Weather played an important role in World War II

Germany was far behind the Allies

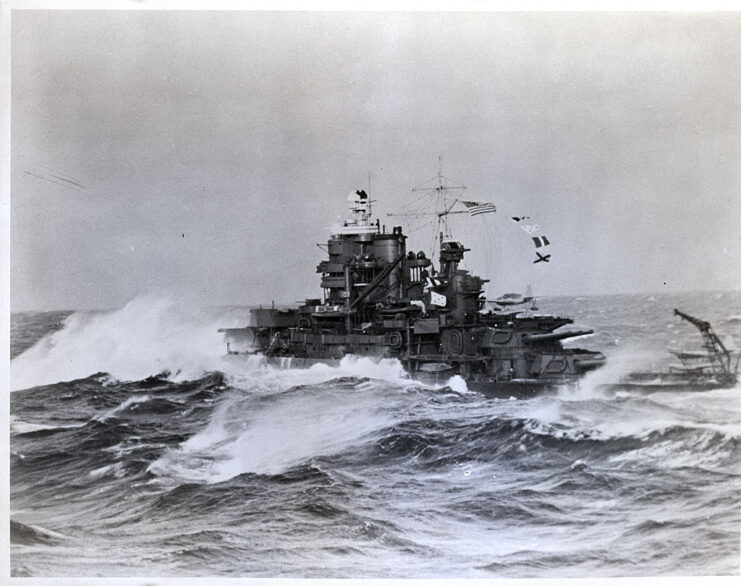

Lagging behind the Allies in gathering crucial weather intelligence, the Germans turned to risky alternatives. They deployed used specially-modified aircraft, naval ships, and even U-boats in daring missions to collect meteorological data. But these efforts often ended in failure—lone weather ships were vulnerable targets for Allied forces, and aircraft had limited range and effectiveness for such specialized tasks.

Realizing they needed a more reliable solution to close the gap, the German military devised an audacious plan: establish their own weather stations on North American soil. This led to the development of the Wetter-Funkgerät Land (WFL)—a covert, automated weather station designed for enemy territory.

Wetter-Funkgerät Land

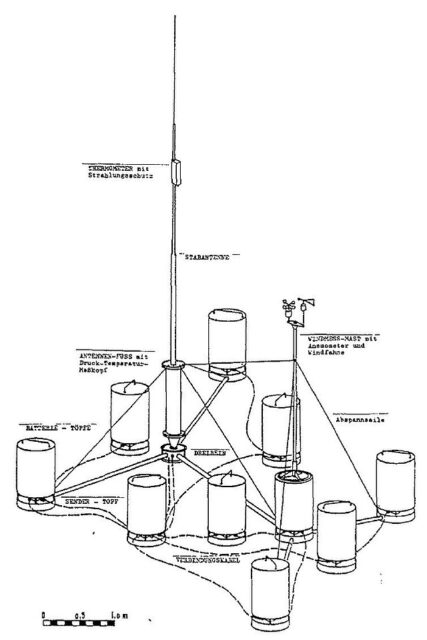

Scientists at Siemens developed an automatic weather station capable of transmitting data every three hours via radio waves on 3940 kHz. Known as the Wetter-Funkgerät Land, twenty-six were manufactured; 14 were placed in Arctic and sub-Arctic regions, including Allied-occupied Greenland, and five were stationed around the Barents Sea. Two were designated for North America.

The WFL featured an array of specialized instruments, including two masts. One of these masts held the anemometer, which measured wind speed and direction. It also included a telemetry device that automatically recorded data and transmitted it via a radio signal. Powered by rechargeable nickel-cadmium batteries, it could operate for up to six months.

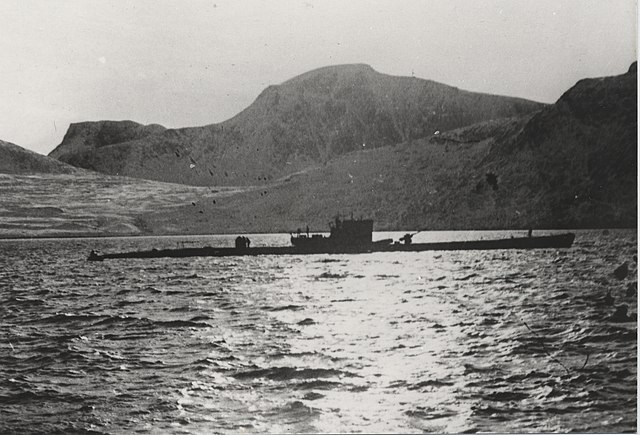

Two U-boats were assigned to install the automatic weather stations in North America. U-537 was the first and only one to successfully deploy the WFL, codenamed “Kurt.” The second, U-867, was sunk in 1944 near the Norwegian coast by a Royal Air Force (RAF) bomber.

Installing the Wetter-Funkgerät Land on North American soil

Camouflaging Weather Station Kurt

Weather Station Kurt was cleverly disguised to avoid detection. The Germans labeled the equipment with the logo and name of a fictitious group—the “Canadian Meteor Service”—and even littered the area with empty American cigarette packs to give the illusion that Allied forces had installed it. At the time, most civilians had limited knowledge of military operations, and German intelligence believed that lower-ranking Allied troops, if they stumbled upon the station, would likely overlook it to avoid drawing attention.

The submarine U-537, which deployed the station, spent less than 30 hours on the coast of Newfoundland before beginning its return journey. During the voyage home, the sub was attacked three times near the Grand Banks by Canadian aircraft. Despite the dangers, the U-boat survived each encounter and made it back to the port of Lorient in German-occupied France on December 8, 1943—70 days after its mission began. Though U-537 didn’t claim any Allied vessels on that patrol, the mission marked a rare instance of German activity on North American soil.

Becoming a forgotten part of World War II-era history

Weather Station Kurt only worked for a few weeks before failing, and it remained undiscovered long after World War II was over. In 1977, geomorphologist Peter Johnson was conducting research near Martin Bay when he stumbled upon the site. He thought it was a Canadian military outpost and simply marked it as “Martin Bay 7” on the map he kept during his research.

Around that same time, a retired Siemens engineer named Franz Selinger was writing a history of the company. He went through Kurt Sommermeyer’s papers and learned of the station’s existence. He subsequently notified the Canadian Ministry of Defence.

More from us: The Devastating Invasion That Kicked Off the Second World War

In 1981, Weather Station Kurt was officially discovered, standing on the same spot where the Germans had left it over 30 years prior. It was dismantled and taken to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, Ontario, where it remains on display to this day.