The Second World War was a period of greatly accelerated development in the field of aviation: this was the first war in which jet fighters were used, and bigger bombers than the world had ever seen rained down death from the skies.

It is tempting to think that these types of airplane – the biggest, fastest, most powerful, most technologically advanced models – were solely responsible for winning the air war.

However, in focusing entirely on the flashiest, most impressive planes, it’s easy to lose sight of the plainer, simpler and smaller aircraft that played an equally important role in the Allied victory. One of these models was the Fairey Swordfish, nicknamed the “Stringbag,” a basic torpedo bomber biplane used extensively by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy during WWII.

It was one of these humble planes that, reminiscent of Luke Skywalker taking out the Death Star in Star Wars, managed to disable one of the German Kriegsmarine’s most gigantic ships. Another Stringbag was also the first Allied plane to sink a German U-boat, and then later yet another of these unassuming airplanes was the first to sink a U-boat at night.

Stringbags also relentlessly harried the Axis shipping fleet in the Mediterranean, accounting for over a million tons sunk by the end of the war – not a bad tally for an outdated biplane!

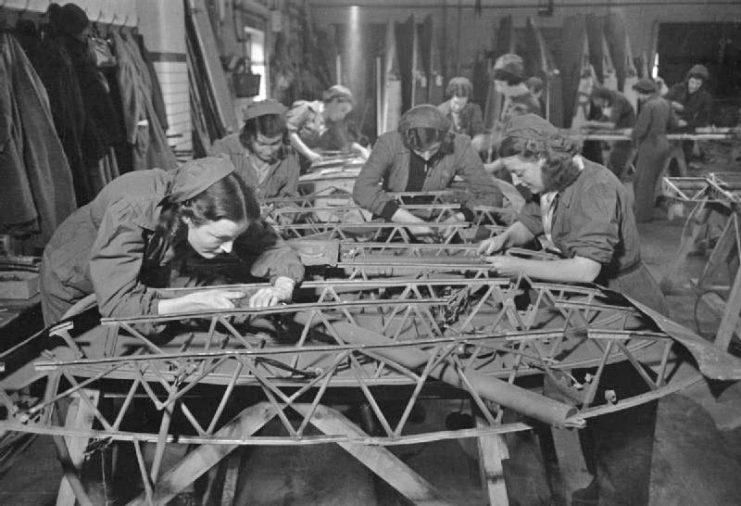

Looks and performance-wise, the Fairey Swordfish bore a much closer resemblance to the airplanes of the First World War rather than those of the Second. With its open cockpit, fixed landing gear and its pair of stacked wings, by no stretch of one’s imagination could this humble plane have been described as “cutting edge” even in 1933, when the first prototype was built.

However, despite its outdated design, it was no less important to the Allied war effort than its more technologically-advanced compatriots. Indeed, the Swordfish’s antiquated appearance was deceptive – not so much in terms of its flat-out performance, but rather in terms of the roles it was able to perform.

In addition to being armed with two basic but reliable 7.7mm machine guns, one fixed in position for the pilot in the front and one trainable at the rear for the gunner, the Swordfish was able to carry a wide variety of ordnance: anti-ship mines, depth charges, bombs, flares, or a ship-sinking 1,610-pound torpedo.

The plane was also used for a variety of roles, including reconnaissance, bombing, escort duty, or naval artillery spotting.

Because of the variety of ordnance the Swordfish could carry and the diversity of its roles, it was given the nickname “Stringbag,” likening the plane to a popular style in women’s handbags at the time. Humorous as it was, the nickname was apt and it stuck.

As a basic three-seater biplane with a simple Bristol Pegasus motor that cranked out 690-odd horsepower, the Stringbag wasn’t going to be breaking any speed records in the air. However, the simple design meant that maintenance of the aircraft was easy, and that the planes were reliable.

The twin wings meant that the Stringbag had an excellent lift and could take off or land on a relatively short strip of land. This made Stringbags perfect for use on naval aircraft carriers, with their very limited landing and takeoff space.

Stringbags were also extraordinarily maneuverable, making up for their slow speed with excellent agility. Their fabric-covered, all-metal understructures were sturdy enough to deal with harsh landings, and this meant that they were ideal for night use – an excellent advantage, when they could fly all but invisible to Axis ships or other targets below.

These planes weren’t without their disadvantages, of course. They were at a severe disadvantage when it came to air-to-air combat against Axis fighter planes, and the open cockpit meant that the men in the plane would suffer immensely in the cold. Early in the war, Stringbags didn’t have communication radios, so they had to rely on hand-held signalling devices.

Nonetheless their advantages generally outweighed their disadvantages, and Stringbags saw extensive use throughout the war. In one of the most famous incidents in which they were involved, a Stringbag was instrumental in the sinking of one of the Kriegsmarine’s mightiest ships, the battleship Bismarck.

The Bismarck was, at the time of its production, the most powerful warship ever made. In a sortie into the Atlantic aimed at crippling Britain’s crucial supply lines, the Bismarck battled and sank the British battle cruiser HMS Hood.

Realizing the Bismarck had to be stopped, Britain launched a pursuit, but the Bismarck managed to evade her pursuers. The only ship close enough to have a chance of disabling the giant was HMS Ark Royal, which had a few Stringbags equipped with torpedoes aboard. The Stringbags took off an hour before sunset on May 26, 1941 to take on the German behemoth.

As the Stringbags, each carrying a single torpedo, approached the Bismarck they dived low, hoping to evade the flak that filled the air from the ship’s anti-aircraft guns. One Stringbag, piloted by Lieutenant Commander John Moffat, got the Bismarck in its sights.

Moffat and his observer, Flight Lieutenant JD Miller, had to time the release of their torpedo with extreme precision. They only had one chance to do this, and if they missed or the torpedo hit the crest of a wave in the extremely choppy sea, it was mission over. With flak flying all around them, and Miller waiting for the exact moment, Moffat’s hands were surely sweating on those controls.

Finally, the moment came, and the torpedo was dropped. Against all odds it hit home, striking the mighty battleship in a small area of vulnerability: the rudder, which the torpedo succeeded in jamming mid-turn.

With her rudder jammed to port, and thus unable to move in anything but endless circles, the Bismarck became a sitting duck. British naval ships later surrounded the Bismarck and eventually sank her after extensive bombardment.

Stringbags also played a key role in the night attack on Italy’s Taranto naval base. Two waves of Stringbags launched a surprise attack on the naval base on the night of November 11, 1940, and succeeded in destroying or disabling the bulk of Italy’s naval fleet – an attack that would be carefully studied by the Japanese, who would use similar tactics to attack Pearl Harbor.

Stringbags also saw extensive use in taking out Axis shipping lines, especially in the Mediterranean, where they sunk over a million tons throughout the war. All in all, this humble airplane proved its worth to the British Royal Navy many times over during the course of WWII.