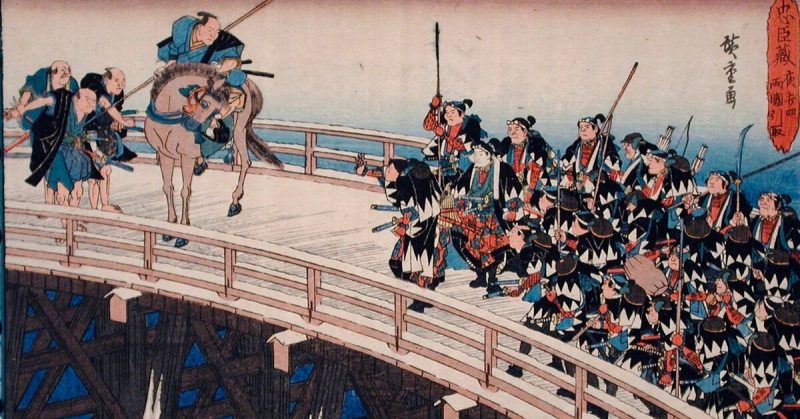

Feudal Japan is remembered as the era of the samurai. Like the knights of feudal Europe, they were the expensively equipped warrior aristocracy. They were, however, just one of numerous different types of warrior distinct to that period.

Samurai

Emerging late in the first millennium AD, the samurai were a warrior aristocracy. As landowners and leaders of society, even the lowliest of samurai, were wealthier and more privileged than most Japanese people.

The samurai began as horse archers which influenced their equipment even as they shifted towards their role as swordsmen. Their right arm was initially less armored than the left, leaving it free to draw arrows and the bowstring.

Over time, their quiver at the right hip was abandoned. Their armor became sturdier and symmetrical as they shifted to close quarters fighting using carefully crafted swords.

Samurai fought with a variety of weapons, including spears and clubs. Their most common and iconic weapons were the paired swords of the long katana and the shorter wakizashi, both curved and crafted to deadly sharp edges.

Almost all commanders were a samurai. They were Japan’s military, political, social, and economic elite. A feudal hierarchy of land ownership meant each samurai owed military service to another, right up to the Emperor.

In battle, samurai provided the elite core of fighters in most armies and shock troops for cavalry and infantry charges.

Sohei

From the 11th through to the 16th centuries, the samurai sometimes fought alongside or against another group of elite warriors – the sohei.

The sohei were Buddhist warrior monks. Several monasteries maintained armies of them. They provided protection during times of strife and were used during disputes with other temples or samurai lords. The most famous and feared contingent were based at the Enryaku-Ji, the main temple on Mount Hiei.

Sohei were usually less equipped than samurai. They wore the armor of regular infantry over their monastic robes, often with an outer robe over the top. Knotted towels or cowls covered their shaven heads. Their traditional weapon was the naginata, a bladed polearm.

The sohei could be valuable allies for samurai lords, but they could also be troublesome. They used their military power to assert the independence of their monasteries in the face of secular authority.

Ikko-Ikki

The 15th century saw the rise of another fearsome group of religious warriors, the Ikko-Ikki.

The Ikko-Ikki were Jodo-Shinshu Buddhists, following an offshoot of Pure Land Buddhism. They believed in salvation for all humanity, not just those with the time and inclination to study the details of religion. They were, therefore, more egalitarian than the sohei; being a mass social movement under arms rather than a cadre of elite fighters.

Some Ikko-Ikki shaved their heads as a sign of their faith. Aside from that, they looked and fought much like the samurai-led armies they opposed. They gained enough power to take control of the province of Kaga in 1488, before being driven back as a fractured Japan was reunited over the next century.

We know less about the Ikko-Ikki than about many other warriors of the time. They have left an impression of being something akin to Europe’s peasant revolts, but with an added tone of religious fanaticism that made them tough opponents.

Ronin

To be a samurai was not just to be a warrior. It was to be part of a clear hierarchy, to know your place and to defend it.

Sometimes a samurai lost his place in the hierarchy. It could happen when his daimyo, or lord, died or was disgraced, leaving him without a master. He then became a ronin, a word meaning “man of the waves.”

Without lands of their own or regular income, penniless ronin sought employment the best way they knew – by hiring themselves out as mercenaries. During the violent upheavals of the late 15th and 16th centuries, such work was plentiful. As order in Japan was restored, there was less and less work for such men.

Ninja

Japan’s secretive assassins, the ninjas, left even less information about their activities than the Ikko-Ikki. Ninja lore is full of rumor, uncertainty, and exaggeration.

The ninjas played a very different role from the other warrior groups. They did not fight on the battlefield. Instead, they fought from the shadows, using stealth and cunning to assassinate enemies. The daimyo Uesugi Kenshin, who died in 1578, was rumored to have been killed by a ninja who spent days hiding in the filth of a lavatory. He was waiting for his chance to strike at his victim’s most vulnerable and unsuspecting moment.

Ninjas dressed in all-encompassing outfits to conceal them from view. They were black for night work and khaki brown for daytime.

Ashigaru

Like European knights, the samurai were symbolic of the wars they took part in due to their glamor and status; not because they were the most common participants. The bulk of feudal Japanese armies were made up of ashigaru, the ordinary foot soldiers.

The equipment of ashigaru varied considerably. Many wore the okegawa-do, the simplest form of battle armor. It consisted of two parts, one protecting the front and the other the back, connected by a hinge and cord.

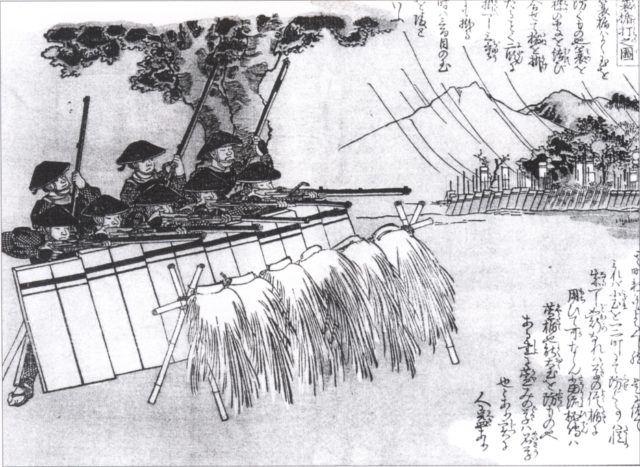

The ashigaru fought with spears, swords, and bows. In the 16th century, gunpowder weapons were coming to the fore. The warlord Nobunaga won a great victory in 1575 by equipping 3,000 of his ashigaru with arquebuses.

Tsukai-ban

To be effective, any army needs communications. Every daimyo of note kept a tsukai-ban, a messenger corps. Those soldiers ensured the coordination and transmission of information between units on busy and chaotic battlefields.

Source:

Stephen Turnbull (1987), Samurai Warriors