The 2014 movie The Imitation Game opened up the secret world of cryptanalysis – the art of breaking codes.

Codes and ciphers have been used in warfare for centuries. One of the best known early examples was the Caesar Cypher. This was a system of letter substitution used by Julius Caesar to encode sensitive military messages. It was a fairly simple system by today’s standard and would not have been difficult to decode.

Cryptography was used throughout the medieval and renaissance periods although more for political intrigues than warfare. It was not until the 19th Century that it became more significant.

An important breakthrough was the work of Charles Babbage, an English Mathematician. Babbage is more famous for inventing the principles of modern computing. But his work during the Crimean War led him to break the Vigenère cipher, a 16th Century code that, until then, had remained a mystery.

The 20th Century brought new ways of transmitting information over long distances, and code breaking soon became a major part of military strategy. During World War Two, both sides relied on codes and their code breakers for communication and intelligence gathering.

Britain

The center of codebreaking for the Allies was at Bletchley Park in England. Run by the British Intelligence, this top secret base was located in a 19th-century mansion in the English countryside which housed specialist equipment.

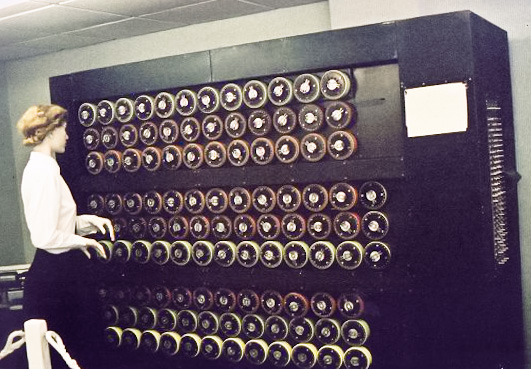

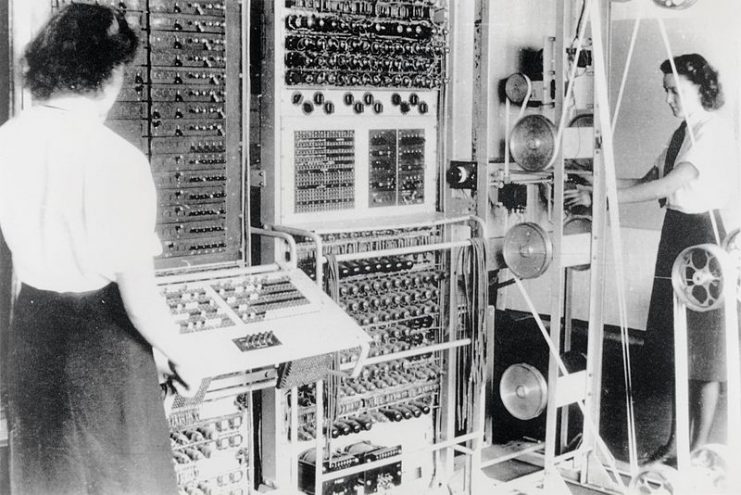

Bletchley Park attracted some of the best minds, bringing together people who would apply themselves to the important work of code breaking. Both men and women were employed although the importance of the work done by women has only recently been recognized.

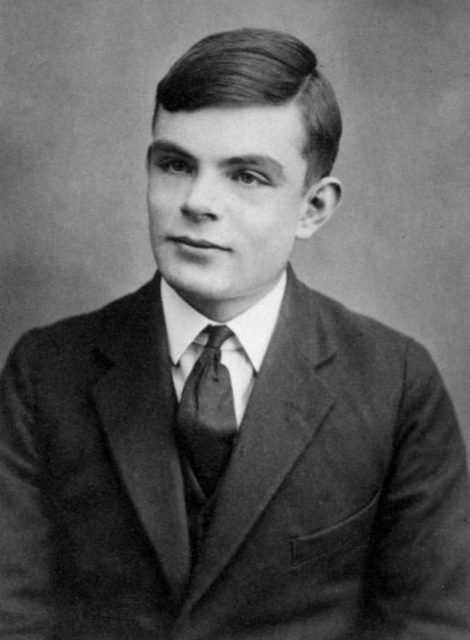

Alan Turing

The name which first comes to mind when we talk about code breaking is Alan Turing.

Turing was a mathematician and a graduate of both Cambridge and Princeton Universities. In 1939, he joined the staff at Bletchley Park as a cryptanalyst. There he turned his great analytical and logical skills to the task of deciphering German codes.

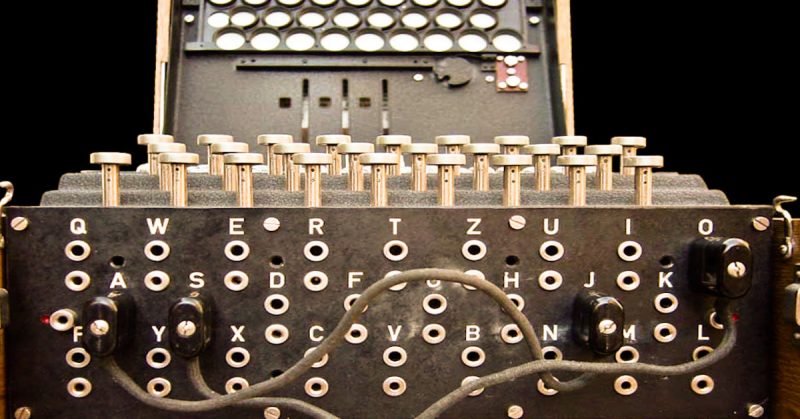

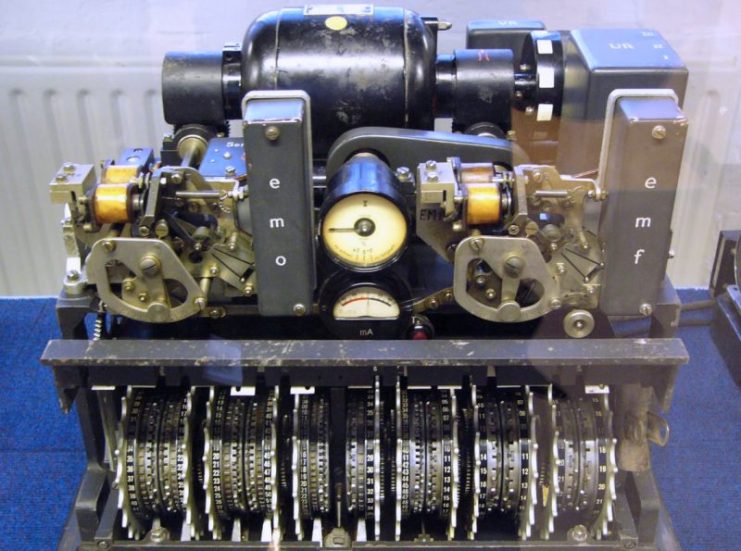

He is credited with breaking the Enigma code in 1941. The Enigma code was Germany’s most important code, and they believed it was unbreakable. The device that produced the code was known as the Enigma machine. Fortunately for the British, they managed to capture a machine in 1941 making it easier to break the code.

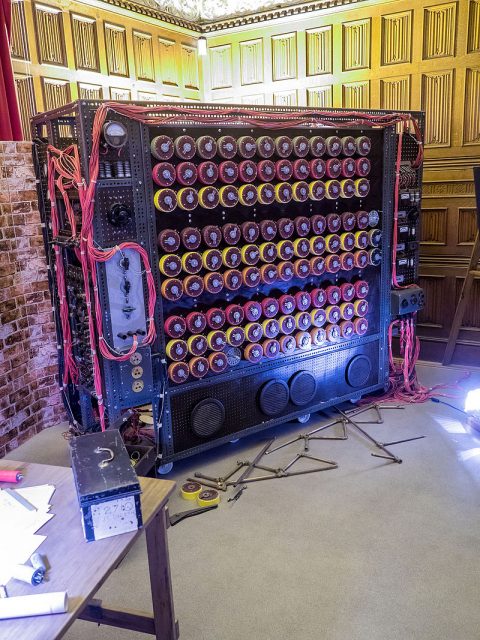

Turing developed a British “Bombe,” an electronic device which was used to break the Enigma code. The Bombe was a type of early specialized computer.

After the war, Turing built on these ideas to develop something closer to the computer we recognize today. Turing’s life and tragic end by suicide following years of persecution and “treatment” for his homosexuality were immortalized in the 2014 film The Imitation Game.

William Thomas Tutte

Less well known but also very important was William Thomas Tutte. Throughout the war, the Germans used a number of complex codes for communication. One of these was the Lorenz cipher. This was a stream of code produced by the Lorenz cipher machine which allowed the Germans to communicate safely by radio.

Bill Tutte, as he was known, was born in England in 1917. He had originally studied chemistry at Cambridge before switching to mathematics in 1940. Soon after he began working as a cryptanalyst at Bletchley Park.

It is hard to imagine today, but at that time Tutte had to work everything out by hand. He would write down streams of code which he and his colleagues then studied in search of patterns that would give them a clue to the meaning.

One of the difficulties with the Lorenz cipher was that the British did not manage to get hold of a Lorenz cipher machine. All the work had to be done by analyzing intercepted coded messages.

Germany

Less is known of the German codebreakers. Much of this kind of work was carried out across different departments, so there was no equivalent of Bletchley Park.

As a result, they were less effective than the Allies because people were working separately from each other and not sharing the results. They did, however, have some success in breaking both British and US Naval codes.

One of the notable German cryptanalysts was Wilhelm Tranow who worked in the Cipher Department of the High Command of the Wehrmacht.

Tranow’s career in code breaking began before during the First World War as a radio engineer. By the outbreak of the Second World War, he was working for the German Navy’s monitoring service. He is credited with breaking the Naval Cipher and Naval Codes used by the British Admiralty.

Poland

Marian Rejewski

Shortly after the invasion of Poland by Germany in 1939, a group of cryptanalysts were evacuated to France. The group consisted of employees from the Polish Cipher Bureau who had been working on the German Enigma code. Among these was Marian Rejewski, a mathematician who had attended a secret course in cryptology after university.

Rejewski’s work on the enigma code was very significant. As early as 1932, while still in Poland, he developed an in-depth understanding of how the machine worked. He even managed to reconstruct its internal wiring without ever having seen the machine.

Rejewski is credited with doing groundbreaking work that allowed the code finally to be broken by Turing in 1941.

Rejewski returned to Poland after the war. For a long time, he kept quiet about his remarkable code breaking skills to avoid the government becoming interested in him.

Photo courtesy of Janina Sylwestrzak, Rejewski’s daughter, CC BY-SA 2.5.

America

Once the US entered the war in 1942, they also contributed to the effort of code breaking and did a lot of important work on Japanese ciphers.

One of the features of American cryptography is that many of the top code breakers were women. The American military actively recruited from women’s colleges. This may have been because, despite the high level of skills involved, they considered code breaking to be rather like secretarial work. This made it suitable work for women.

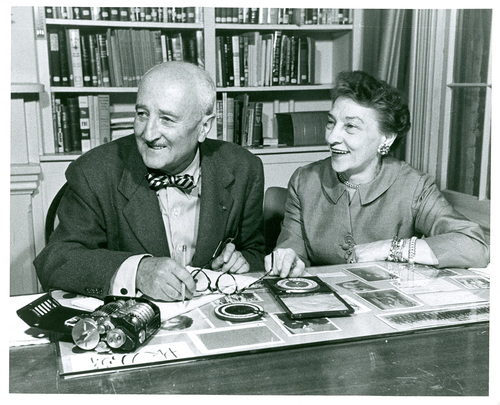

One of the most successful American cryptanalysts was Elizabeth Smith Friedman. Born in Indiana in 1892, her career as a cryptanalyst did not start as you might expect. She studied English Literature at college, and her first experience of cryptanalysis was decoding messages hidden in the works of William Shakespeare.

In 1916, Friedman joined Riverbank Laboratories where she had the first chance to study cryptanalysis formally. At first, she used her skills to decode messages sent during the prohibition era by alcohol smugglers or “rumrunners.”

During World War 2, she worked for the FBI and the Office of the Coordinator of Information which was a forerunner of the CIA. There she applied her skills to counter-espionage work. This included helped to break up a network of Nazi spies trying to encourage unrest in South America.

She also decoded messages in correspondence from Velvalee Dickinson, a notorious spy. Dickson was later charged with passing information about the US Navy to the Japanese.

Late recognition

Due to the secretive nature of their work, many cryptanalysts never received recognition for their work until many years later. But their contribution to the war effort was hugely significant.

Some even credit Britain’s cracking the Enigma code with bringing the war to an end as much as two years early. When you consider how much human suffering this must have saved, you can understand the importance of the work of the code breakers.