A good portion of the fighting that occurred between the Axis and Allied powers during World War II took place in the sky, and pilots had to contend with not only enemy aviators, but also another tricky opponent: gremlins. These pesky creatures wreaked havoc on pilots and flight crews alike, making an already difficult task that much more dangerous.

What is a gremlin?

For the majority of the population, the word “gremlin” brings to mind the 1984 cult classic film by Joe Dante. However, for those in the military – in particular, the Royal Air Force (RAF) – it conjures up another image, one of a menacing creature lurking in the shadows of an aircraft, waiting to cause trouble.

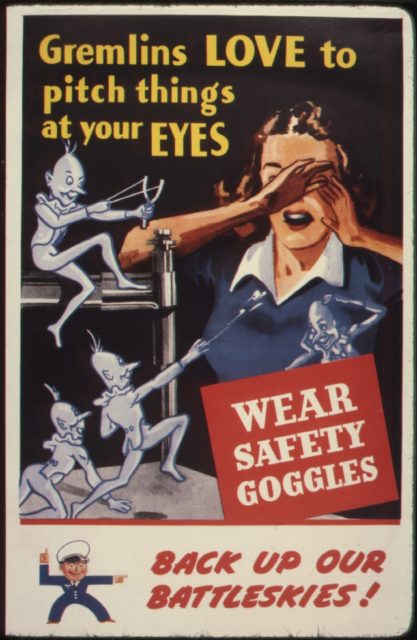

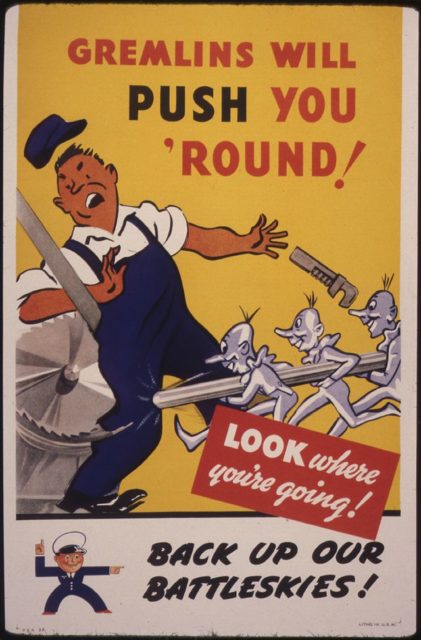

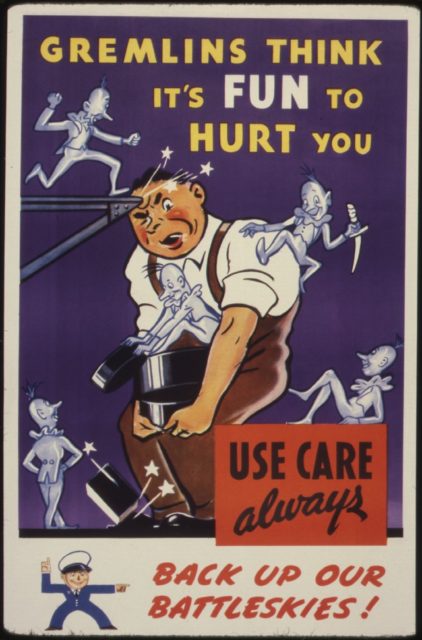

Depictions of gremlins vary, as different types were described by service members. In general, they were said to have large eyes, sharp teeth and claws, and spiky backs. They looked rather cartoonish, standing at one foot tall and having brightly-colored skin in shades of blue, green and brown.

Many variations caused different types of trouble. The “Jockey” sat cross-legged on birds and guided them into the windshield of fighter aircraft, while “Optics” hid in bombsights to throw off a bomber’s vision when aiming at a target.

“Bombii” gremlins caused bombs to change direction and land away from their targets, and “Water” ones disabled carburetors by leaking water into fuel lines. When not fooling around with aviators, they messed around with flight crews, hiding compasses and disrupting radio frequencies.

Fabled origins

The origin of gremlins is disputed. Some derive it from the Old English word Gremian, or “to vex,” while author Carole Rose, in her 1996 book, Spirits, Fairies, Leprechauns, and Goblins: An Encyclopedia, attributes their creation to the blending of Brothers Grimm and Fremlin Beer.

The majority attribute the creatures to the Royal Air Force, however the exact date is debated. Some believe they date back to the First World War, despite there being no written evidence, while others say it was slang used by pilots stationed in Malta, the Middle East and India during the 1920s. This is where the earliest recorded print evidence is seen, in a poem written on April 10, 1929.

Another early reference is included in aviator Pauline Gower‘s 1938 novel, The ATA: Women With Wings, where she describes Scotland as “gremlin country,” known to house scissor-wielding gremlins that cut the wires of biplanes.

The term “gremlins” was most widely used during World War II, with the first, as shown in an article published in the Royal Air Force Journal on April 18, 1942. Pilot Hubert Griffith chronicled the creatures, noting they largely made an appearance during the Battle of Britain in 1940. He believed they weren’t always malevolent and had a rather playful sense of humor.

Spread of gremlins during World War II

As aforementioned, gremlins during World War II are most associated with the Royal Air Force units – in particular, high-altitude Photographic Reconnaissance Units (PRU) based out of of RAF Benson, St Eval and Wick. Their aircrews blamed the tricksters on otherwise inexplicable accidents, and they eventually became a scapegoat for issues that occurred when flying.

They were once thought to be sympathetic toward the enemy, but this was later deemed false, as enemy aircraft suffered similar issues. As such, gremlins were portrayed as tricksters of opportunity, acting on self-interest.

Gremlins soon spread to the US Air Force, whose pilots began to complain about a host of issues, including reliable engines failing and nuts coming loose. While most American airmen looked upon them as negative, others viewed them in a different light, such as the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), who adopted the gremlin Fifinella as their official mascot.

By the end of the Second World War, gremlins had become solidified in Western flying lore. This was helped by Roald Dahl and the Walt Disney Company. The famed children’s author, who was an RAF fighter pilot, was commissioned to write a book about them, titled The Gremlins. This led to their further spread in popular culture. Soon, they were featured on such television shows as The Twilight Zone (1959-64) and the Looney Tunes.

Deflecting blame and boosting morale

For many during World War II, gremlins were a way to deflect blame. Much of what they were accused of could be attributed to human or machine error. Rather than place the blame any one person, it was easier to blame a fictional creature. According to historian Marlin Bressi, this helped keep morale up among Royal Air Force pilots:

“Gremlins, while imaginary, played a very important role to the airmen of the Royal Air Force. Gremlin tales helped build morale among pilots, which, in turn, helped them repel the Luftwaffe invasion during the Battle of Britain during the summer of 1940. The war may have had a very different outcome if the R.A.F. pilots had lost their morale and allowed Germany’s plans for Operation Sea Lion (the planned invasion of the U.K.) to develop. In a way, it could be argued that gremlins, troublesome as they were, ultimately helped the Allies win the war.

“Morale among the R.A.F. pilots would have suffered if they pointed the finger of blame at each other. It was far better to make the scapegoat a fantastic and comical creature than another member of your own squadron.”

More from us: Was the Allied Bombing of Dresden a War Crime or Wartime Necessity?

Critics believe the stress of combat and the high altitudes at which pilots flew led to hallucinations. As such, the existence of gremlins became a sort of coping mechanism. Regardless of how one looks at it, the existence (or not) of these creatures is a lighter topic in an otherwise devastating conflict.