Nazi Germany perverted every democratic institution that was supposed to uphold the rule of law and ensure the people of Europe’s most powerful nation were governed fairly. And in relation to the law, Roland Freisler played a huge part in this warped ideology.

Freisler displayed a strong patriotic streak towards his country from a young age. He was awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class and 2nd Class because of his actions with the German Imperial Army’s 22nd Division during the First World War.

It was during this action that the lawyer was captured by the Russian forces and interred in a prison camp in 1918. It was then that Freisler learned Russian and was appointed a Commissar and given the duty of organising the camp’s food supplies.

This title, handed to him by the communists, that would prevent Freisler from advancing further in the Nazi party as it tainted his reputation and made him appear to be someone who had co-operated with the Soviets.

Freisler’s action during the Great War interrupted his law studies and after the conflict had ended the lawyer returned to the University of Jena and was awarded a Doctorate of the Law in 1922.

Within four years he would use his legal knowledge for immoral ends and ended up defending Nazi party members in court after he joined the party in 1925.

Despite being thought unsuitable for authority by members of the Nazi party, he nevertheless caught the eye of the bigwigs, thanks to his performances in court. Freisler was appointed as the Director of the Prussian Ministry of Justice in 1933, followed by stints as Secretary of State in the Prussian Ministry of Justice (1933-1934) and the Reich Ministry of Justice (1934-1942).

This evil advocate of National Socialism quickly became one of the most feared judges in all the land, thanks to a combination of his excellent legal knowledge, berating and aggressive delivery and humiliation tactics in the courtroom.

Freisler would think nothing of denying a defendant braces and a belt, and then condemning them for not being able to keep their trousers up during the trial. He would also think nothing of sending children to their death, or plotting the genocidal destruction of the entire Jewish population of Europe.

Despite this fervent and wide-eyed commitment to Hitler and his ideology, Freisler was never promoted to a post beyond the judiciary.

There are a number of theories surrounding why this was: one idea suggested Freisler lacked the backing of anyone in a senior position within the party – another says his past association with communism prevented any further progression.

But the judge never lets this cloud the tyrannical way he policed the People’s Court, to which he was promoted to the role of President in 1942.

This was a separate administrative system beyond the reach of the regular judicial system and being brought before it under Freisler was tantamount to a death sentence. 90% of cases brought to the court by the judge resulted in death or a life of imprisonment.

In fact, Freisler succeeded in turning the court into a psychological weapon and a way to control the citizenry of Nazi Germany. He also had the dubious honour of being the man who introduced the death penalty for juveniles for the first time in his county’s history.

The trials that he held have been described as an executive execution arm of the state, with Freisler as the gleeful judge, jury and executioner. He even took the court records and peppered them with as much Nazi terminology as possible to lend the verdicts some form of twisted legitimacy.

Between 1942 and 1945 Freisler put to death 5,000 people – in three years he put as many defendants in front of the executioner as the People’s Court had done in the years 1934-1945. He even sent the family of Joseph Muller, a Catholic priest, the bill for his execution by guillotine.

Acts like that show the cold-blooded nature of the man, and also the vim and vigour which he brought to his role in the People’s Court – which had become a byword for show trials and vicious sentences,

Perhaps because of this, Freisler was thought important enough to be invited to the 1942 Wannsee Conference, which sought to deal with the ‘final solution’ for the Jewish race throughout Europe.

As a judge, this Nazi was a force to be reckoned with. He spoke with such ferocity, often brow-beating and shouting down those who had been brought before him. Freisler was clearly a devoted follower of Hitler and of his ideology – something that is reflected in the charges of those brought before him.

Most of these were for ‘defeatism’, or for selling items on the black market and for work slowdowns. These crimes came under the broad brush of the term “political offences,” and most were dealt with harshly by the raving judge.

Freisler was the judge who oversaw many high-profile cases, including that of the White Rose group, who had been captured by the Gestapo. The organisation was non-violent, but met a bloody death when the ring leaders were beheaded by guillotine in 1943.

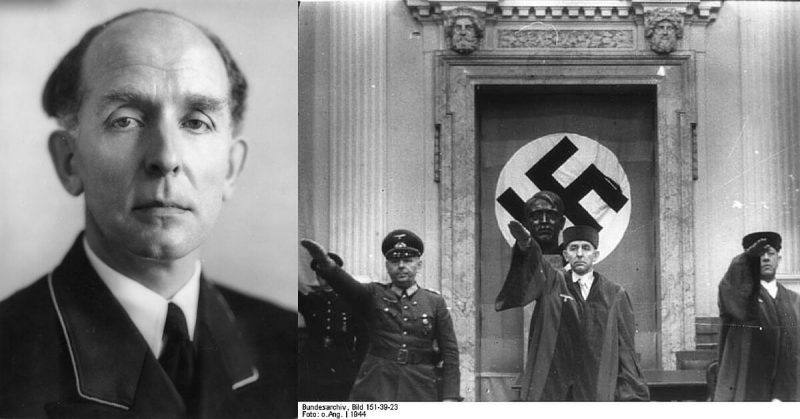

One of his most documented moments was during the 1944 show trials of the group who had plotted to assassinate Hitler. The trial was documented so it could be used as propaganda, and the film showed Freisler clinically interrogating the defendants, before descending into hyperbolic abuse and mental degradation.

Nearly all of those brought before him during that trial were hanged, many within two hours of a sentence being proclaimed.

The judge would meet his death while the war still raged around him, in a bombing raid on Berlin during 1945. It was a Saturday, and Freisler was presiding over a session of the People’s Court when an American air raid caught them unawares.

The court was swiftly evacuated, but Freisler ran back into the building to retrieve some documents he thought were important to the farcical trials he conducted. It was at this moment that a bomb struck, and the judge was crushed to death beneath a falling piece of masonry.