In the brutal, hard-fought wars of the Middle Eastern crusades, few figures stand out as brightly as Saladin. Rallying Muslim forces, he drove back the crusaders, faced one of their greatest leaders in the form of King Richard of England, and despite setbacks clung onto the most important city in the region – Jerusalem.

The Rise of Saladin

A Kurdish warrior who gained his early experience fighting in Egypt, Saladin was an outsider in the Turkish-dominated Muslim military, but his leadership skills let him rise to great power. In 1169 he was made a vizier, and in 1171 he overthrew the last Fatimid caliph, restoring Sunni Islam in the name of the Abbasids. The legitimacy of his power was reinforced by his religious orthodoxy and claims to pursue holy war.

Some Muslims saw him as an opportunist. From 1174 to 1186 he spent nearly three times as much time fighting fellow Muslims as he did Christians. He conquered the Seljuk Turks in 1179, Aleppo in 1183, Mosul and Diyarbakir in 1185-86. These wars created a power base that allowed him to turn massive force against the crusader states created by European warriors in the Middle East.

Divisions among the leaders of the crusader states prevented them from acting decisively during Saladin’s rise to power. With no fresh crusades coming from the west, and his opponents fractured, he had breathing room to learn to fight these opponents through a series of battles.

In most of these confrontations, Saladin had the larger force, including superior numbers of cavalry. Whenever possible, he withdrew the centre of his line, enveloped the advancing enemy with the wings of his force, and surrounded them.

This did not always work, as at Darum in 1170 where King Amalric of Jerusalem held a defensive line. There were setbacks, such as Reynald de Châtillon’s rout of the poorly deployed Muslim forces in 1177.

But Saladin learned from his errors. He built a strategically strong position, consolidating gains and rebuilding his fleet. Raids into Christian territory in the 1180s drew out his opponents’ forces, allowing him to defeat them in the field and then besiege their poorly defended castles.

Conquering Jerusalem

The campaigns of 1187 to 1190 were the high point of Saladin’s success, as he conquered the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Drawing on forces from recently taken Muslim lands, Saladin made a strong raid into the heart of the kingdom in 1187. This was made easier when Count Raymond of Tripoli, previously regent of the kingdom, let him through the count’s lands. Raymond had fallen out with King Guy of Jerusalem and was initially happy to see Saladin attack him. 140 knights under Gerard de Ridefort were wiped out attacking 7,000 of Saladin’s men at the Springs of Cresson, and it was only then that Raymond joined with Guy to fight the Muslims.

On the 2nd of July, 1187, Saladin besieged Tiberias, and Guy marched to relieve it. Saladin held the best water sources in the area and harassed the Christians as they advanced. Forcing them to a halt, he surrounded them and cut them off from water. On the 4th of July, Guy’s desperate forces tried to break out towards the springs at Hattin. Under heavy arrow fire and choking on smoke from fires set by Saladin’s men, they were unable to break through and fought a last stand. Most of the nobility, including King Guy, were captured.

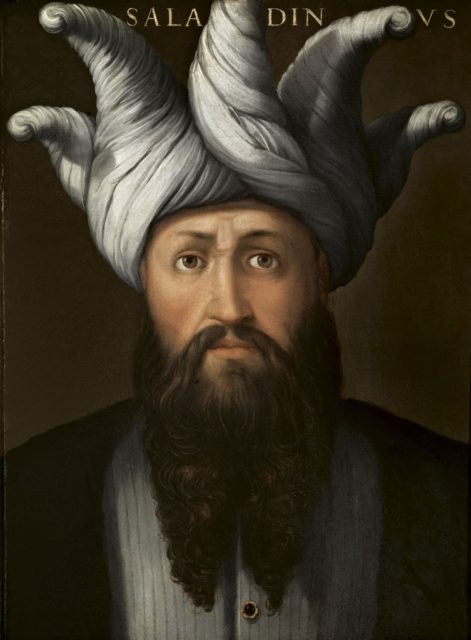

With Saladin ascendant, the cities of the region swiftly fell to him. Acre surrendered within days. Sidon and Beirut were captured. Ascalon surrendered thanks to the influence of King Guy, while the captive Templar Master ordered Gaza to give in. Jerusalem, symbolically vital to both sides, was taken in the space of two weeks.

Ports, towns, and castles fell to siege, subterfuge, or negotiation. But importantly, Antioch and the strategically important port of Tyre held out. With his troops wanting to stop and enjoy their spoils, and Muslim leaders fearful of his growing power, Saladin had reached his limits. He negotiated a truce with Bohemond of Antioch just as the city looked primed to fall.

The Third Crusade

The fall of Jerusalem finally motivated European rulers to intervene once more in the Holy Land. From 1189, forces gathered under the German Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, the French King Phillip II, and King Richard I of England. Supply problems, other distractions, and the death of Barbarossa meant that it was 1191 before a substantial army had gathered, and of the three rulers, only Richard remained to lead it.

Richard conquered Cyprus, ensuring supply routes for the crusader states, reconquered Acre within two months of his arrival, and entered into negotiations with Saladin. When these proved fruitless, he massacred 3,000 prisoners to make clear the seriousness of his purpose, and then set off south towards Jaffa.

This was the moment when Richard showed himself a worthy opponent for Saladin. By sticking to the coast, he ensured that his army could be supplied by sea and that it could not be attacked on the western flank.

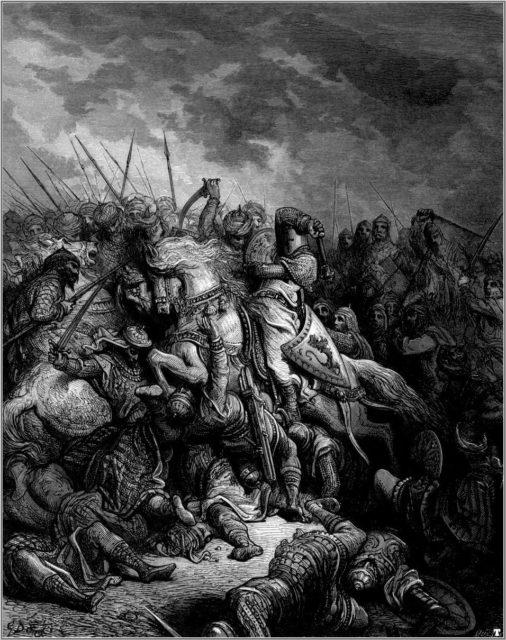

Saladin tried to break this strategy. At Arsuf on the 7th of September, 1191, he blocked the crusaders’ path. While the crusaders appeared to weaken in the early stages of the battle, the impatience of knightly cavalry for once worked in their favour. An impetuous charge broke through the Muslim lines and Richard seized the opportunity, using more heavy cavalry charges to break Saladin’s force.

Arsuf was not as decisive as Hattin, but it gave Richard the advantage and he steadily retook territory Saladin had gained. Despite this, Saladin was not beaten. By gathering a strong army and poisoning strategically important springs, he was able to stop the crusader advance and hold onto Jerusalem. Richard could not get the support he needed to attack Saladin’s supply base in Egypt, and neither fighting nor negotiation created decisive results for either side. On the 9th of October, 1192, Richard left the Holy Land.

By now, Saladin had fallen ill, and he died of a fever on the 4th of March, 1193. His conquests had been partly undone by Richard, and would unravel following his death. But he had shown that the crusaders could be driven back and that the region could return to Muslim hands.