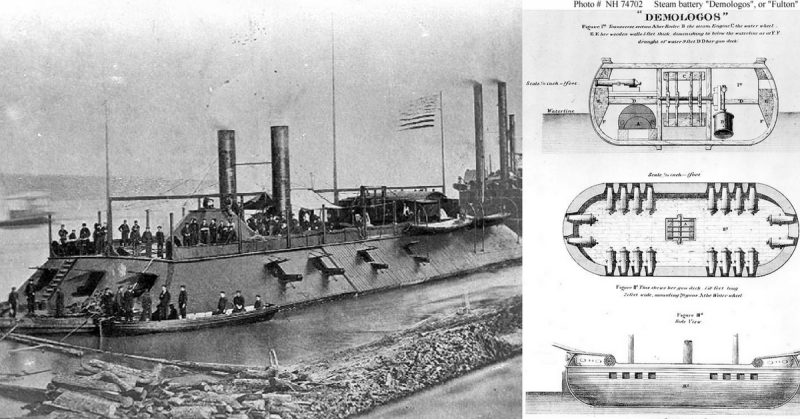

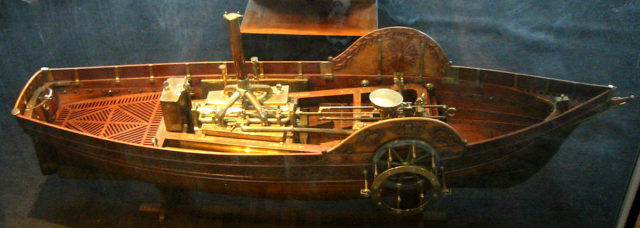

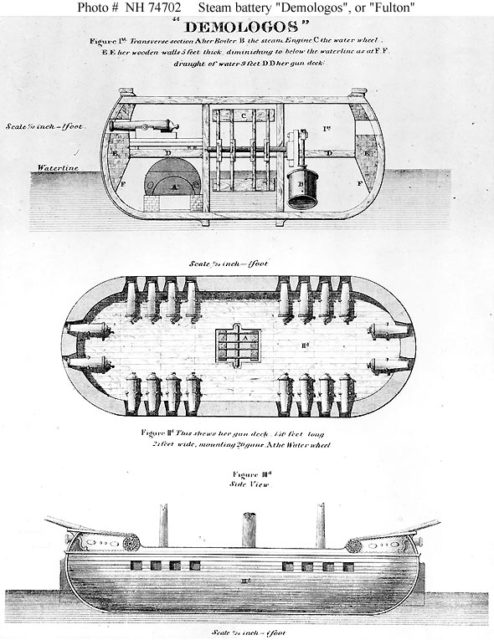

The USA was the first country to produce a steam-powered warship. The Demologos was developed to solve difficulties fighting Britain during the War of 1812. Twin-hulled and driven by internal paddle wheels, she was little more than a floating artillery platform. Utterly unseaworthy, she was still able to help defend the harbor at New York.

Tactical Advantages, Strategic Setbacks

The move to steam power brought some huge advantages.

In the past, navies had been forced to choose between maneuverability and speed. Oared galleys could be maneuvered easily and sailed in any direction, irrespective of the wind. Sailing ships, on the other hand, became faster and more powerful but were dependent upon the weather.

The 16th century had seen galleys left behind, as sailing technology improved. So, when steam engines once again freed ships from dependence on the weather, they regained freedom of maneuver for the first time in hundreds of years.

Steam ships were more tactically maneuverable. Their fighting style was not dependent upon seizing the weather gauge – by gaining the best position in a fight relative to the wind. They could also travel faster across oceans.

They had one major drawback, though, compared with sailing vessels – their reliance on coal. This tethered navies to refueling depots and made fuel supplies a factor in naval strategy. When the British refused to provide the Russians with refueling opportunities in the Russo-Japanese War, the Russian fleet found its maneuvers in the Pacific limited. It was forced to carry enough coal for the whole campaign.

Slow Adoption

Despite the advantages it could bring, many navies were slow to adopt steam power. The French, then a major global power, did not start building steam warships until the 1840s, and even then did so on a small scale. But perhaps the most surprising example was Great Britain.

The British had an empire that spanned the globe, one in which naval power was absolutely vital. Their enormous fleets were supported by some of the world’s biggest military docks and crewed by the finest sailors on the seas. With those docks and its vast industrial capacity, Britain was in the best position to start creating steam ships. Many refinements in steam engines, including those of James Watt, had even come out of Britain.

Yet the British were afraid of this change, believing that it might damage their dominance. If steam ships were widely adopted, then all of their superior sailing power would become obsolete. Their well-practiced ability to seize the weather gauge would become useless. Many of their advantages would disappear.

As the British Admiralty said in 1828, “the introduction of steam is calculated to strike a fatal blow at the naval supremacy of the Empire.” And so the world’s greatest naval power, far from pushing for better technology, did its best to hold it back.

Ruling the Waves

Eventually, though, the British realized that they had to change. If they were going to continue ruling the waves, then it was preferable to be in the lead technologically than to cling to a glorious but outdated past.

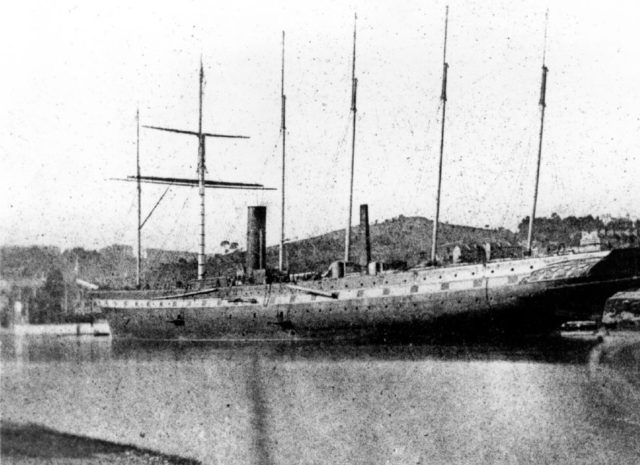

One early sign of the shift in thinking came in 1843 when the British steamer the Great Britain crossed the Atlantic. It was the first screw-equipped ship to do this. Screw-driven ships were a major step forward. Screws were less vulnerable and unwieldy than the paddle wheels that were used by early steamships such as the Demologos. Britain was engaging with the latest technology, developing the skills to make the best steam ships.

One motivation to do this was because the French were making progress with their ships. Franco-British relations were tense throughout most of the 19th century. Britain had held out against Napoleon, only the latest in many wars between these neighbors. They were vying for dominance both in Europe and abroad. Though they would end up on the same side when modern war finally came in 1914, many expected the opposite to happen. So when the French launched La Gloire, a steamship made of wood but clad in iron, the British had to try to beat them to the next step. The result was the launch in 1860 of HMS Warrior, the first all-iron, steam-powered, shell-firing ship.

Using the Industrial Advantage

Having entered the race toward a steam fleet, the British now made use of their industrial advantages. As the leading nation of the industrial revolution, and the owner of vast shipyards, the British were able to make swift advances.

In 1897, at the Jubilee Naval Review, the steam launch Turbinia raced through the lines of other British ships at an extraordinary 34.5 knots. Throughout the century, British ships continued to be fitted with masts, but these were increasingly secondary to steam engines.

Britain’s vast empire was the reason she needed a steam-powered navy. That empire also helped to keep the navy moving. With sources of coal and storage bases scattered across the globe, the British were in the best position to refuel their fleets. Having for so long resisted the move to steam, they now found it working to their advantage.

Britain had been slow to move to steam-powered warships but in the end, she would benefit hugely from them.