Typically, prisoners of war who plot an escape worry most about being captured and forced back into captivity. The idea of breaking free only to willingly return sounds almost absurd. Nevertheless, in 1943, three Italian POWs did just that—after scaling Africa’s second-tallest peak.

An escape (and return) plan is hatched

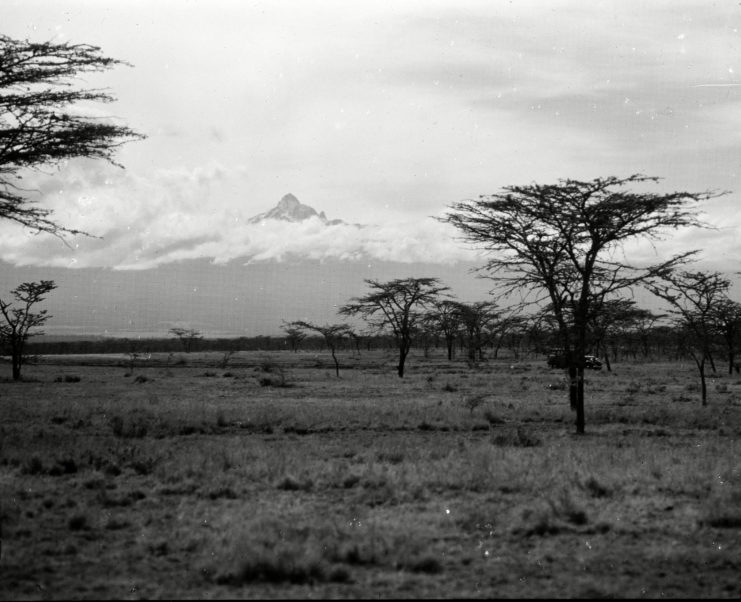

By 1942, Italian POW Felice Benuzzi was a prisoner at Camp 354, near Nanyuki, Kenya. Conditions at the camp were not terrible, but Benuzzi was extremely bored. One day, he caught a glimpse of Mount Kenya through the clouds. From that moment on, he knew he had to climb that mountain.

Felice Benuzzi was born in Vienna, Austria on November 16, 1910. He grew up in Trieste, mountaineering the Julian Alps and the Dolomites. In 1938, after studying law at the University of Rome, Benuzzi decided to enter into the Italian Colonial Service and was sent to Ethiopia as a colonial officer. He was stationed in Ethiopia’s capital city, Addis Ababa, when a British Army offensive moved into East Africa. He was interned at British POW Camp 354 in 1941.

Although Benuzzi was a mountaineer, Mount Kenya was the first 17,000-foot peak he’d ever seen. He later wrote about how he remained “spell-bound” for hours after seeing it, adding, “I had definitely fallen in love.”

Supplies are gathered

Slowly but surely, Benuzzi came up with a plan of action. Because he was in a POW camp, he had minimal resources for his climb. He wrote to his family in Italy, asking them to send his boots and warm, woollen clothing. He stopped smoking and was able to barter with his extra cigarettes to get his hands on other necessary items.

Benuzzi also scoured camp trash for usable items and hoarded crackers, chocolate and dried fruit from packages he received. He also used hammers stolen from the camp workshop to create ice picks, and made his crampons from bits salvaged from trash heaps. For maps, Benuzzi only had the drawings he had made of the mountain and a label from a food can.

The mountaineer realized he needed to recruit other prisoners to join him. The first individual he approached was his bunkmate, Giovanni “Giuàn” Balletto, who was a doctor and fellow mountaineer. The second was a man named Vincenzo “Enzo” Barsotti, who had never once climbed a mountain. However, he was recruited because he was thought to be “mad as a hatter,” and “mad” people were what was needed.

Now that Benuzzi had his team and supplies, the only thing left to do was figure out how to escape the camp. Balletto had been given a small plot of land in the camp garden, where he grew tomatoes and other vegetables. He had built a small tool shed on this parcel of land, where the three climbers gradually started to move equipment and supplies.

Access to the garden was through a locked gate that was open to prisoners displaying a garden pass. Only Balletto had a pass, and the men would need to move through this gate at night. What they really needed for their escape was the key to the garden gate.

They tried to get ahold of the key several times. One fateful day, Benuzzi stumbled upon it carelessly left on the compound officer’s desk. He was able to make several impressions of it in a piece of tar and had a prisoner mechanic cut the key based on the impressions. The team tried to unlock the gate with their new key, but, much to their dismay, it didn’t work. Finally, after making many adjustments and oiling the key, the team successfully unlocked the gate.

Their breakout was scheduled for January 24, 1943.

A great escape, followed by a return to camp

On the night they slipped away, the three prisoners managed to cross the garden and exit the camp unnoticed. But reaching Mount Kenya was still a long journey ahead. For several days, they moved under the cover of darkness—and eventually in daylight as well—trekking through dense tropical forests at the mountain’s base until they finally arrived at its northwestern ridge.

Against all odds, the trio began their ascent of Mount Kenya, establishing a makeshift basecamp at 14,000 feet. Benuzzi and Balletto set their sights on Batian Peak, the mountain’s highest summit, but a sudden snowstorm forced them back to camp, exhausted and freezing. After a day of rest, they refused to give up and instead turned to Point Lenana, the third-highest peak, rising to 16,355 feet.

Amazingly, the two men reached the summit. There, with numb fingers, they planted a homemade Italian flag and sealed a handwritten note inside a bottle—proof of their impossible feat. Victorious, they descended to rejoin Barsotti at basecamp, before all three began the long trek back down the mountain.

The three Italian POWs returned to Camp 354 eighteen days after their escape. After returning, they were sentenced to 28 days in solitary confinement. However, their sentence was reduced to only seven days, as the camp commandant was impressed by their “sporting effort.”

More from us: Here’s The Way German Commandos Rescued An Imprisoned Bentio Mussolini

In 1946, Benuzzi returned to Italy. He later published a book about the 1943 climb, titled No Picnic on Mount Kenya. He passed away in Rome in July 1988.