The ability to move at speed around the battlefield can create huge advantages. Before the internal combustion engine, this was usually undertaken by horses. At first, this was not achieved by the apparently simple means of riding on horseback. Instead, it was the chariot that carried warriors at the speed of a horse.

War Wagons

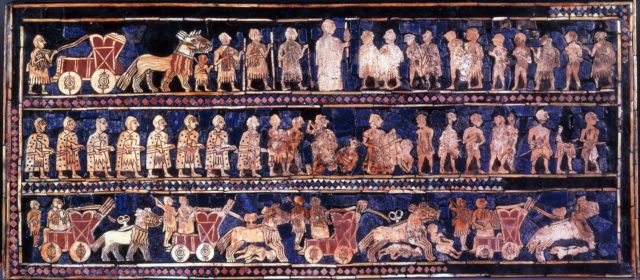

The first form of the chariot was developed in Sumer and Akkad. Horses had not yet been tamed, so it was pulled by a pair of donkeys. This allowed the occupants to move faster than men on foot, especially when those men were formed up in phalanxes of spear-wielding infantry.

The Mesopotamian war cart had high sides, with the front protection raised almost as far as the occupants’ heads. It established what would become the standard chariot team, with one man driving while the other used a missile weapon – in this case flinging javelins over the protective barrier. These spears hung in a quiver attached to the war cart’s side.

With four solid, disk wheels on two axles, this was a cumbersome vehicle. It could not turn quickly or achieve the maneuverability of later chariots. Later versions went down to two wheels, still slow and awkward but the fastest and most maneuverable weapon in the wars between Mesopotamian city-states.

Steppe Nomads And Horses

The next stage in the development of the chariot came from the Caucasus. There, steppe nomads had domesticated horses. The animals had not yet been bred robust enough to carry a grown adult on their backs, but they could be used to pull carts.

The inspiration for steppe chariots probably came from the Mesopotamian war carts. From this concept, the steppe nomads created something more specialized. Spoked wheels were used instead of solid ones. Low wicker-work sides offered less protection but added far less bulk. Strips of leather crisscrossed each other to make a strong, thin floor. All of these changes helped to make the chariot lighter and so faster.

The same steppe nomads had developed the composite bow, made out of wood, horn, and sinew. Short and powerful, this was the ideal weapon for a chariot warrior. Again, chariots had two-man teams, one driving, and one shooting. Now they could move faster, fire further, and remain out of the reach of enemy troops.

Egypt and Armageddon

Both these pieces of technology – the composite bow and the chariot – reached Egypt with the invasion of the Hyksos around 1750 BC.

Little is known about the Hyksos. They are believed to have come from the Arabian desert, chariot warfare having spread this far through wars and human migrations. The Hyksos invaded Egypt, overwhelmed the locals with their superior military technology, and occupied Lower Egypt. A century later, the Egyptians had learned this technology for themselves and used it to drive the Hyksos out.

Now came the era of Egyptian greatness. Charioteers became the most expensive, prestigious, and influential part of the army as the Egyptians carved out an empire. On their chariots, the driver carried a light shield on his left arm, providing protection for both him and the archer.

This was chariot warfare at its finest. Archers learned to volley on command, the impact of a rain of arrows far outweighing the sum of its parts. Even when they did not win, as against the Hittites at the Battle of Meggido (c. 1485 BC), their chariots were the most dangerous part of their army. Such was the destruction at Meggido or Armaggedon as it is called in Hebrew, that it became legendary as the most bloodthirsty of battles.

Assyrian Charioteers

The Assyrians made great use of chariots as their empire expanded across the Middle East from the 14th to 8th centuries BC. As with the Egyptians, their charioteers were shock troops, making them the greatest strength of their army.

Chariots featured in the region from the 13th century BC, but as late as the 9th century these were still clumsy vulnerable vehicles. It was with improvements in ironwork that the Assyrians were able to build chariots with a light undercarriage and an axle at the rear, turning them into a prime weapon of war.

Over time, the Assyrians added tougher wheels to their chariots, with more spokes and studded metal rims. They usually carried a two-man team, but after the 9th century, this started to change. Larger, sturdier chariots took multiple shield-bearers, while an archer or lancer gave the chariot its hitting power.

Providing shock assaults in the center of the battle or flanking maneuvers on the wings, chariots gave the Assyrians much of their military power.

Barbarian Europe

Europe was not as well suited to the chariot. With its uneven terrain and thick forests, it lacked the open spaces that made the chariot so useful.

Chariots caught on as a prestigious way of traveling. The Iliad features accounts of Greek heroes riding to war in chariots then dismounting before fighting.

As far away as Britain, nobles rode chariots. The Romans watched them showing off their athleticism by running along the yoke before flinging javelins at their enemies – an impressive but militarily ineffective feat.

By then the chariot had gone into decline. Apart from these island barbarians, almost no-one in the West was using it in battle. A different form of soldiering had taken its place.

The Triumph of Cavalry

The chariot was doomed by the same thing that allowed it to excel – horse breeding. Stronger horses could carry men on their backs into battle. Cavalry were more maneuverable than chariots, more flexible, and a more efficient use of manpower. Instead of two horses pulling one driver and one archer, two horses could carry two archers or two men running the enemy down with swords and lances.

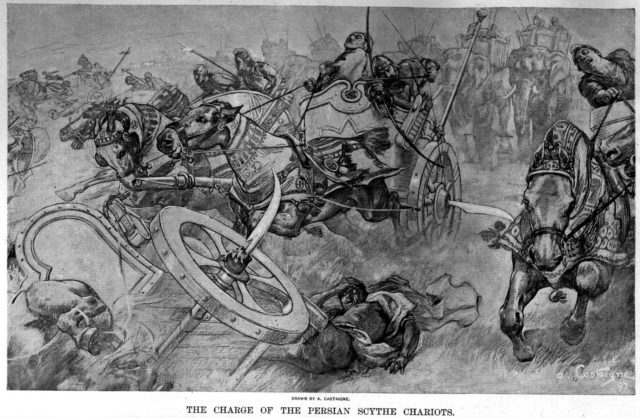

Stronger horses made chariots more effective, but they also made them obsolete. By the time the Romans rose to power, they were using them only for sports and parades. Cavalry had taken their place in war.