Soldiers win wars. Officers might make the calls, set the strategy, and direct the action, but when it comes down to the actual hard sacrifices, it’s always the common soldier that wins the war.

This dictum appears both simple and obvious: if a country elects to send soldiers into hostile, foreign territory with the aim of engaging in a long, protracted conflict, then they had best ensure that they’re up to the task. Otherwise, the engagement will be a waste of time, resources, and manpower.

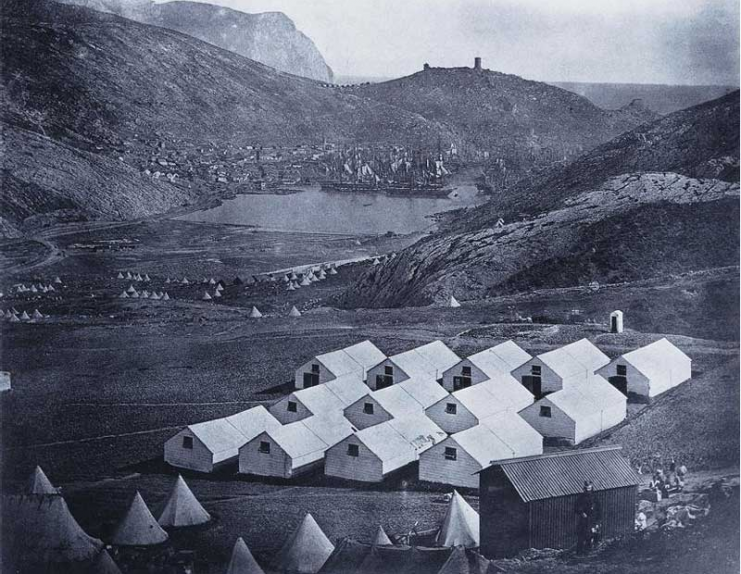

Yet one of the most successful military forces of the nineteenth century, the British empire, apparently forgot this simple dictum when it came to fighting in the Crimean War (1853-1856). This resulted in failures that were so abominable and thoroughly avoidable that they became a national scandal.

The empire was a bureaucratic mess. Food supplies were poor. Half rations were the norm, and it wasn’t at all uncommon for men to not eat at all, such as what happened on Christmas Day of 1854, when Colonel Bell’s troops went hungry.

When there was food, it wasn’t any good. The average soldier’s diet consisted of biscuits and salt meat. Some men couldn’t eat the meat, complaining of the horrid diarrhea that resulted. Even when fresh meat was available, the salt meat sometimes would still be given out instead because it was less of a hassle.

The biscuits were hard and difficult to bite through, causing even more pain to gums already inflamed with scurvy. A month’s worth of vegetables was two potatoes and an onion.

The British had bakers among their troops, but didn’t see the value in letting them ply their trade. They could have taken a lesson from the French in that regard. For contrast, the diet of British soldiers fighting in the Crimean War was actually worse than that of the Scottish prisoners back home in British jails, who were fed rations of milk, vegetables and fish.

The situation was only made worse by the class-based institutional arrogance and bureaucratic incompetence of supply officers. In November 1854, one hundred and fifty tons of vegetables arrived at Balaclava without the correct documentation. Because the cargo lacked documentation, no one in Balaclava would accept responsibility for it, so the food was wasted.

In an attempt to ease the troops’ suffering, Lord Raglan ordered that each man would receive two ounces of rice a day. Later, someone failed to renew the order, stopping the rations. The Commissariat still had rice at Balaclava and Scutari, but had no way to get it to the front, and so the soldiers starved.

To combat the scourge of scurvy, the British navy had long since used lime juice, which provided the vitamin C necessary to avoid the disease. The soldiers in the Crimea came down with scurvy as there was a distinct lack of vitamin C in their diet, so the British sent nearly 20,000 pounds of lime juice to solve the problem.

Inexplicably, Commissary-General Filder ignored the newly arrived cargo, stating that it was somehow not his job to inform the troops of its presence. Therefore his men were ravaged by scurvy for two months, all while they were unaware that the antidote to their problems was available.

A similar problem happened with coffee. In an attempt to avoid the damp and mold that comes with shipping coffee beans, Filder ordered that the beans should be sent unroasted to the Crimean troops.

However, the troops had no way of efficiently grinding or roasting them. The men were forced to either improvise by grinding them in shell cases and roasting them alongside their meat, or to drink a foul brew of half-rotten green coffee beans. To make this matter worse, 2,075 pounds of tea sat untouched in Balaclava.

The food problems are only one example of the trials and tribulations of the average British soldier fighting in the Crimean War. Footwear and uniforms were another whole story of misery.

In the end, an investigative commission discovered that a large number of wartime deaths were attributed not to the guns of the enemy, but to supply failures and the greater problems of leadership in the British empire.