In 2002, Nicholas Cage starred in Windtalkers as a soldier assigned to protect a Navajo soldier who used his native language as an unbreakable code.

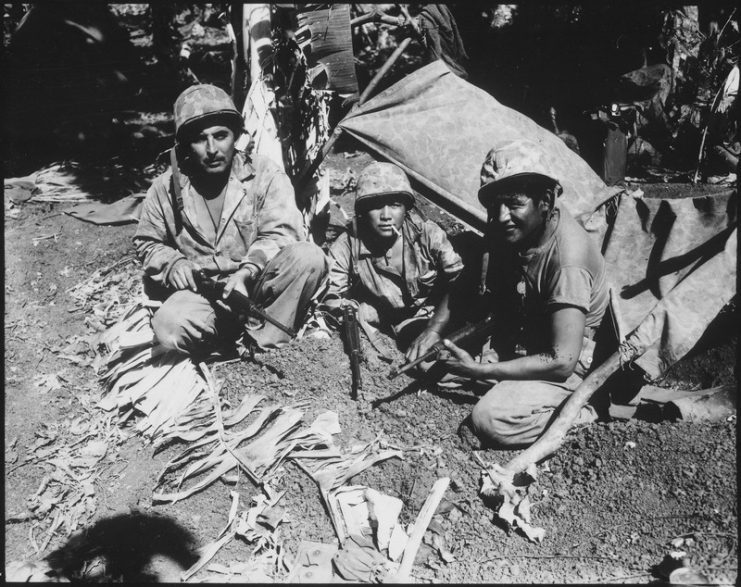

The Navajos spoke to each other in their own language, which was one that the Axis powers in WWII could not comprehend or translate.

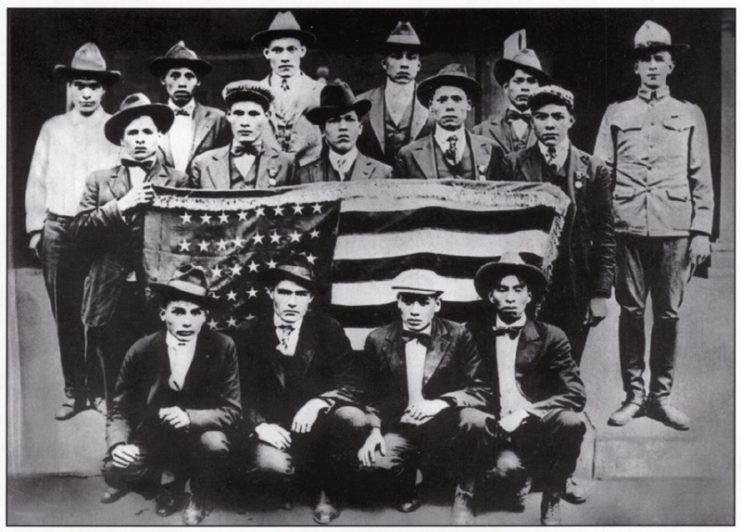

The history of the code talkers stretched back to World War I when the US military employed Choctaw Indians using their mother tongue to “encode” military orders and other communication when speaking on open telephone lines.

Twenty years later, the US Army recruited Choctaw, Hopi, Cherokee, Comanche, and Mohawk people for their communication encoding program. The Marine Corps recruited Navajos from the American Southwest.

At the height of the program, there were more than 400 Navajo native speakers serving with the Marines.

Learning from their experience in WWII, the Germans and their Axis partners, including the Japanese, began studying the languages of the American First Peoples to thwart the code talker programs.

However, the Marines’ choice in recruiting the Navajo people was inspired, as the Navajo language is incredibly difficult for a foreigner to learn.

In addition, the speed at which the Navajo people spoke made the messages they were exchanging far more secure and also meant they could be encrypted much faster than they would be using the technology available at the time.

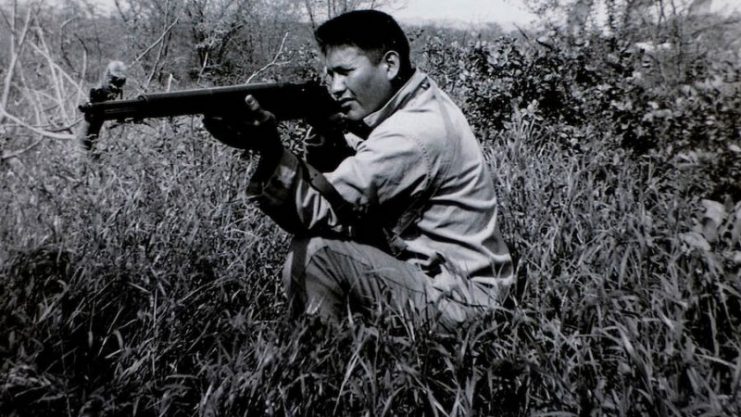

The Marine Navajo code came in two types. The first, known as Type One, used Navajo words representing each letter in the English alphabet, in a manner like the current NATO Phonetic Alphabet. The Navajo words would then be used to spell out the words in the message.

Type Two Code was used when the entire message was translated from English into the Navajo language and transmitted like that. The code talkers also used words made up especially for them to denote military terms that would not typically be found in their language.

The code talkers were sworn to secrecy, and it was not until 1968, over 30 years later, that the US Government lifted the shroud of secrecy around this program.

Even after that, the program remained mostly unknown until Nicholas Cage and Hollywood shone a spotlight on the program and the vital part these men played during the war.

The men themselves never spoke of what they did during the war. Raymond Oakes, whose father was Levi Oakes, a Mohawk code talker during the war, was absolutely astounded to hear an Akwesasne radio program that told the story of his father’s contribution to the war.

When he asked his 93-year-old father about it, his father told him that he was not allowed to talk about it.

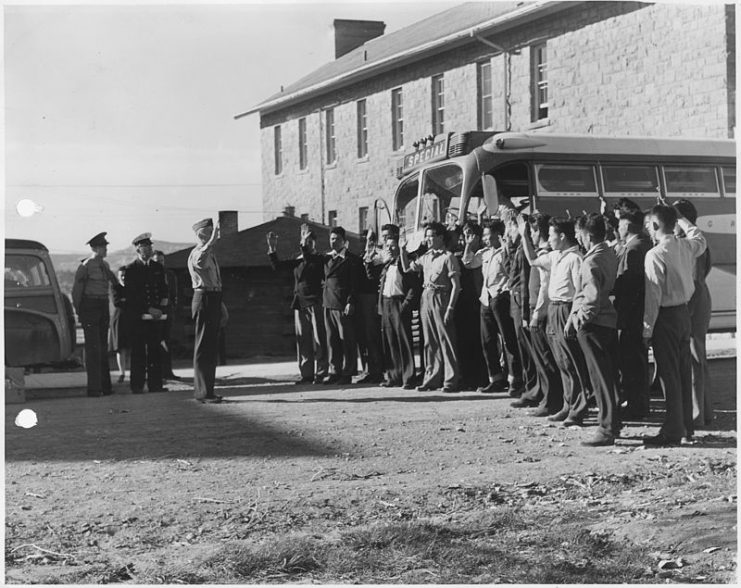

Raymond then found that Levi, who was born in Akwesasne, joined the US Army when he was 18. He went with another 17 code talkers from Akwesasne to serve in the South Pacific, Philippines, and New Guinea.

Altogether the code talkers in his group spoke 33 tribal languages and used all of them for communications.

Levi was discharged honorably in 1946. He worked as an ironworker in Buffalo and for the highway department in New York.

While serving with the US Military, Levi was awarded the American Silver Star for courageous conduct and in 2016 he, along with all the other code talkers, received the Congressional Silver Medal.

Levi Oaks was honored for his service at a Special Chiefs Assembly at the Assembly of First Nations, in Ottawa, Canada. He was also recognized by members of parliament from the House of Commons in Ottawa.

Levi Oakes is a living legend and a hero, but he is a little scornful of the war films that are produced in Hollywood.

When hearing the famous line uttered by John Wayne, that the soldiers must not shoot until they see the whites of the enemy’s eyes, Levi has a quiet chuckle. He quips that when he was serving, all it took was the snapping of a twig for everyone to open fire.

He is also sad about how his language has been treated throughout the years.

As a very young child, he spoke his mother tongue but when he started school, the teachers did not allow them to use their own language. The children were beaten if they spoke in it.

When he was in his late teens, suddenly his home language was once again relevant, but when the war was over, it was once again taken from him.

Read another story from us: Marines’ Secret Weapon in the Pacific: Navajo Code Talkers

This proud First Nation man has seen prejudice against the language of his people for most of his life except when it was valuable to the military.

It is a sad reflection of the culture that we live in that everyone, especially his fellow citizens, can not appreciate the beauty of his mother tongue.