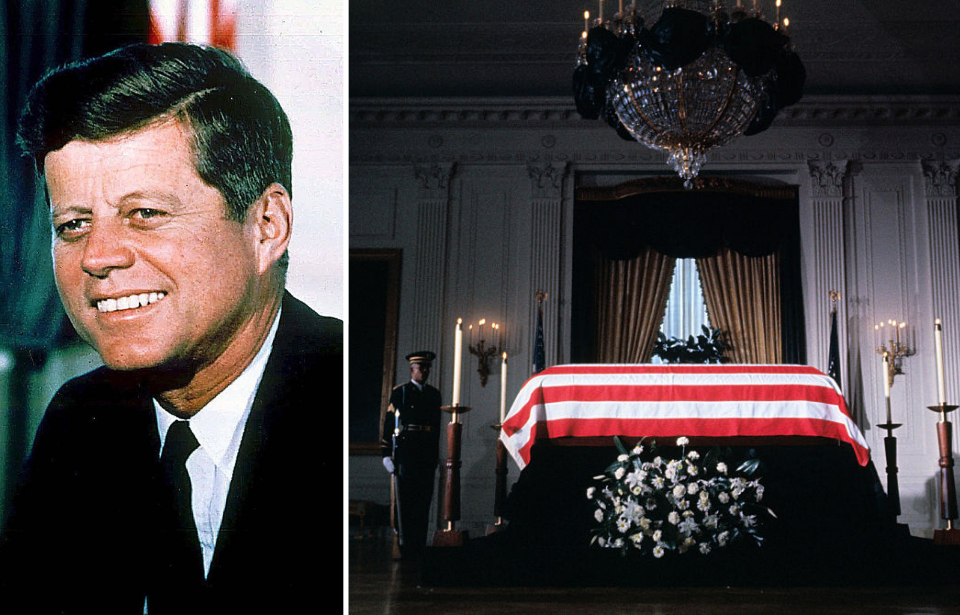

John F. Kennedy’s assassination

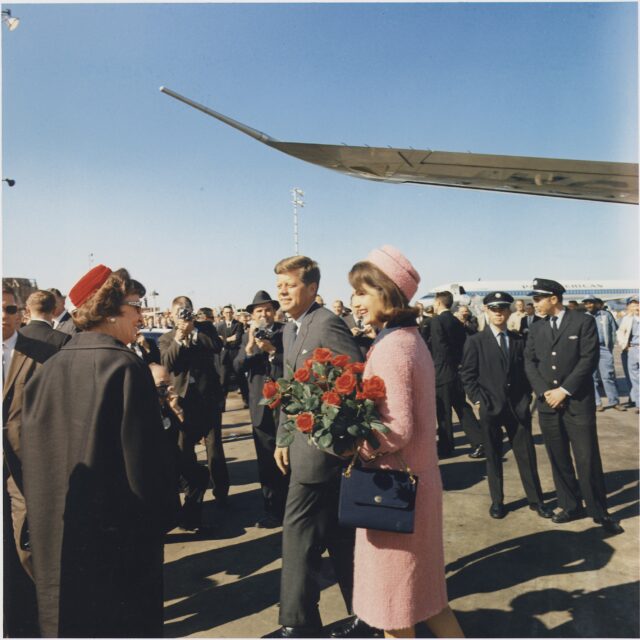

On November 22, 1963, John F. Kennedy, accompanied by Texas Governor John Connally and their spouses, was traveling in a motorcade through downtown Dallas. At 12:30PM, gunfire erupted from the Texas School Book Depository, targeting the procession. The assailant responsible for the shooting was identified as US Marine Corps veteran Lee Harvey Oswald, who’d recently gotten a job at the book depository.

Kennedy sustained injuries to his head and neck, and Connally was struck in the back. Kennedy was promptly taken to Parkland Memorial Hospital, where he was declared deceased at 1:00 PM. Despite sustaining serious wounds, Connally eventually recuperated from his injuries.

Shortly before 2:40 PM, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had been traveling with the Kennedys in the motorcade and was positioned two cars behind during the incident, was inaugurated as the 36th president of the United States aboard Air Force One.

The need for two coffins

Immediately after President Kennedy was shot, a staff member contacted O’Neal’s Funeral Home in Dallas, urgently requesting their finest casket for rapid transport to the hospital. Funeral director Vernon O’Neal selected a high-end bronze casket with a white satin interior from the Elgin Casket Company. At $3,995 in 1963, the cost would be roughly equivalent to $36,000 today.

O’Neal personally delivered the coffin by hearse, unprepared for the severity of Kennedy’s injuries. With blood still oozing from the fatal wounds, he and several attending nurses quickly wrapped the president in linen and lined the casket with plastic to contain the bleeding and protect its interior.

The casket was not useable for the viewing

At Jacqueline Kennedy’s request, the autopsy was done at Bethesda Naval Hospital, just outside Washington, D.C. Her husband’s body was placed in the passenger area of Air Force One and flown back to the capital. When doctors opened the casket at the hospital, they discovered that the preservation efforts by O’Neal had not been very effective.

After the embalming process, the original casket was no longer suitable for Kennedy’s public viewing at the Capitol and had to be replaced. Unsure of what to do with the first casket, the funeral home that handled the embalming ended up keeping it for over a year.

Preventing it from falling into the hands of the “morbidly curious”

After Kennedy was buried, a dispute arose between the US government and Vernon O’Neal regarding the cost of the original coffin. The government considered the price to be exorbitant, while O’Neal sought its return to Dallas, having received offers of $100,000—almost $1 million in today’s money—from interested buyers.

Not wanting the casket to fall into the possession of the “morbidly curious,” the government settled its debt with O’Neal and stored it in the National Archives, where it stayed for two years.

Burying the casket at sea

In 1999, records were released concerning the final fate of the casket after its time in the National Archives. Robert Kennedy, who served as the United States Attorney General at that time, had petitioned the government to ensure it was buried at sea, preventing it from falling into the wrong hands of people seeking to exploit his brother’s death. After receiving approval, the responsibility for its disposal was entrusted to the US military.

A submarine commander was assigned the task of coming up with a secure method to drop and sink the casket. It was then handed over to the US Air Force, where it underwent the process of having 42 holes drilled into it and being loaded with three 80-pound sandbags. Additionally, two parachutes were installed to prevent it from breaking apart upon impact with the water.

A transport plane took it out to the Atlantic Ocean

In February 1966, on a cold morning, a C-130 Hercules transport plane lifted off from its base and headed out over the Atlantic, about 100 miles east of Washington, D.C. Its destination was a remote military dumping ground for outdated weapons and ammunition. The site had been carefully chosen for its seclusion, far from busy air corridors and shipping lanes, ensuring the materials would “not be disturbed by trawling and other sea-bottom activities.”

Flying low at just 500 feet, the C-130 opened its rear hatch and released the coffin into the Atlantic. According to a memo from the defense secretary’s special assistant, dated February 25, 1966, parachutes opened moments before the casket touched the surface, allowing it to stay intact as it sank quickly and smoothly after a quiet splash. The aircraft then circled the drop zone for ten minutes before heading back to base.

The decision to commit the coffin to the sea carried symbolic weight—it honored Kennedy’s service as a Navy officer and echoed his own reflections on the idea of a seaborne burial.