The 19th century saw an incredible advance in ship designs, from full-rigged wooden ships to enormous iron and steam liners. Progress was achieved through experimentation, and the Stevens family of New Jersey were leading the way.

Their involvement in nautical design dates back to the late 18th century when John Stevens began experimenting with steam engines and propellers on ships. Advancements in steam engines and ship design helped bring the family wealth.

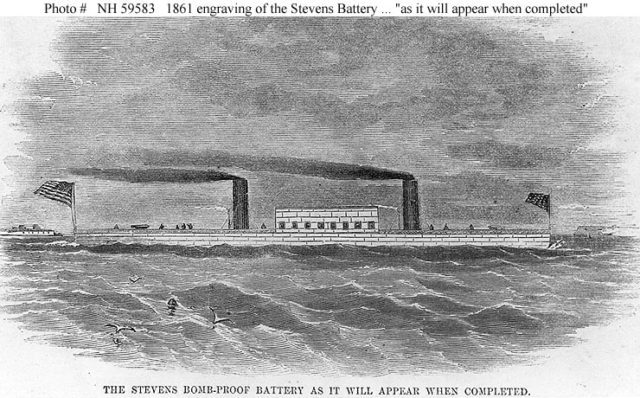

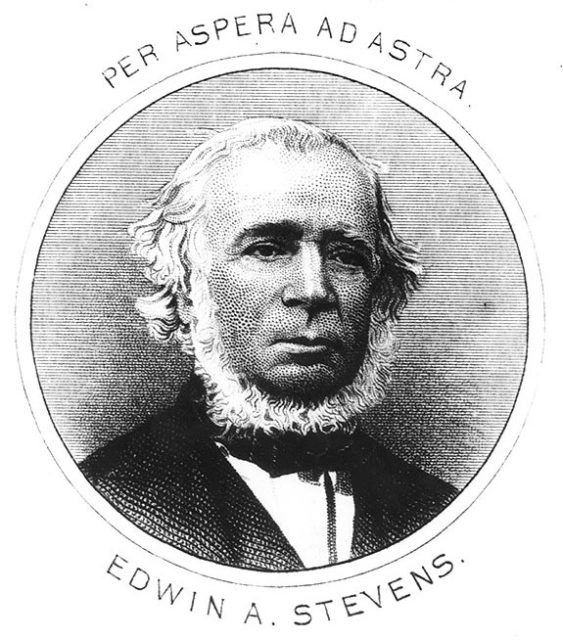

By the 1840s Edwin A. Stevens and his brother Robert L. Stevens had proposed a radical new design: the Stevens Floating Battery. It was an iron-hulled steamship, with its engines below the water line, powering a screw propeller. Above the water, it would have over 4 inches of armor, and powerful cannon.

However, persistent technical problems and high costs plagued the project; the Stevens brothers needed to test their idea further.

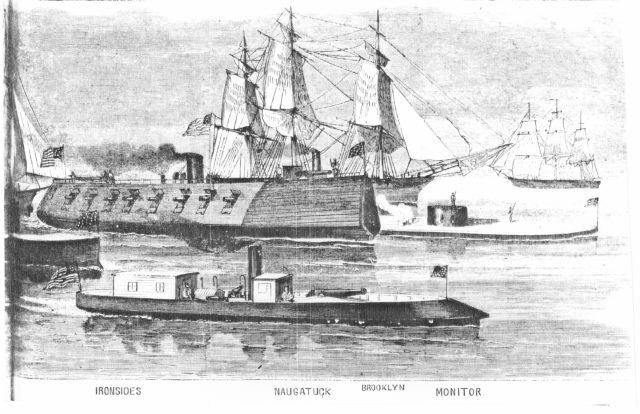

In 1860, the brothers knew that war was coming to the United States. Tensions over slavery and states rights were boiling over, and the nation was on the brink of a civil war. They purchased a small steamship, the Naugatuck. She had formerly served as a freight hauler for the Ansonia Copper and Brass Company, running from New London Connecticut to New York. Despite her somewhat humdrum background, she was about to become one of the most technologically unique ships of the American Civil War.

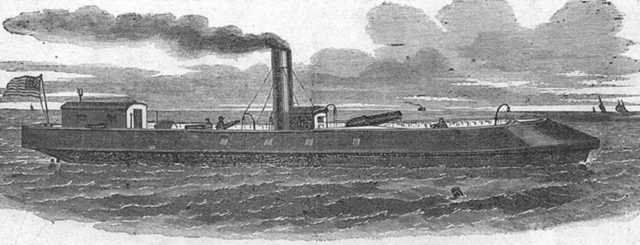

The Stevens brothers originally intended the floating battery to be used as a harbor defense weapon. They rightfully predicted it would be incredibly useful for a Navy to use in blockading a river or harbor. The vessel also had to operate in shallow waters, requiring the use of pumpable ballast tanks. In doing so, they could alter the draft (how much of the vessel sits below the water) at will. Shortly after purchasing the Naugatuck, the two brothers set about modifying her as a test bed for their designs.

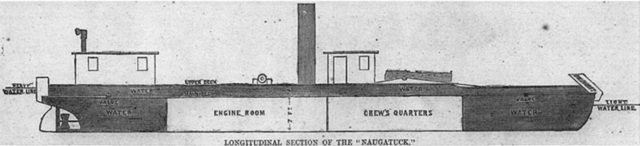

They installed two large ballast tanks, one forward and one aft, with engine and crew compartments amidships. With the addition of two centrifugal pumps, they could raise and lower the ship in only nine minutes, a surprising speed for the age.

She could also pump out her tanks to increase speed, going from a lumbering 5 knots to a not quite record breaking 10 (other European ironclad ships were regularly reaching 12-14 knot speeds under steam). 10 knots was hardly an incredible speed but it outpaced most other ships of her class such as the French floating batteries used at the Battle of Kinburn in 1855, or the Monitor and City class ironclad gunboats of the later years of the American Civil War.

Above deck, she had an armored bulwark made of thick cedar planking behind iron sheathing. It provided an early type of composite armor which, was hoped, would protect the crew against most enemy fire. The best protection was offered by the ship’s low profile, especially when the ballast tanks were filled. It allowed only her wheelhouse, officers cabin, and smokestack to be targets above dec. The cabin and wheelhouse were armored as well.

For armament, she had two 12 pounder Dahlgren Howitzers mounted on pivots, just aft of the wheelhouse, on either side of the boat. Located just over the crew compartment, her main gun was a real innovation for the period. She had a 100 pounder Parrott Rifle; a large, and accurate, naval artillery cannon. It was the first one ever produced, and the design became standard on many fighting ships, on both sides of the war.

What was more important, though, was the cannon’s mounting. It was fixed in line with the ship, on a swinging mount which enabled the gun’s recoil to propel the weapon below deck after every shot. The Parrott was muzzleloading, and the ability to keep the entire crew below deck could potentially take them out of the line of fire completely. The system was able to fire every 25 seconds, a high rate for the time.

In 1862, the brothers tried to donate the vessel, which had been renamed E.A. Stevens to the Union Navy. The Naval Board rejected it, saying it was untried, and due to its many technological innovations, there was too much which could go wrong in combat. They were undaunted, and brought their ship, instead, to the US Revenue Cutter Service, a predecessor of the US Coast Guard.

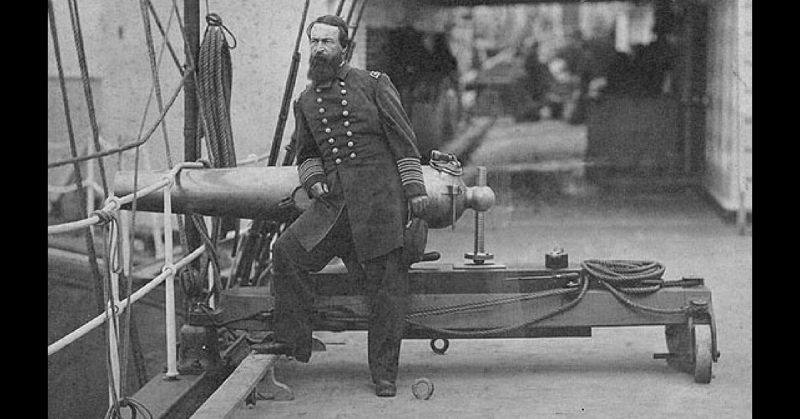

Given a crew of 24, and put under the command of Lieutenant David Constable, USRCS, she was assigned to the North Atlantic Blockade in March 1862. There she engaged in a brief fight with the CSS Virginia before the Confederate ship was beached and burned after the CSA’s ground troops left Norfolk.

Her weapons proved worthy, as did her ability to lower her profile to protect her crew. The theory was confirmed, and she would soon see combat again.

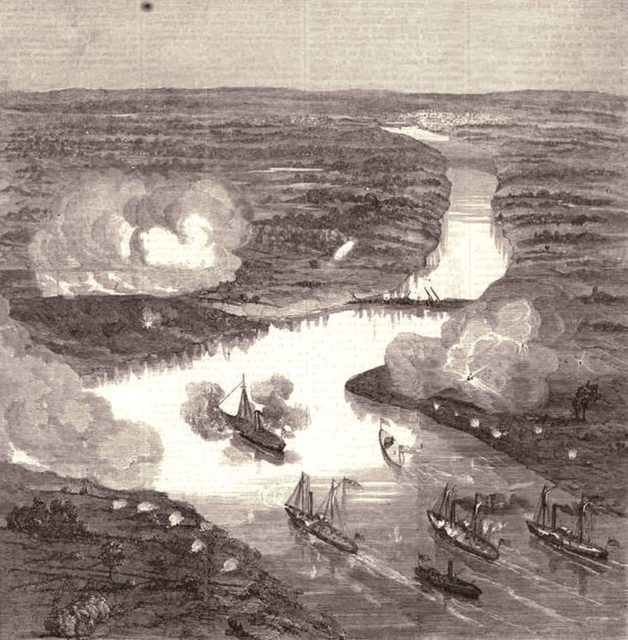

On May 15, the Stevens steamed up the James River, as part of a fleet led by the USS Galena consisting of three traditional ironclads, as well as the USS Monitor. They reached Fort Darling and came under fire from the eight heavy artillery pieces positioned there.

The ironclads were too big and easy a target for the Fort batteries, so the USS Monitor moved forward. She was designed for ship to ship combat, not shore bombardment and her cannons could not reach the correct elevation. The Stevens moved up to take her place.

The Revenue Cutter fought admirably, her advanced weapon systems functioning almost perfectly. Being so low in the water, she proved a difficult target for the Fort, and her armored deck and bulwarks provided sufficient cover for her crew while they loaded and fired her main gun. However, catastrophe struck!

The Parrot rifle burst while firing. It was the first ever manufactured and had undergone substantial testing before being used in combat. It had weakened the gun, leading to the break. The Stevens was forced to retreat. Her main gun carriage design was well ahead of its time. While disappearing mounts saw only limited use on Naval ships, they became very popular for shore batteries by the end of the 19th century.

The E.A. Stevens continued serving with the Revenue Cutter Service until 1889 when she was sold. The innovative and unusual design had proven a variety of useful theories in ship design. Her place in history is overlooked, but the use of fast pumping ballasts, twin screw propellers, gun recoil systems, and hidden loading systems helped push naval technology forward.

It was a shame an exploding cannon spoilt her record. Had it not been for the Parrot gun’s failure, it is possible the US Navy would have adopted recoil and loading systems much sooner.