She was a British aviator in the 1930s who showed what women could do by setting several impressive records.

Amy Johnson was born on July 1, 1903, in Yorkshire, England. She graduated from Sheffield University with a Bachelor of Arts in Economics, following which she worked as a secretary. However, it was not her thing.

Aviation was. By June 1929 Johnson had earned an aviator’s certificate, and by July 1929 she qualified as a pilot with the London Aeroplane Club. Determined not to be just a pretty face who could fly, she went on to become the first British woman to earn a ground engineer’s “C” license.

Flying and fixing planes was one thing, actually owning one was another. Fortunately, her parents were very supportive, and her father had very modern ideas about women. With his help, together with Sir Charles Wakefield (the Lord Mayor of London), she bought one.

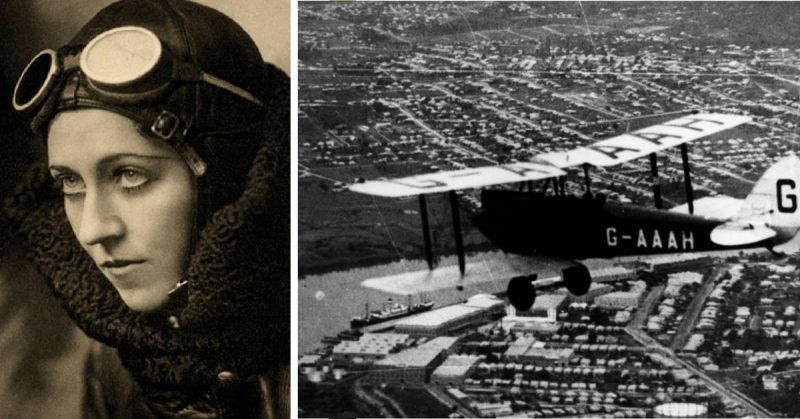

It was a de Haviland DH 60 Gipsy Moth G-AAAH 1920s two-seater touring and training plane. It was second-hand but she knew how to maintain it. Johnson named it Jason after her father’s business trademark. She then made headlines in 1930.

On May 5, Johnson took off from Croydon, London and flew 11,000 miles to Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia. She reached there on May 24 – making her the first woman to fly that route solo. Johnson earned the Harmon Trophy and an Order of the British Empire (CBE) medal.

The Australians also awarded her with a No. 1 civil pilot’s license. Armed with that, she bought herself a Havilland DH 80 Puss Moth G-AAZV three-seater monoplane which she named Jason II. In July 1931, she and her co-pilot – soccer player Jack Humphreys – became the first to fly to Moscow (1,760 miles away) in 21 hours.

Next, they flew off over Siberia and landed in Tokyo, Japan – setting yet another record. The following year, Johnson was on a plane for the first time with Jim Mollison, a Scottish pilot, who distracted her eight hours into their flight by proposing to her. She accepted immediately, and they got married later that year.

Mollison had a reputation for breaking other pilot’s records, so what happened next was interesting. In July 1932, just months after their honeymoon, Johnson flew solo from London to Cape Town, South Africa on a Puss Moth G-ACAB named Desert Cloud. She set a new world record – beating her husband.

It set the trend for their marriage, pretty much, and the press called them The Flying Sweethearts. They tried breaking the flight record from Wales to Brooklyn, New York in July 1933 but were both injured when the plane ran out of fuel and they crashed in Connecticut. After recuperating, the couple was honored in New York City with a ticker-tape parade.

Always competing for the same records, their marriage became strained, and Mollison took more and more to drink. In May 1936, Johnson flew solo to South Africa, setting a new record in a Percival Gull single-engine monoplane. In 1938, they divorced and Johnson resumed her maiden name.

When WWII broke out, she wasted no time joining the newly formed Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) based at the White Waltham Airfield in Berkshire, England. It was a civilian organization that repaired Royal Air Force planes and flew them to wherever they were needed around Britain.

The ATA also delivered personnel, mail, and equipment, and operated an air ambulance service. A number were women as male pilots were primarily stationed overseas. From 1943, the women received the same pay as their male counterparts – a first in British history.

Johnson became a First Officer. There might have been more promotions but unfortunately, she died.

On January 5, 1941, the 37-year-old went on her last flight. It was snowing, and there was a freezing fog. The Airspeed Oxford plane she was to deliver from Blackpool to Oxfordshire had a broken compass, and the ATA wanted her grounded. She refused. Johnson had gone through far worse, she claimed, and the war was not going to be won through caution.

She took off and should have reached Oxfordshire in 90 minutes, but did not arrive. Four hours later, with her plane out of fuel, she bailed out off the coast of Kent near Herne Bay. Some people believe she was accidentally shot down while others suggest she was on a secret mission.

Whatever the case, a Royal Navy ship, the HMS Haslemere, was in the Thames River estuary and saw her parachute descend. They located her in the water but failed in their rescue attempt.

Her body was never found – leading to even more conspiracy theories about her mission and the cause of her crash.

In 2016 a historian claimed a crew member, Harry Gould, told his son he was on the HMS Haslemere that day, and according to his account, there was no mystery. The ship was a converted ferry, and the crew was trying to reach Johnson but the Haslemere hit a sandbank and became stuck.

They had to reverse off the sandbank although there were fears they might run over Johnson. Lieutenant Commander Walter Fletcher, the ship’s captain, tied a rope around his waist and dived in but could not find her. He died shortly after of hypothermia.

Gould believes that Johnson got sucked into the propeller and was chopped to pieces. Historian Dr. Alec Gill supports that idea and suggests the Royal Navy covered up her death to avoid the embarrassment of killing a national hero – especially at a time when Britain desperately needed them.